April 4th, Detroit, Michigan

Venue: The UFO Club

Line-Up: Dummy, Idle Ray, Deadbeat Beat

Tonight’s show is packed out, in no small part because of the strength of the line-up: local garage stalwarts Deadbeat Beat and Idle Ray, a three-piece featuring real-life Detroit DIY legend Fred Thomas. Of all the shows on tour, this will probably be the sloppiest set Dummy plays. It will also be my personal favorite.

All tour long I have been playing a game with myself called “What kind of band is Dummy tonight?” in which I try to decide which rock subgenre suits them best in any given city. In Detroit they are a psychedelic rock band, likely due to the fact that they’re tired and so not as locked-in as usual. There’s an unpredictability and wildness to the set, not descriptors I usually associate with Dummy. It feels very cool, very Detroit. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it is tonight that Trainor will fuck up his amp, when he decides to turn it to face a couple of crowd members who are talking too much during the set. It won’t be fixed until the band is in Baltimore the following week.

We have a lot to talk about the next morning on the drive to Columbus because Stereogum has just published a rather histrionic article detailing the difficulties of being a touring musician in 2022, written in response to a viral tweet by “reasonably successful young band” Wednesday about how much money they lost touring SXSW. Though some reasonable points are made, the tone of the article is overwrought and includes some truly baffling quotes from Z. Cole Smith of DIIV about how “there’s a long, long tradition of people wanting musicians to suffer.” Wait, so, people actually do think making music shouldn’t be fun?

“The suffering aspect of it, like, any endeavor you undertake is going to be work. Work is going to be hard,” points out Ewell. “For music, obviously it’s very fun and it’s very fulfilling to play shows and have people be fans. But at the same time, there’s all this bullshit you have to do and all the stuff that sucks all around it. It’s not really fun to be sitting in the van for hours and hours and hours.”

Yet what the article makes most plain, likely unintentionally, is the fact that many so-called “indie” bands seem to believe music owes them something simply because they play it and that touring should be without challenge—Smith says that sleeping in a van is “inhuman conditions,” which feels a bit melodramatic and ultimately a little entitled. It’s not that Dummy is unsympathetic to the difficulties of being poor artists—they’re all poor, too—but everyone’s scrambled around in the underground long enough to have encountered bands with this kind of attitude and seen firsthand how it poisons the relationships between people who might otherwise be natural allies.

“They’re like, ‘Oh, I didn’t do anything for this show. I didn’t post it on Instagram. I didn’t flier, but I need you to pay me $300,’” says Trainor with disgust. “It’s like, ‘What did you do?’ You sat in your room and wrote a song. That doesn’t automatically mean you get to make money. It’s insane. Just make your music for you. If you actually care about music, you’re making it for you. If people connect with it, that’s amazing. If they don’t, that’s okay. Not everyone who picks up a guitar deserves an audience, that’s just not how it works.”

