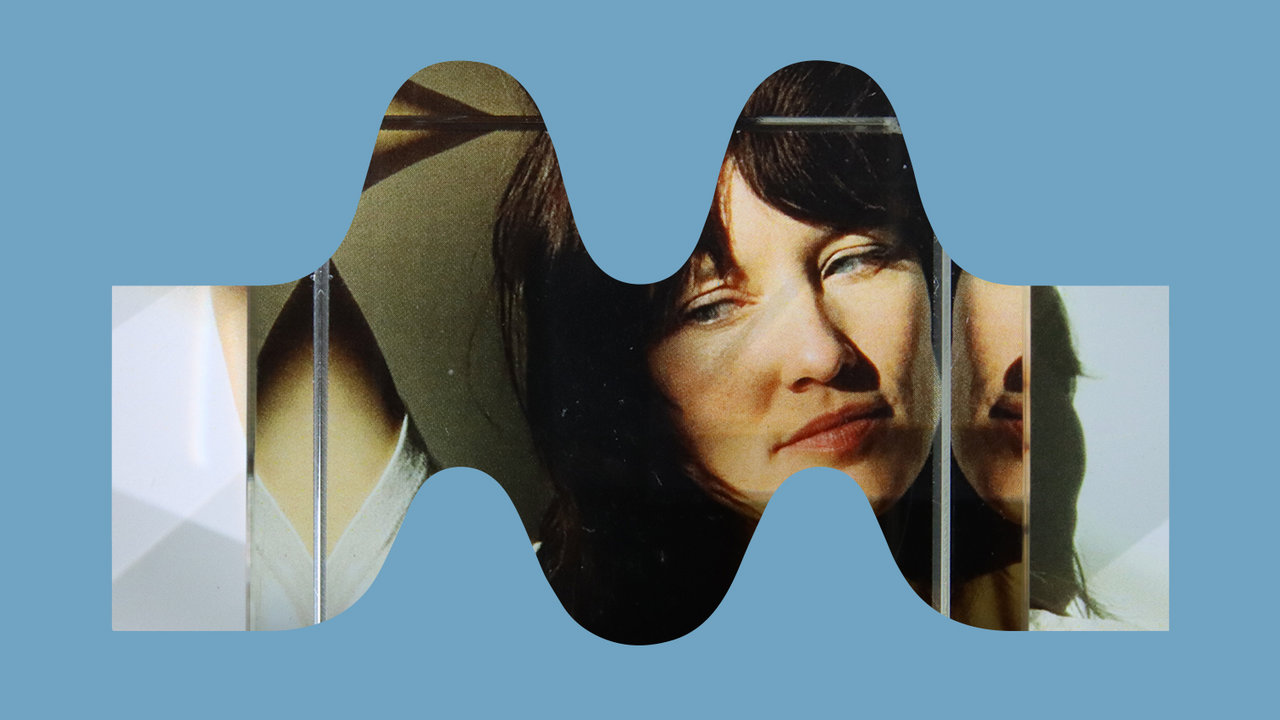

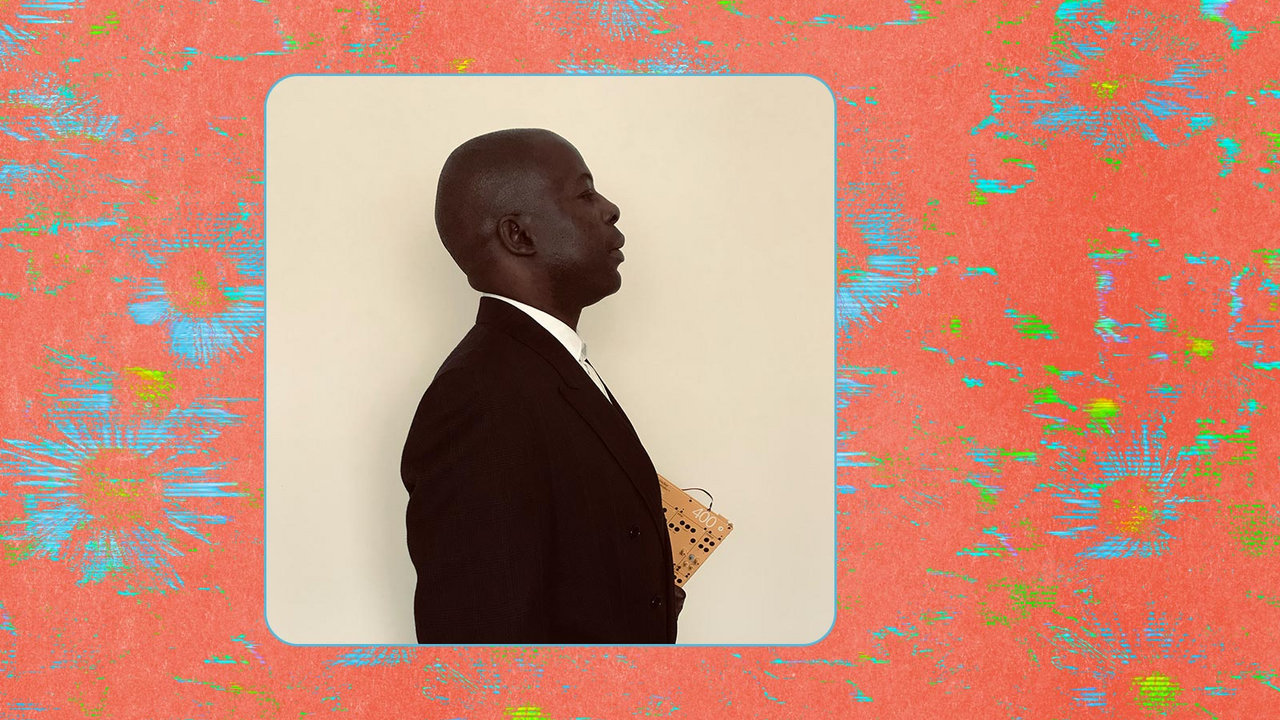

Photos by Jasmine Kwong

Photos by Jasmine Kwong

Raised in a single-parent household where money was tight and her mother was more artist than caregiver, Tomeka Reid was an outsider to the rarefied air of Euro-classical music. Before coming to Chicago, she was unaware of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), the organization founded in the 1960s that was—and remains—a foundational influence on jazz improvisation and originality. But Reid flourished in both jazz and classical environments, creating bold, distinctive hybrids of structured composition and spontaneous creation that earned her a MacArthur Genius Fellow in 2022, among many other honors.

Currently riding a creative high, Reid has a packed schedule for the first part of 2024, having already premiered a major work for her 16-piece Stringtet at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in late February, and performed with her quartet at the Big Ears Festival in late March. Later this month, she’ll play gigs as a part