Tara Jane O’Neil has been working as a multi-instrumentalist, visual artist, audio engineer, and composer for three decades, but during the pandemic, she still found herself wondering if she was a musician. “What makes that true,” she asked herself. “Shows? Inspirations? Deadlines?” Despite a long and vast career as a working interdisciplinary artist, O’Neil still feels like she’s “somehow getting away with something.” What is certain is that, in 1993, she quit a job so she could go on tour, and that felt like it signified the acceptance of her trajectory.

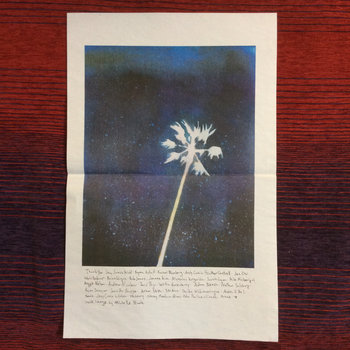

O’Neil’s work as a visual artist and as a musician has always been simultaneous and interconnected, emerging as self-directed expressions of adolescence: ways of coping through creation and exploring her curiosities. An outgrowth of this combinative artistic practice is that O’Neil has created the art for most of her releases, the images usually coming to her once the music is done. “Looking at them, it seems like they are self-portraits,” she says. O’Neil has also contributed art to other artists’s album covers; to publications such as Wire, Magnet, Venus Zine, and Punk Planet; and to the covers of poetry books by Cynthia Nelson and Maggie Nelson.

Though guitar was O’Neil’s first instrument of choice, bass was her first band instrument. While teaching herself bass in her Louisville room to Jefferson Airplane records, future bandmate Jason Noble (Shipping News, Rachel’s) pulled her out to play and sing with him and Jeff Mueller (Shipping News, June of 44) in her first band, Rodan. Existing in a pioneering space somewhere between post-rock and post-hardcore, O’Neil says “Rodan had a lot of fun playing super composed parts, but also a lot of fun improvising where we could, before songs and during a couple of songs. Wherever there was space to stretch out, we did that. Sometimes we would throw in a ‘cover’ that none of us knew how to play, so we improvised those.” O’Neil’s musical approach since has remained deeply intuitive and improvisational—though “not classic improvisational technique or study,” she clarifies; her practice was honed watching and listening to other musicians, playing along with records, and playing along with others in a live capacity.

Rodan was relatively short-lived, but they managed to set all participants up for continued success as musicians in many projects. They also captured the spirit of the time well in the indie cult film Half-Cocked (1994), in which O’Neil and the other members of Rodan starred as the fictional band Truckstop, documenting Louisville’s legendary old Victorian mansion-turned-indie-music-hub Rocket House and the larger U.S. indie rock underground via its cast of auxiliary characters from many regional scenes. Half-Cocked was shot “just before the Rodan record came out and our little scene in Louisville was also starting to take off in its own way,” O’Neil says. “It definitely captured some of the last moments of a moment there and I am glad it exists. It was also a fictionalized portrait of our thing, which by the time of its release, no longer existed. The primary cast on the cover photo features five of us who were really tight friends and two of us [Jason Noble and Jon Cook] are no longer living on Earth and that alone makes for a conflicted feeling.”

Between 1994 and 2002, O’Neil bounced back and forth between Louisville and New York City, where she played with Cynthia Nelson in Retsin; founded the Sonora Pine with Sean Meadows (June of 44, Lungfish), Samara Lubelski, and Kevin Coultas (Rodan); and also joined the indie country-rock outfit the Naysayer in 2000. She went on to the Pacific Northwest in 2003, becoming enmeshed in the regional scene there; collaborating with K Records artists like Mirah; Portland counterculture philosopher and performance artist Fred Nemo; and making “intense math-metal figures” with Rachel Carns (Kicking Giant, The Need) and Ted Kwo in Portland’s King Cobra, before becoming largely focused on her own solo career and spending much of the following decade on tour. “I think in those mid-2000s, I was psyched to have some other visual element and other energy on stage with me. Fred Nemo doing wild shit while I played quiet songs and loud noise really enhanced my experience—maybe it confused others, but you know, I am still a punk and so that’s great,” O’Neil says.