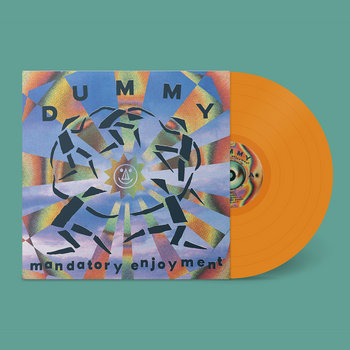

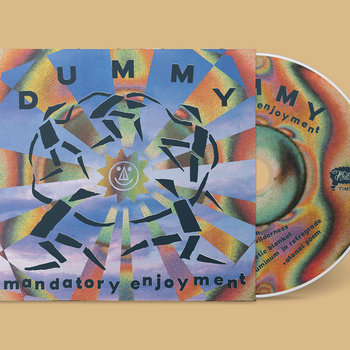

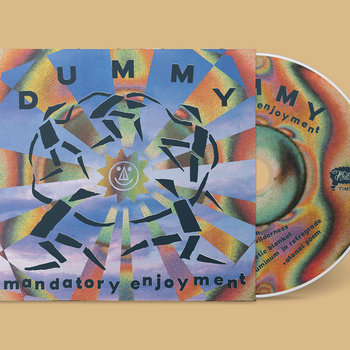

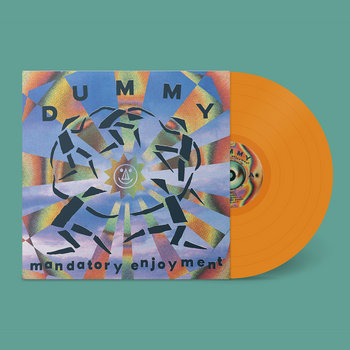

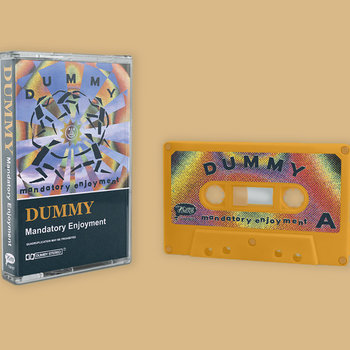

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD), Cassette

So many of the assertions made in the Stereogum article as statements of fact are being punctured every day I’m on Dummy’s tour. For example, if we accept the premise that touring successfully is only possible for bands with “trust funds or celebrity parents,” then Dummy, who have neither, must be a magical unicorn because they’re not only not losing money but, with merch sales included, they’re doubling the base dollar amount Trainor calculated at the beginning of tour as the target the band would have to hit so that nobody went home broke—and they’re doing it every night. Then there’s the assumption that streaming numbers are an accurate reflection of how strongly a band is connecting with the sort of listeners who buy merch, go to shows, tell their friends—aka, the sort of listeners you need in order to have a successful tour let alone a sustainable career. To that point, “reasonably successful young band” Wednesday is noted in the piece as having “about 250,000” monthly listeners on Spotify. As of this writing, Dummy has 23,541. The cognitive dissonance is mind-boggling.

“It seems like these bands tour because they’re just like, ‘I want to go on tour,’” says Trainor. “For us, it was laid out like, ‘You should tour, it makes sense for you to tour.’ Even if the demand is small, there was a certain amount of it to where it was like, ‘Okay, let’s just do it. You could argue that us deciding to be poor and be artists is a privilege—or maybe you couldn’t argue it, it’s true. But we’re taking a pretty big risk to some degree, for just saying ‘fuck it’ this year and touring so much, because it might end up being for nothing.”

It’s easy to get on a high horse when your band is doing well, but Dummy are quick to attribute the success of their current tour at least in part to the goodwill generated by the work that the members, especially Trainor, have put in as upstanding citizens of the underground music community. “This whole band is built off of stuff we’ve been working on for decades,” says Ewell. “Everybody’s been playing in bands and touring the country, doing the shit for years. That’s such an important piece to have. It wasn’t like overnight we made this tour work.”

“[Bands] think they can post pictures on Instagram and people will think their band’s good and then they’ll get a PR person or whatever,” says Maatman. “And that does happen. But the way to guarantee that you can get to that stuff is if you just do it yourself. We happen to be a very lucky band in that we have somebody who has a lot of experience with being on tour, meeting bands, booking shows, doing PR. I’m an artist, I have connections. Everybody has their own specialization in our band. We didn’t have to learn to do certain things. We just had that.”

Not that people outside of Dummy seem to realize any of this. Trainor is constantly fielding messages from artists asking how the band got signed to Trouble in Mind and linked up with Ground Control; what about their PR person, how did they get one of those; and then the whole thing with Sub Pop, can he share a contact? He finds these inquiries “insulting in a weird way,” with their implication that there’s a cheat code to replace decades of dedication, some magic button that will leapfrog the years of being poor and having your band ignored but continuing to do it anyway because music is the only thing that gives your miserable life meaning. Everyone wants to know what time it is, nobody wants to know how to make a watch.

“I just want to be like, ‘I make good music.’ For Dummy, that’s literally all it is,” Trainor says. “It’s purely based on our music being good to us and other people. We’re doing things in the most honest way you can do it as a band. It’s a culmination of years of work, and years and years of making friends in all different places, supporting those friends in their endeavors and them supporting our endeavors.”