of Myra Melford’s Fire + Water Quintet and with the experimental group Hear in Now. Also on deck are commissioned compositions inspired by the music of Duke Ellington for concerts in Berlin and at the Kennedy Center, and the performance of a refined version of the Walker concert at Dartmouth College (where Reid is an artist in residence) with the full Stringtet, before taking the group into the recording studio for two days.

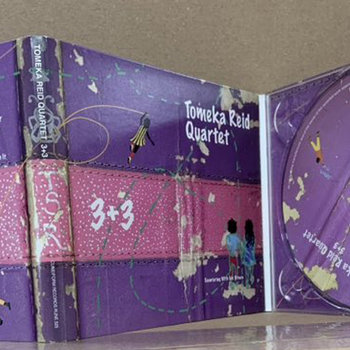

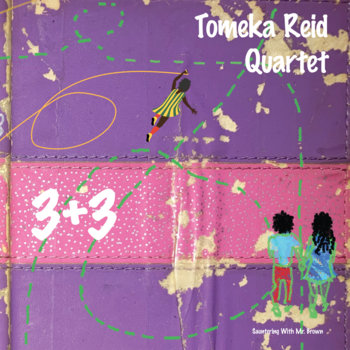

The final week of this month brings the much-anticipated release of the Tomeka Reid Quartet’s third album, 3+3, a gorgeous tour de force featuring improvisation and some piquant electronics mixed in with the band’s vibrant interplay over the course of three suite-like compositions.

We caught up with Reid in early March following her Stringtet show in Minneapolis.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Let’s begin with the biography, because you certainly didn’t have a typical childhood. What was it like being in elementary school where you lived in Washington, D.C.?

