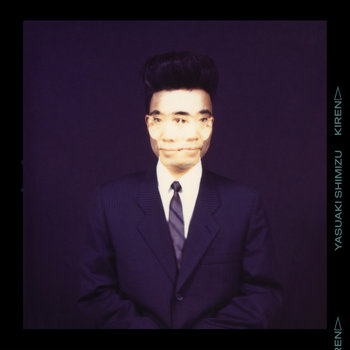

If you’ve found yourself taken by the sounds of 1980s Japan in the last few years, you’ve no doubt heard saxophonist, composer, and producer Yasuaki Shimizu at work. Whether you work, study, or vibe out to kankyō ongaku (aka Japanese ambient), fall down YouTube rabbit holes of city pop, or just thrill to the fusion of Fairlights, mallets, and bamboo, Shimizu was an integral part of Tokyo’s music scene during that heady time. He was in demand as a session musician, a keen-eared producer pushing at the parameters of pop music, and a solo artist whose albums fearlessly fused jazz, rock, and minimal music with African, Middle Eastern, Ethiopian, and Jamaican timbres. “I was very busy back then, throwing myself completely into work, not sleeping,” Shimizu says via translator from his home in Japan. “Basically, I was trying to grab every opportunity that came my way. I even served as producer a number of times for artists whose work complemented my own style. Which is why I ended up a nervous wreck!”

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD), Vinyl

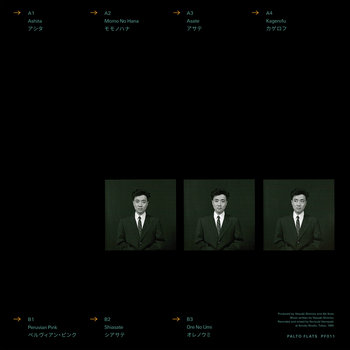

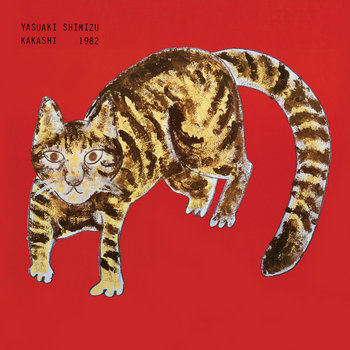

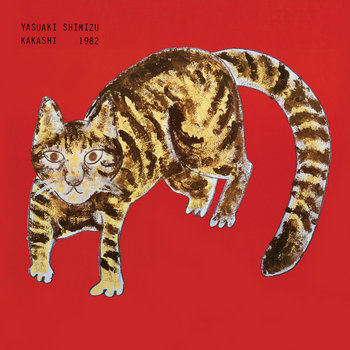

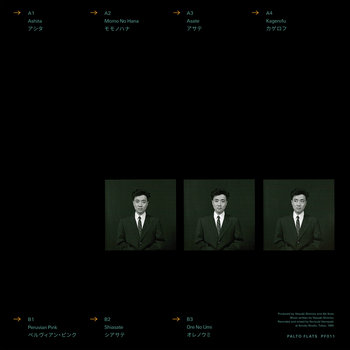

Over the past few years, Shimizu’s work has experienced a stunning renaissance, thanks to the diligence of New York-based label Palto Flats. Through that label, obscure albums like 1982’s Kakashi and 1983’s Utakata No Hibi (under the name of his old band, Mariah) experienced a new generation of fans in the 21st century.