“Bands want to have a booking agent and manager,” he continues. “When the band has 1,000 followers on Instagram and they have a manager, I’m like, ‘Why?’ That’s just someone trying to leech money off you. They want to skip the hard work. They just want the aesthetic of success.”

“But I think people in the real world don’t care how hyped your band is by journalists or whatever,” says Ewell.

“No, I think that’s not true. I think people in the real world do care more about that these days than they do about the band that’s worked really hard,” insists Trainor. “I mean, we got added to a playlist and literally our listener count tripled.”

“That’s people who have heard the song once,” says Ewell. “It’s not as simple as just: you’re a band and you have enough followers so go on tour and play your songs on stage. That’s not enough to have people care about what you’re doing. You have to, like, try.”

“For a band like ours,” Trainor clarifies.

But what does that mean, though, for a band like Dummy? Ben Parrish, label director at Joyful Noise Recordings and publicist for Sahel Sounds, writes over email that he thinks of Dummy as “an indie band in the classic, independent sense associated with cultural institutions like SST, Homestead, or K instead of ‘indie’ as the respectable middle-class aesthetic made popular by content like The OC and Garden State or acts like The Postal Service, The National, Phoebe Bridgers, etc. The approach that they’ve taken towards getting their music out there feels sort of like a ‘rock’ parallel to what we’ve been doing with bands like Les Filles de Illighadad and Etran de L’Air at Sahel Sounds. Instead of spending tens of thousands of dollars on publicity in an attempt to get on sites like Pitchfork or Stereogum or focusing on trying to get on Spotify playlists, they’re participating in actual music communities, interacting with people that buy physical media, and making genuine connections.”

“There are decades of evidence that bands don’t need to do things like lose thousands of dollars performing at SXSW, beg to open for larger acts for $200/night, or play the first of 15 bands at a festival to connect with an audience,” Parrish continues. “I’ve been working at labels for 17+ years now and while it’s a good (temporary) morale boost, getting a YouTube embed in an article about the 25 new songs released this weekend doesn’t create a successful tour or career. From following Joe’s Twitter for the past year, it’s clear that Dummy put a lot of thought into playing shows with strong bills and exciting local acts in each city.”

With all of this in mind, it’s hard not to think of the Stereogum article as part of some industry psy-op designed to recast the labors of love as pointless drudgery if there isn’t an immediate financial reward. It’s a campaign that’s been going on for many years, helped along by music-journalists-who-should-know-better bloodlessly reframing decades of ethics and principles in independent music as “posturing and sanctimony” in order to argue that selling out is good, actually, and also you don’t have a choice, idiot, as if there were something shameful in believing that music, of all things in this horrible world, can still be pure. But maybe it’s less complex than that.

“I think that a lot of this is the permeation of rich kids in working class genres like punk and DIY music where they’ve decided, ‘Artists deserve to get paid,’” says Trainor. “I think that’s a rich kid mindset. Obviously, I’m not saying music isn’t valuable monetarily.”

“But it isn’t,” says Ewell simply. “It actually isn’t.”

April 5th, Columbus, Ohio

Venue: Dirty Dungarees

Line-Up: Dummy, Egon Gon, Powers/Rolin Duo

Dummy is playing in Columbus tonight, at a laundromat with a bar in it called Dirty Dungarees—”Dirty’s” to the locals. Also on the bill are acoustic experimental act Powers/Rolin Duo and a loud alternative rock band called Egon Gon. Later, we will be staying at the home of Matthew J. Rolin (who helped Trainor book the show) and Jen Powers of Powers/Rolin Duo, where Maatman will be very taken with the couple’s oversized black-and-white cat, Catthew J. Meowlin.

As you can imagine, a laundromat—even one with a bar in it—in Columbus, Ohio, is not the most comfortable of places to chill while waiting for a band to play, so as the damp gray day begins to transition into drizzly blue twilight I go sit in the van with Ewell, who is also hiding out, and ask him what his favorite part of the tour so far has been.