Well, it was crazy. I was going to this French immersion school in fourth grade and everyone else had been there since kindergarten. I kept getting pulled out of class because I couldn’t talk—you would get detention if you spoke English. Even on the playground they wanted you to speak French. So I couldn’t make any friends. But the one place you could communicate was in orchestra. My elementary school teacher said, ‘She has cello fingers,’ and recommended lessons, but we couldn’t afford it. She got me a Suzuki grant, but my mom was kind of an anti-mom, so that didn’t work out. But the school provided me with a cello, and I finally did get some lessons in 10th grade.

I read that you loved Elvis Costello and The Cure. When was that?

Around fifth grade. We couldn’t afford albums, but we would listen to the radio, a whole variety of programs; not much jazz, but there was 20th century classical music on Sundays and new music like Sonic Youth. You never realize what you are taking away from it. But I was always listening to the radio, because it was my friend.

I used to feel kind of weird because I grew up listening to all this. I didn’t grow up in the church like a lot of Black musicians, and I wasn’t in Suzuki at the age of three. But I realized that putting all my experiences together is what makes me me. Even though my mother and I had a very challenging relationship, that helped inspire me to go forward with my art, because I realized that’s what she wanted but had been unable to do [herself]. People are all doing the best they can.

Did you go to college at the University of Maryland right out of high school?

Yeah, after the first year, I was the only undergraduate cello major. The others were going for the doctorate or masters, coming out Curtis or Julliard. So again, it was sort of traumatic.

An extension of high school?

No, because I learned cello music. Even after, ‘Oh, I’ve got to play after those guys!?’ I was hearing the Beethoven Sonatas, the Rachmaninoff, the Prokofiev, the Britten cello suites. So beautiful. But I was technically behind. That pushed me to practice and practice and practice. I remember Sais—Dr. Sais Kamalidiin, he was my theory teacher in high school, who was there finishing up his PhD, and is now someone I basically call my dad—would encourage me to try other things. Like, ‘This rock band wants a cello, you should try it,’ or ‘My friend is in an African drumming ensemble and you should join it.’ But I was too shy and timid and felt I couldn’t do anything but practice. At the time, I wanted to be a composer. How could I do that if I couldn’t even master my instrument?

Compact Disc (CD)

When did things finally begin to open up for you?

In the summer of 1998 I swapped apartments with my sister who was living in Chicago. That’s where I met Nicole Mitchell. And she was like, ‘We should try improvising!’ And I didn’t know what she meant by that. This whole world that I’m now involved with was unknown to me at the time. Because for me, jazz was tunes and standards and stuff. So I had a glimpse into that. Nicole said, ‘If you ever come to Chicago, you can join my band [the Black Earth Ensemble].’

Then I went back and did my last year of undergrad. That’s when Sais and I did these local gigs at cafes—he had shown me some Rufus Reid basslines [I could play on cello] while he played flute and I was learning chord symbols, things like that.

When I moved to Chicago for grad school [in 2000] I reconnected with Nicki and started playing in her band. And I was like, ‘Wait a minute, there are no chord symbols! And now you want me to make these sounds that I have spent the past five years not making?’ [laughs] So yeah, that’s how the journey began. I learned about the AACM. I really didn’t know about them prior to moving here to Chicago.

You have this fascinating combination of honoring the past while your music synthesizes all these different elements and pushes toward the future. You are writing a book about the women in the AACM and have been a treasurer of the organization. You founded the Chicago String Summit that is now an annual event that brings together string players of all different disciplines. You’ve played a major role in raising the profile of other cellists—especially Abdul Wadud. You have a doctorate in music. You are like a progressive archivist faithful to institutions—you have a desire to organize and celebrate legacies—even as your music varies from formal composition to free-wheeling improvisation. Where does that come from?

I don’t know. Part of it is I was raised to be respectful of my elders. Even thinking about the relationship with my mother, I think it is important to know the context of things. I always wanted to know about my family history. I didn’t grow up with my bio dad. One of the reasons I have been doing so much stuff this year is that during the pandemic, I spent a lot of time being a caregiver for my grandmother. She grew up as one of like four Black families in southwestern Wyoming! Her parents were in a Black traveling vaudeville show.

Wow!

Yeah. Her mother’s birthday is the day before mine, and she was a dancer and her father was a singer. To me, that was so fascinating and it informs—you don’t have to be stuck in the past, but it is good to understand what has brought us to this point and also, I think, to honor these people.