Since 2011, O’Neil has lived in Southern California, continuing to work on her solo material while also working as a hired gun for other artists. This includes working as a session player for Steve Gunn, Come, Amy Ray, (Indigo Girls), Hand Habits, Papa M, Mount Eerie, Mirah, Ida, Lower Dens, and many others, as well as collaborating with Marisa Anderson. Recently, dance works have become a focus via “Bass and Body Duo” performances with her wife, dancer and designer Jmy James Kidd. Since 2012, they have been exploring ideas of “somatic listening,” developing a body of work which encourages the creation of complementary vibrational parallels through the combinatory power of music, dance, and live energy. A collection of these instrumental pieces made in collaboration with Kidd’s choreography entitled Music for Movement is coming soon. “I like to play and experiment, always, and inside a dance context I am encouraged to be expressive in whatever way and that’s provided a really great balance for me as a person while I make other very composed music,” says O’Neil. “Through working with Jmy, I’ve been able to stretch out musically in ways that don’t fit into a rock club or even inside the Tara Jane O’Neil thing.”

Another factor in her move towards more experimental performances is O’Neil’s strong feeling that live music is a social form. “I hate it when it becomes voyeuristic, I hate to feel isolated, on a stage, in front of people,” she says. “If we are gathered together, I want to be together, in some way. I think after so many solo shows and tours I came to realize how separated performer and audience can become. The music I make is intimate and it is an invitation; it only works if there is attention and I try to give back into that shared space.”

Additionally, O’Neil is not interested in being a “reproduction device.” She believes music is a living thing, so any improvisational twist or entrance she can find, she takes to acknowledge the present inherent in the making of sound. This has driven the development of things like the Ecstatic Tambourine Orchestra, a body of percussionists re-created each time O’Neil hands out the large collection of tambourines and bells she has gathered and carried with her around the world, tossing them into the crowd near the end of the set and starting a pulse with her own tambourine for audience members to build on. “I wrote the song ‘Dig In’ like this and played it a hundred times with a hundred different Ecstatic Tambourine Orchestras,” she says.

In addition to playing all of the instruments on the majority of her solo records, O’Neil also engineers her own recordings, as well as those of friends and acquaintances on occasion. “In the very early ‘90s, everyone had a 4-track and so that was a gateway,” O’Neil explains. “It was and still is possible to make a decent sounding recording with a multi-track cassette player. I wasn’t very good at it, but using those gave me some rudiments. So, in a way, it was just part of all the learning I was graced with in my late teens and early 20s. My early bands and my early songs were crafted on recording machines and swapped with bandmates and friends. So, it was an instrumental part of making music as well as community—and community was the only way we got things done.” While O’Neil learned some “real” stuff when she ended up in “real” studios, that wasn’t very often.

“Without budget or backup, it’s a good idea to become self-sufficient somehow,” she says. “I was able to record so many records with my basic gear that I would not have been able to afford to make at a pro studio. Necessity affords so many things.”