He says that it feels good to finally be able to play music for people in person, which makes sense for a band whose major career milestones thus far have all taken place during a pandemic that put a digital iron curtain between listeners and artists. “It’s very weird to try to wrap your head around, like, ‘Oh, these people like our music and really want to support us.’ That’s fucking awesome,” he says. “That’s way more than we ever expected to happen even though, you know, that was our hope.”

Then he becomes poetic. “The whole point of this band and doing music and everything is to give other people what we’ve gotten from music, which is so much enjoyment and connection and love,” he says, his voice intensifying with every word. “Just loving music and having music be something you can dig into as a fan is such a special thing. That’s what we wanted to possibly do for other people.”

Tonight’s show is a good one. It’s not a huge crowd, but everyone who attends is endlessly appreciative; several people at the merch table make it a point to thank the band for coming to Columbus because nobody ever does. Powers/Rolin Duo’s set is also a highlight; Ewell in particular enjoys the fact that the audience sits down and zones out while the pair use fingerpicked guitar and hammered dulcimer to create wafting clouds of meditative sound. In sharp contrast to the tranquil quality of the music he makes with Powers, the bearded, effusive Rolin is as punk rock as they come, unafraid to punish the audience for a good cause. “Give Dummy fucking money,” he bellows after Powers/Rolin Duo have finished playing. He holds up a plastic jar and shakes it emphatically. “Put money in this, buy merch, Venmo them. I mean that in the most loving way. I’m not going to hunt you down or anything.”

After the show, I smoke a cigarette outside with Rolin while he tells me a bit about his life in music, how he fled garage rock-crazed Cleveland for the more thoughtful environs of Chicago post-rock before meeting Powers, whom he calls “the love of my life,” and moving to her hometown of Columbus. Rolin sums everything up by calling himself “an idiot who let music destroy my life.” I’ve heard that phrase before. Jon Fine of ‘80s post-hardcore band Bitch Magnet uses it in his memoir, Your Band Sucks, to refer to people so committed to music that they’re willing to sacrifice everything—their youths, their bodies, any semblance of straight world stability—just to be part of it. Bitch Magnet, who were also from Ohio (if you count Oberlin, which I know a lot of Ohioans don’t), probably played Columbus a million times. They probably played laundromats, too.

April 6th, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Venue: Thunderbird Music Hall

Line-Up: Dummy, The Gotobeds, Century III, Gaadge

In the interest of full journalistic disclosure, I will be honest and say I don’t remember much about this show because I got ultra, super, mega fucked up with the Gotobeds, as I have more or less done every time I’ve visited Pittsburgh since the first time I went there in 2019, when I got (slightly less) fucked up with the Gotobeds on the company dime—and you can read all about that on Bandcamp dot com!

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD), Cassette

April 7th, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Venue: The Ukrainian Club

Line-Up: Dummy, Mesh, So Totally

I’m so hungover that I can barely speak on the road to Philly, a feeling that doesn’t dissipate until we arrive at the Ukrainian Club in Philadelphia and I start drinking malty Ukrainian beer. It’s a stressful night anyway. The original venue got shut down and the show had to be moved at the last minute, so it’s a disorganized mess and nobody knows what they’re doing and it sounds like shit, and it’s also raining. But Trainor points out that there were 77 paying people at the door, “So it’s not like it bombed, it’s just the room was too big for us.”

The show is most notable for the attendance of a Dummy super fan, who is following the band around the northeast. He gifts Dummy an eighth of weed, the packaging emblazoned with the name of their band and the name of the strain. He proudly informs them that he gave the same strain to the Brian Jonestown Massacre, so now Dummy can get high on the same shit as the BJM. Ha ha ha. It helps with my hangover, anyway.

April 8th, Boston, Massachusetts

Venue: The Lilypad

Line-Up: Dummy, Carinae, Strange Passage

On the way to Boston, on the edges of Westport, Connecticut, the van dies again. Panic sets in—for real this time. This is a particularly bad place to have stalled out because, as one of the wealthiest cities in the state, there are no sidewalks, no public restrooms, and nobody within 10 miles willing to lift a lily-white finger to help a touring band from California sitting in a commuter parking lot, freaking out. The band go back and forth about whether it’s worth it to risk continuing to drive and maybe blowing up their van completely, or if they should just cancel the show and try to figure shit out here.