People will say, ‘You are the first jazz cellist.’ No! There is a history of it. There is Sam Jones. There is Oscar Pettiford. There is Doug Watkins. They are what I’d call the bass cello players. For my thesis, I transcribed these different things to figure out what they did on the cello, and I discovered they tuned the cello like a bass, which is why they improvised the way they did. If you listen to Ron Carter play cello on an Eric Dolphy record, he sounds totally different. So I wanted to find out how this language was developed on my instrument.

And then I want to acknowledge the contribution that Deidre Murray has made, or Akua Dixon has made, and of course Abdul Wadud, who I always speak of. For improvisational music, Abdul was such an important figure—to me, it’s like how Pablo Casals was with the Bach Suites. He should be more of a household name. If he played the trumpet or something, I bet more people would know him.

So yeah, my practice is performing on the cello and composing, but I also think I should be an advocate for all strings and improvisational music, which is what the String Summit is about. Like, ‘Hey! We exist! And there is amazing stuff I want to share with you.’

Compact Disc (CD)

You’ve talked a lot about being overwhelmed trying to absorb things in your early years, but that obviously isn’t a problem now. I know it is gradual, but when do you think you really felt like you were a part of the firmament?

In 2009 I started my doctorate, because people were asking me more and more to do improvised music, and I thought I should study it more. I later realized I was already studying; I was just doing it at the club. But it is alright to have the paper, too. I had a different background; I hadn’t grown up playing in jazz combos.

I would really say that it wasn’t until maybe 2017 that I started feeling more comfortable. I just kept playing and playing. And I also realized what I love about collective improv is it is not just on one person—it really is about the collective. Everybody is working together to make it a beautiful musical moment. And I think that perspective change helped me to realize I’m a part of something that is greater than myself. And that is “the power is stronger than itself” idea [that is the motto] for the AACM.

Which brings us to 3 + 3, this third album from the Tomeka Reid Quartet. The first two were widely praised, especially Old New from 2019. But this one feels like it has a symphonic sweep to it, like movements and sections within movements, but also grooves.

I like all the music in the first two records. But in the past I felt, ‘Oh I need to write a blues tune and I need to show the cello can play in jazz and that I can play in these keys.’ And on this one I was like, ‘Nah. I want to play what I want.’ I like D minor. I like A minor. I like those keys because my strings can ring. I can make use of my open strings and stuff like that. So that was something that I did think about with this. I love free improvisation. I think in the past I have been a little bit bashful about that part of me—I mean, I do it so much, but not in my own writing. This time I am like, ‘You need to write who you are, and you do a lot of free improv. If people don’t like it, well, hopefully they’ll keep listening and they’ll hear the tune part.

We’re multifaceted beings. And I want to be able to share. I love dancing, I love hip-hop, I love that type of groove. Which I think you can hear, even in the Stringtet you can hear those things. So why do we have to have just the free improv over there and not here? And I feel l was doing that to myself you know? So on this record I have the long melodies, I have the groove, I have the swing. I have something I was excited to add. I had not been using electronics, I was always trying to figure out how to make electronic sounds acoustically. But this time it was really fun to add them. I don’t use them all the time, but there were some epic—well, epic to me [laughs]—moments where I put them in there. And then I still have my acoustic sound, too. I want to put it all in there because I do all of those things.

So 2024 has been a whirlwind thus far. I’ve heard one of the great things about a MacArthur Fellow is that it enables you to have time to recharge. Is that in your future? Are you a beach person?

I want to be that type of person. I just flew back here to Chicago for two days to see my husband, who I haven’t seen since January, before going back on tour. I am trying to move back to New York; figuring out how to make that work. My husband is David Brown. He teaches architecture and he wrote The Book of Noise Orders. He is starting a nonprofit here, dealing with his work, and it would be nice to be able to move back and forth fluidity between the two places. I don’t think I’ll ever be completely out of Chicago, because it has been such a home base and such a gift in my career. It is where it all started.

The next big thing is a Stringtet performance at Dartmouth on April 11th and then on the 12th and 13th we’re going into Firehouse 12 to record—their Studio B is supposed to be really good for strings and I’m super-stoked about it. I love doing things, but I realize that for my own health and brain clarity I need to just chill. And reflect. And be grateful. There are people who are stuck and don’t realize their dreams—or can’t, because they live in a war-torn country.

I didn’t imagine anything like this—I was just trying to learn how to play the cello. And it has taken me to play with people all over the world, with so many people. I’ve tried so many foods, seen so many things—all because of this piece of wood!

Well, I play a carbon fiber cello now. But you know what I mean.