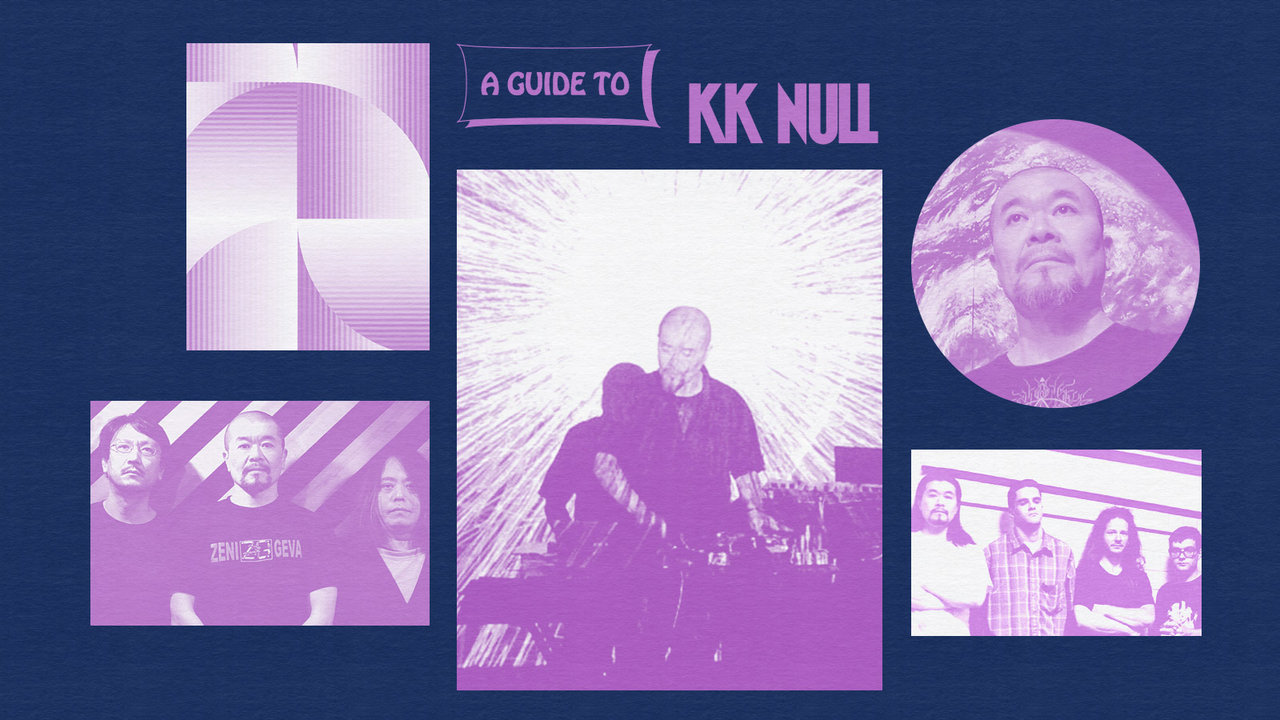

Here are 14 releases illuminating both Tara Jane O’Neil’s singular, elemental style and her astounding—but deeply humble—interdisciplinary genius.

Rodan

Rusty

Rodan is one of those short-lived bands whose influence lives on eternally, not just via all of the incredible bands its members went on to form, but through all of the people they inspired to start their own bands. While comparisons to Slint’s Spiderland are unavoidable, there is a haunting beauty to these songs despite their heaviness, mathiness, and the extreme dynamic shifts which makes it ultimately less likely that people will ask you to turn it off. People familiar with O’Neil’s more elemental, folky offerings may be surprised to know she played bass in a post-hardcore band responsible for songs like “Shiner,” but slower, more ruminative tracks like “Bible Silver Corner” make it clear that this band is indeed the origin of the beautiful mystery O’Neil has spent three decades investigating in her solo work and that she has always been a deeply experimental sonic communicator.

Rodan played with three different drummers in their two years of existence between 1992 and 1994, and at this point in time there are three albums demonstrating the different offerings of each. This album is named after its primary audio engineer, Bob “Rusty” Weston (Shellac, Volcano Suns).

The Sonora Pine

II

The Sonora Pine began when O’Neil and Sean Meadows were both recent New York City transplants from the mid-South in late 1994. “We were broke and we had a lot of music to play, so that’s how he and I spent time,” O’Neil explains. “Two years later, Sean was touring heavily with June of 44 and Lungfish and I was doing lots of solo writing.” As a result, the second album features just Samara Lubelski, Kevin Coultas, and O’Neil. Unlike the Sonora Pine’s more widely listened-to debut album, II disappeared from sight soon after its release because the band broke up.

“Kevin and I were recording with the basic equipment we could gather and decided that we would handle the engineering and mixing ourselves. He did most of it. The basic tracking happened in a beautiful old camelback shotgun [house] in Louisville, which is now a popular egg restaurant,” O’Neil recalls. “With the exception of ‘Linda Jo,’ which was written by Kevin, I remember that the writing of this album felt a lot like how it felt to write the next five solo records: a very interior experience, but the resulting music destined for finding other players to make it work in a live scenario. Lots of parts and arrangements written for an ensemble. I think this album was the beginning of my ‘solo’ career, but it took another decade for me to figure out how to write music that could live when rendered by me, truly solo.”

O’Neil says there will be news regarding this classic release and to look to the skies in early fall 2022.