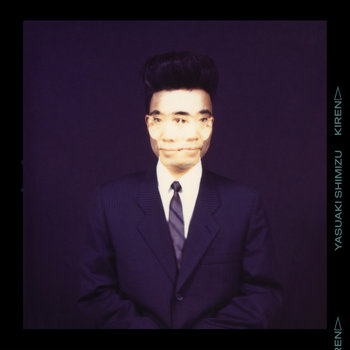

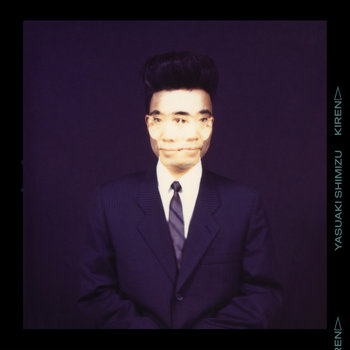

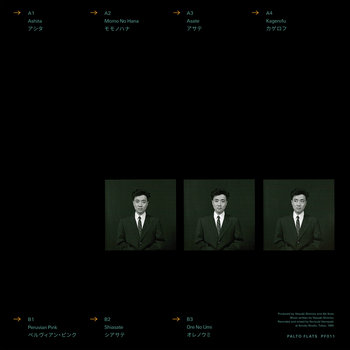

This month sees the release of Kiren, an unreleased album from 1984 on which Shimizu’s saxophone is pitted against an array of hiccuping samples, marimbas, off-kilter drum programming, and spiky melodies. ”To me, Utakata no Hibi, Kakashi, and Kiren were a related trio of albums, and my idea was to achieve a breakthrough with Kakashi that would pave the way for Kiren later,” Shimizu says. “But Kakashi‘s unexpected lack of popularity meant that marketing Kiren was lost, leaving it lying quietly dormant until this release.”

Shimizu grew up in the Japanese countryside near Mt. Fuji, where he took an early interest in music, learning how to play percussion, violin, guitar, clarinet, and piano. Around age 11, he took up the saxophone, which ultimately became his primary instrument. Throughout his childhood, he always kept an ear out for anything new and curious-sounding.

One night in particular sticks in his memory. “I was playing around with a radio transmitter I’d made when I heard something from outside the house and, fascinated, followed the sound outdoors. Striding off down the path between the rice fields, I paused halfway along the expanse of paddies to listen, and heard a chorus of thousands, tens of thousands of insects, like a wave of electronic sound washing over me. It was this experience that sparked my interest in sound and space, and which inspired me to begin exploring the many different sides of what we call sound.”

To that end, Shimizu turned to the radio, where he discovered American pop and folk, Indian classical, and more. “I grew up listening to music from around the world, and I believe memories of those sounds still drift about inside of me physically,” he says, singling out two in particular: the work of jazz saxophonists like Ornette Coleman and Rahsaan Roland Kirk, as well as NHK Radio’s weekly program Latin Time, which introduced him to South American music.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD), Vinyl

That driving musical interest led Shimizu to Tokyo in the mid-‘70s, a particularly fortuitous time and place in Japanese music. The scene, led by a new generation of artists who challenged the polite boundaries of Japanese music (Haruomi Hosono, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Hideki Matsutake), dovetailed with the nascent technologies being developed at the height of Japan’s economic miracle in the 1980s, showcasing cutting-edge synthesizers and drum machines. “I don’t think there is a fair assessment of him in the realm of jazz, pop, or experimental music,” writes Chee Shimizu (no relation), the regarded DJ, producer, and curator. “He is just an amazing composer, performer, and musician. I think Yasuaki-san has a very special position in the Japanese music scene.”

Regarding his evolution and maturation as an artist, Shimizu says: “I was mentally and spiritually a bit lost and struggling in the late ’70s. Burnt out, I decided to stop taking things so seriously for a while. Whether because of that I don’t know, but around this time I met a lot more new people. As I got to know them better, before I realized I found that the tightly bound web of distractions around me had naturally just fallen away, allowing all the information hitherto dispersed within me to start coming together in unison.”

A key collaboration with Akira Ikuta (who also served on Yellow Magic Orchestra’s management team) came into bloom, inspiring Shimizu’s own run of albums. “One memory I have of making Kiren is the intense back-and-forth I had with Aki Ikuta. More like intense mucking about, perhaps? Back then we were already sampling with tapes. At the start of each recording, we would take turns to randomly type any text that came to mind. The act of doing this would give meaning to our mood that day, our thoughts about the track we were laying down, and bring them to the forefront of our hearts and minds, albeit in an abstract way.”

Accordingly, Kiren features Shimizu’s saxophone fluttering atop an array of collaged backdrops: the whiplash and heartbeat rhythms underpinning “Asate”; the tribal drums and bird chirps scattered across “Kagerofu”; the James Brown-like funk of “Ore No Umi.” Such musical surprises await at every turn, producing an album that’s wondrous, even by Shimizu’s adventurous standards. “I never dreamed that I would be able to listen to a coherent volume of unreleased material from the early/mid-’80s,” says Chee Shimizu, who penned the liner notes for Kiren’s reissue. “He recorded this album when he was 30 years old, so it has a very cutting edge and gushing energy.”

As Kiren sat unreleased for decades, Shimizu’s pursued various other projects, from forays into Ethiopian music (he learned that Japanese music shares a similar pentatonic scale) to immaculate saxophone versions of Bach’s Cello Suites. Fortunately for us, the album was never far from his mind. “I certainly never forgot it,” he says. “I was waiting to meet someone who would truly love this album. I’m excited that thanks to Palto Flats, Kiren is about to see the light of day. I am simply delighted.”