When it seems like canceling the Boston show is the only way to go, Ewell pipes up from the back seat. From his perspective, calling off the show without any solid information about what’s wrong with the van means that the band is also preemptively giving up any money they might make from it. “The van is probably fine,” he argues passionately, “It’s the same thing as before. We just need to make sure we have enough gas in it and when we get to Boston we can get it checked out.”

Trainor throws up his hands. “Fine, let’s just go. I don’t even care.”

And so we do. In spite of the earlier stress, the drive itself is a rather lovely one. The northeastern sky begins to turn pink and blue as it arcs overhead. O’Dell is driving and he and Greshowak are playing Neil Young. The music is warm and familiar and comforting. I lean my head against the window and think about how often people say that being on tour isn’t “real life” and how, in some ways, being on tour seems closer to how life actually could be if we weren’t so hellbent on torturing ourselves with ruminations on everything that didn’t happen, might happen, never will happen—every possibility a heartbreaking reflection of the many ways you will fail. But take all that off the table and suddenly life is reduced to a series of simple questions with only simple answers: Are you hungry? Do you need to pee? Should we go to the show? No. No. Yes.

Ewell’s choice ends up being the correct one, as the show is packed and Dummy makes a bunch of money—and the van is, at this point, fine. “The whole point of tour is to play shows so I’m glad to be doing that instead of sitting in a hotel worrying about the van,” says Maatman.

“I hope you’ve gotten enough to write about,” Trainor says to me as people mill around on the sidewalk outside the venue after the show is over.

“I think so,” I say.

April 9th, Easthampton, Massachusetts

Venue: Daily Operation

Line-Up: Dummy, Carinae

For some reason, hotels in Boston are extraordinarily expensive so I book us into a Quality Inn in Lexington, Massachusetts, wherever that is. The room stinks of cigarettes and just as we’re falling asleep, there’s the sound of shouting voices and glass breaking outside. Maatman is the only one who seems concerned, jumping up to look out the window to check on the van—all the boys have fallen asleep. But it ends up being fine (for us), since it’s just a dude getting the shit kicked out of him in the parking lot. This fact is confirmed when said dude shows off his swollen face to Greshowak in the morning. He and O’Dell have gotten up early to take the van back into Boston to be checked out and have the oil changed.

The rest of us are stuck at the hotel until they return. After asking for a late check-out and drinking about twelve cups of shitty lobby coffee, I decide to read Pitchfork’s review of the new record from Wet Leg, one of many mediocre British post-punk groups who you’re more or less informed that you like, because you’re into guitars, right, idiot? Mandatory Enjoyment, as Dummy would say.

The review is infuriating. The writer praises the band for not having any loyalty to the music they play, calling them “carpetbaggers in a carpetbagging genre”—as if Wet Leg were totally sui generis and didn’t have the immediate advantage of several powerful music industry figures giving them a boost when so many others struggle in obscurity and poverty forever. No wonder young bands have been brainwashed into thinking there’s a shortcut to success, and there is little value in cultivating genuine connections within independent music. They need only pay a publicist or get a booking agent or snuggle up to the right people and everything else will follow. Why wouldn’t they think this? When we celebrate puerile, exploitative bullshit as worthy of respect because it is puerile and exploitative, it lowers the bar for everyone. Suddenly I’m mad as hornets. Making music shouldn’t be fun.

The show in Easthampton is another one booked by Ground Control with a big guarantee. It takes place in a pop-up restaurant inside a converted mill called Daily Operation, which kindly provides us all with free food that we eat in the kitchen. Tour boredom has fully set in for me at this point and, since it’s too cold to just chain smoke outdoors, I end up sitting on an amp one band or another has left sitting in the cavernous hallway outside the restaurant until show time. There are whispers that J. Mascis and Frank Black, who live in the area, might come out tonight, but they don’t.