Tara Jane O’Neil

Demos and Rarities from Peregrine

A companion album to O’Neil’s debut solo album Peregrine, this compilation of demos and rarities provides insight into the time before cell phones when artists were more likely to carry around notebooks, sketchbooks, and tape recorders for catching ideas while out in the world. “This collection is a spastic smattering of tapes I found that contain not only me writing the record Peregrine, but figuring out how to play all the parts by repeating one part ad nauseam, so I could play over its playback and then record the new part on its own. A tedious process,” O’Neil remembers. Also captured are some sounds of that time when she was back and forth a lot between NYC and Louisville, from 1994 to 2000. “We hear Michael Hurley ask to be on the list and we hear Eileen Myles agree to me using a line of hers in a song. We hear the Clinton impeachment vote and we hear a lot of my friends,” she says.

In The Sun Lines

O’Neil began writing this album in upstate New York in the summer of 2001, where she lived for six months, but it carried over when she and Cynthia Nelson moved back to Louisville. There she once again had space in a beautiful and haunted old brick building and life slowed down considerably. “I think it pairs well with Peregrine, though its energetic and sonic hue is unique,” O’Neil says.

She was also “in the throes of a simmering chronic illness, and this album was a lot about moving from a big city pitch to a more individual and slow daily reality,” she says. “I woke up really early most days and went to the studio to make these recordings: a measured and regular process. For this album, I was playing with stretching out the basic guitar compositions and fooling around with improvising with myself while overdubbing. I wanted a live feel even on the tracks in which I played most of everything.” On this release, she is joined by many of her very gifted friends, like Rachel Grimes (Rachel’s), Ray Rizzo, and Dan Littleton (Ida). During this same season, she made the improvised guitar album Music For A Meteor Shower with Littleton.

After this album, O’Neil moved to the West Coast and examined how she could make more “movable” music as she spent much of the next nine years on tour.

You Sound, Reflect

O’Neil thinks that with You Sound, Reflect, she was perhaps making a record that she wanted to hear. What she remembers most about its 2004 release was the way that “online music outlets were really coming on around that time. “I remember being able to read a review by a woman that asked who I thought I was,” O’Neil recalls. “I guess that meant she liked it on some level and just couldn’t let me do those things. It was a real shift in reality, seeing things on the internet like fast boomerangs.”

“Famous Yellow Belly,” a re-write of Leonard Cohen’s “Famous Blue Raincoat,” showcases O’Neil’s ability to create rhythms experimentally with the clicking track and whirring sounds, and songs like “Without Push” bring in violin from Nora Danielson (The Intima) and prove that O’Neil belongs as much among the ranks of experimental composers as among those of rural Midwestern poet-philosophers like Jason Molina and Will Oldham. The album cover, showing O’Neil’s face divided between sunlight and shade, feels a perfect depiction of what her music is: something that washes over you, shifting like the sun between clouds or various earthy obstacles.

In Circles

On In Circles, O’Neil says she was “really working out some deep spirit and string waters.” Composed while she was doing enormous amounts of solo touring, the result is a very guitar-centered record. “I’ve always loved arranging for other instruments, but for this I really just played around with guitar and the sonic bedding I could make for it with very rudimentary processing,” O’Neil explains. “Quite interior.” Possibly the greatest artifact of this period of her career, in which her aesthetic of combining tape loops and other electronic effects seamlessly into folk music is on full display, In Circles is serious evidence that O’Neil is one of the most important songwriters to grace the continually shifting outer limits of popular music.

Wings. Strings. Meridians

This compilation of drawings and paintings and music came from Mike McGonigal and Steve Connelly’s Yeti imprint. O’Neil was really happy they asked her to make an art book. At that time, she was doing lots of drawings to sell on tour or online or show at galleries. “It’s cool to have the efforts of those few years in a lookbook,” O’Neil says. “The CD that came with it was a lot of process and demo stuff,” including some film scores and live tracks from Istanbul, Paris, and Long Beach. “I really like the ephemera from other artists, their sketches, and discarded lyrics and live iterations—maybe I’ll share another batch soon,” she says.

O’Neil also published the book Who Takes a Feather? on Map Press of Japan in 2004.

A Ways Away (2019 Deluxe Artist Reissue)

Compact Disc (CD), Cassette

Half of this album was tracked with Christina Files (Swirlies, Syrup USA, Victory at Sea). O’Neil, who hadn’t gone into a studio for a few years, composed much of the record while touring. It felt like it needed to be captured in a live scenario. “I like the songs on this record a lot,” O’Neil says. “Feels like a fully realized attempt at making a sonic bed for a song to live in.” O’Neil included the single and a couple other things that didn’t make it on the record the first time for a deluxe artist reissue. This album is a great fusion of the live TJO experience and her enormous capabilities in the studio, and it includes guest appearances from many talented individuals: Jana Hunter, Mirah, Osa Atoe (New Bloods), Geoff Soule, Bob Jones, Jean Cook, and Daniel Littleton. The studio ensemble of the Ecstatic Tambourine Orchestra even included Sara Lund (Unwound).