April 10th, Brooklyn, New York

Venue: Baby’s Alright

Line-Up: Dummy, Zero Point Energy, Jobber

The drive from Springfield to Brooklyn—via Hartford, Connecticut where we unintentionally get food at a Bright Eyes-themed coffee shop—is my last long trip in the van with Dummy. For fun, the band begins to interview me. They ask what shows I liked best and I rattle them off: Pittsburgh and Denver because my friends were there, Detroit because it was the most rock and roll, Columbus because it was weird, and we all agree the Greenhouse deserves a big shout out for doing their part for Kansas City DIY. Musicians may get all the press, but it’s really the kids running venues, the promoters booking shows, the people running labels out of their bedrooms, and, yes, even the writers who keep the whole thing going: the people who let music ruin their lives. Dummy’s success is in no small part their success, and perhaps one reason for Dummy’s success is that they recognize this.

“I feel so grateful that for some fucked-up crazy reason Trouble in Mind decided to work with us, Popwig, Born Yesterday—all that shit is crazy,” says Trainor. “It doesn’t make any fucking sense to me. We can talk all day like, ‘Oh, the music’s good or whatever.’ But we’re extremely lucky that anyone wanted to fuck with us. And the thing with Sub Pop to me is un-fucking fathomable. We’re on the same label as Nirvana!”

“We’re not on the label,” Maatman reminds him.

“Whatever! The way that Nirvana started on Sub Pop was with a Singles Club single and we are doing that, too, that’s crazy.”

“I just feel very, very, very, very, very, very lucky that all this stuff has happened,” Trainor continues. “And I feel very lucky that it’s with this group of people who I care deeply about. That’s why I’m so excited to do so much touring. It’s really hard and a lot of work, but also I get to do it with all these idiots and actually have fun.”

“We’re lucky and we’re taking advantage of it! I’m never gonna have this opportunity again, whatever, I’m gonna quit my job and do this,” says Maatman.

“If none of this had worked out, and we were just writing songs and making little tapes in L.A. and playing shows sometimes, that would have been totally fine. None of this was the ambition. At all. Just making music was the ambition,” says Trainor. “If we continue to get more popular, that’s cool. But if we stay in this zone and we’re able to tour and make some money, that’s also fine. If we decide this isn’t sustainable or good a year of doing this, so be it. But we’re very, very lucky. But we also put so much effort into the music. So maybe that’s why it’s not luck. I don’t know.”

What is luck, really? Is it a series of events as startling as they are senseless that turn the wheel of fortune in your favor? Or is it a matter of dogged persistence without expectation of reward, of sending your call into the darkness night after night in search of some cosmic dial tone? “I used to believe in destiny and fate. Now I think it’s a bunch of bullshit,” writes Henry Rollins in his memoir about touring with Black Flag, Get in the Van. “I want more than a normal human life but now I see that I have to create it for myself. There will be no miracu-lous [sic] happening in my life. Just get in the van and go to another show.”

But maybe it is just getting in the van and going to another show that makes miracles appear. Maybe it’s the only thing that ever did. I think again of “the people who let music ruin their lives” and wonder if it’s not the opposite: it’s everything else that is trying to ruin your life by convincing you that music is a locked door that swings wide only for the fated few rather than a key passed down through the decades to anyone willing to grasp it for themselves; that you are alone in the universe instead of a link in a chain that winds around the world and stretches back to before you were even born, connecting you to all the people who ever loved music so much they destroyed their lives to save yours. They are brilliant stars in a great constellation that shines in the darkest of nights, and now you are a star, too. I can sense it, sometimes, while watching Dummy play, like vibrations coming through the floor. It’s as if I need only stretch out my arms to feel it course through my body, the love of music that transcends time and space and bonds me to this place and this band, and to every band that came this way before. What more could you possibly wish for? You are one of us. You belong.