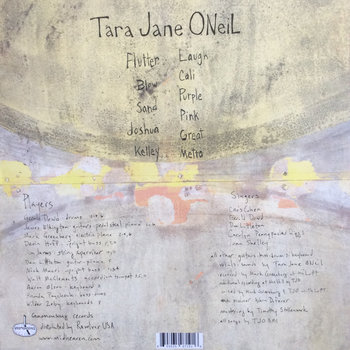

Where Shine New Lights

Compact Disc (CD), Vinyl LP

This release for the legendary Kranky label is the culmination of something O’Neil had been working towards for a very long time. “It is mournful, but it is hopeful and full of love and the elements of life as I understand them,” O’Neil says. “I’m always changing shape and direction, but I’d been chasing down this dog for a few years and I think I got it. I don’t rank my records, but I’ll rank this as a really, really good one. I made this during a period where several friends died, and it’s elegiac in its way. It’s an entrance.”

While O’Neil is an enormously talented lyricist, exemplified here on “Elemental Finding,” much of the vocalizing on this record is wordless, more purely emotive than it is verbally discernible. It is music for departures, which are also always arrivals, operating in that threshold space where many of our most indescribable experiences occur, so it feels perfectly suited to its task and a definite height in her creative powers. As a meditation on the cycle of life, it captures very well and rather gorgeously the movement into and out of consciousness.

Tara Jane O’Neil and Kazumi Nikaido

Compact Disc (CD)

Japan became a significant part of O’Neil’s creative life thanks to her friend Norio Fukuda, who reached out to her in late 2001. “I went there for the first time in 2002 and have returned for so many tours. He is the guy who releases my records and arranges art shows and very special happenings over there. It’s really lucky that some people got into what I do there, but it’s really all about Norio’s hard work. The first few tours were part me making music, part me struggling to make that music and getting electrocuted and flailing in any number of cross-cultural ways. I’m grateful for the community I’ve had there and can’t wait to go back.”

This collaboration was a very fun process for O’Neil. It began in Kyoto in 2008 and concluded in Kobe in 2010. “My friend Nika is one of the original friends from my first tour of Japan. She writes gorgeous and adventurous songs. Mostly she does big band jazz shows now, but she also sings for the animation studio Ghibli and is a Buddhist abbot.”

They recorded this in remote locations with not enough gear and with zero material to begin with, recording in a car when it rained. “We recorded in a windowless room with the oil lamp playing percussion. We recorded at the Guggenheim family’s summer home in Kobe. I collaged or cleaned up everything later. This record was the product of a very easy feeling time, now that I’m looking back,” O’Neil recalls. “The OG group was all still living, there were no children to care for, the earthquake and Fukushima disaster hadn’t happened yet.” O’Neil feels lucky not only to have been able to “play, like actually play around with Nika and Geoff Soule and Norio Fukuda on the recordings,” but to be “given another opportunity to have fun and a real youthful exploration and celebration” decades into her career.

Medusa Smack

O’Neil collaborated with the filmmaker Vanessa Renwick on some of her films and “just had a fun creative friendship during the years I lived in Portland,” she says. “She’s always good at pairing artists with other artists and bringing it all together in her backyard or in her films. In the case of Medusa Smack, she got permission to use recordings of Harry Bertoia’s Sonambient sculptures after visiting some of his pieces that are housed in Eugene, Oregon. She had a commission to do a Northwest-based film.”

O’Neil had just moved to L.A. and Renwick sent her to the Museum of Jurassic Technology to record the bell wheel they have there for inclusion in this score she assigned O’Neil to make. “So,” O’Neil says. “This is what I came up with as the score for her film!” Important Records was releasing a collection of Bertoia’s recordings and asked O’Neil to lend the music to the split with Eleh as part of their Bertoia celebration season.

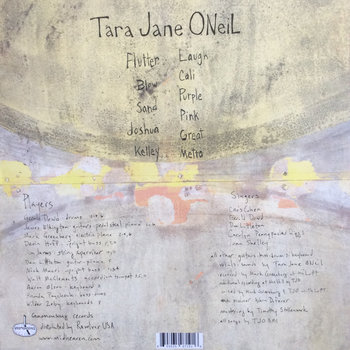

Tara Jane O’Neil

Vinyl LP

Following two decades of resisting the singer-songwriter label, O’Neil finally set out to intentionally make a singer-songwriter record. “I never felt like a singer-songwriter,” she says. “I was doing lots of dance performance and some scoring, and after making Where Shine New Lights, I felt quite resolved as a person misidentified as a singer-songwriter. But I like singer-songwriters and their music, so I figured after having made all the heavy music, I could do whatever I wanted—and I wanted to make a singer-songwriter record. And it ends up being kind of heavy. There’s a definite character in the writing, and I suppose also the sound, of healing from the death of my father.”

Most of this album was recorded largely live with a band at the Wilco Loft thanks to Mark Greenberg (Coctails, Eleventh Dream Day), whose relationship with O’Neil goes back to the very early Rodan and Drinking Woman (another band she was in at the time) shows at the Lounge Ax in Chicago. While they were hanging out at an Eleventh Dream Day show in New York, Greenberg casually mentioned that O’Neil should come record her new album at the Loft. “It was appropriate to the songs tracked there,” O’Neil says. “I wanted them to be live and I wanted to be a guitarist in an ensemble playing those songs. Often, I’m tracking alone and then calling others in for overdubs, or maybe I do it with one other person live, but he put together an amazing group of people and the Loft is a playground of incredible gear and incredible vibe.” The session features James Elkington (Horses Ha, Eleventh Dream Day), Gerald Dowd, Nick Macri (Euphone, Stirrup), and Greenberg himself.

O’Neil sent rough mixes she made to the musicians with no notes, they chatted out the chords, and then they just went for it in the studio without much conversation other than some direction from O’Neil around “feel.” Bassist Nick Macri recalls the sessions as being free-flowing and unquestioned. “It felt light and we all had a nice time,” he says. The remainder of the album was made in O’Neil’s home studio in California with Devin Hoff, Wilder Zoby, Walt McClements, and string supervisor Jim James. She brought it all back to the loft to do final mixes.

“A respectable indie label head graciously declined to release it and asked me if I knew what I was doing,” she remembers, laughing.

Yoake: Music From and Near the Film

“I was asked to do music for a feature film by Nanako Hirose, a director in Tokyo,” says O’Neil, who enjoys film scoring work and would love the opportunity to do more. “She is an enthusiast of my records. I’m not sure how that came together, but friends in Tokyo had some hand in it.”

In O’Neil’s experience, film cues are short pieces made to fit within the director’s edit, so many of these tracks are the exact length of scenes. “But this record I made includes drafts and longer versions of the music generated by the film,” she says. “A few pieces were included because they share a similar sonic space and general vibe, like ‘Loop,’ which I began during a residency at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn.” O’Neil would use her guitar as a mirror to what she was watching and record these drafts while watching the scenes for the first time. “Of course they end up being sculpted and solutions are discovered upon many subsequent viewings, but I try to keep my initial response to the film inside the final music,” she says.

Songs for Peacock

Vinyl LP, Vinyl

Songs for Peacock is a mixtape, a simultaneous homage and distortion of songs that were popular around the home she shared with her older brother Brian in 1983. It was created with a borrowed drum machine and a simple synthesizer in the fall of 2019, in the wake of his sudden death by overdose. The process of creating it was a kind of exposure therapy for O’Neil. “It was a way to cope with my grief and the process was a way to get to hang out with him in my favorite version, that being tweens and teens and listening to radio new wave and watching him peacock around his new styles.” Released in the first pandemic summer and announced during the time of the racial justice awakening in late spring 2020, O’Neil thinks it got a little lost and at least one reviewer seemed to really dislike her song selections.

“I made this for me and for my brother and then had a thought one day to send it to Orindal Records, in case they might want to release it properly. So, I’m really grateful it exists. I’ve had so much important feedback from people who could relate somehow. This is just a gift of anomalous music that bonds me in some way to Brian. The cover art is from his stained glass work that was in his house, which now the world can see.”