All tour long Trainor has been picking out music to play, much of it weighted so heavily towards avant-garde jazz that even the adventurous Ewell can’t take it at times (he requested that Flaming Tunes be turned off because “it’s literally hurting my ears.”) Yet somewhere in Connecticut, Trainor turns around from the passenger and looks directly at me as he queues up a new tune.

“This one’s for you,” he says.

“Fucking finally,” I retort. “One for me.”

I’m already a bit emotional anyway, the specter of a return to the solitary life of a writer hanging above my head after two weeks with the band, but my heart dissolves completely as the song begins to play. It’s “Don’t Look Back” by one of my favorite groups, Teenage Fanclub.

Co(vi)da

And then we all got COVID!

Well, you knew this was going to happen right? It’s 2022 and all bands on tour get COVID sooner or later. Dummy may have been the exception to every supposed rule—going broke, sleeping in the van, etc.—but in this case, they were not, and neither was I.

When Greshowak texted two days after the band dropped me at home in Bed-Stuy after their (unmemorable) Brooklyn show to let me know that he and Maatman had tested positive, I was already laid up in bed, grateful for the small blessing that I was miserable at home rather than quarantining in a hotel room in Fairfax, Virginia, as the band had had to do.

I catch up with Trainor a few weeks later, after the band has returned to California; he says he’s been playing Call of Duty and watching a Netflix series called Alone ever since getting home. Everyone except O’Dell ended up getting COVID, and they had to cancel a bunch of shows because Ewell got sick enough that there was one point where they thought they’d take him to hospital. Oh, and their van died, too—this time, for real. “But even with that we lucked out,” says Trainor. “We have a friend in Baltimore who fixes cars and he fixed it for like $450, which would have been easily a grand from somewhere else. And then, also in Baltimore, I lucked out with someone fixing my amp.”

Still, despite getting clobbered by circumstances beyond their control, Trainor considers their tour a success. “Up until COVID, it was incredible,” he says. “That’s pretty much how I feel about it. There’s no way of knowing how the handful of shows we missed—in North Carolina and Atlanta and D.C. and Alabama—I have no idea. It could have been cool. It could have been bad. Obviously, I would have rather played the shows and found out. But maybe we saved the money in some weird way by not playing those shows and putting miles on the van. There’s no way of knowing that kind of stuff.”

Regardless of how rough the second half of their tour was compared to the first, Dummy is looking forward to getting back in their now-fixed van and out on the road again with Horsegirl, a band Trainor considers to be “like-minded in their taste. They’re always shouting out weird stuff that we like. The shows are all-ages and I’m sure there’s going to be a lot of younger people seeing kids making weirder guitar music, and I think that’s good.” The band will also be playing some shows between dates with Horsegirl, and Trainor’s currently working with their Ground Control booker on finding cool local bands to play with. “We’re doing more days off though,” he says. “I regret having less days off the road. We’re all old. We need more days.”

So, this is where the story of Dummy’s first full U.S. tour would seem to end. It is a happy ending, for all intents and purposes. In spite of the missed shows, the band did, in fact, return to Los Angeles with more money than they left with: a fact standing in stark contrast to the narrative of poverty and hardship pushed in these days of COVID and societal meltdown. But these dour proclamations ignore the fact that Dummy, and so many bands like them, are part of a larger story, one that doesn’t hinge on making pots of money or achieving mainstream popularity—that story is not over. And neither is this one.

May 1st, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Again)

Venue: Khyber Pass Pub

Line-Up: Pardoner, Mesh, A Country Western, Menu

Two weeks after getting dropped off in Brooklyn by Dummy and a week after testing negative, I have returned to Philadelphia to see Pardoner, a San Francisco band of whom I’ve been a fan of for many years, and who I used to see play all the time when I lived in the Bay Area. Their 2021 album Came Down Different was my favorite release of the last year, aside from Mandatory Enjoyment. I’m excited to see Pardoner play outside of California because, despite having released three full-lengths since 2017, tonight’s show is part of their first-ever U.S. tour.

I’m here on invitation from Sims Harding of Mesh, who opened for Dummy in Philadelphia and told me about the Pardoner show when we were taking whiskey shots at the bar at the end of that drippy, disappointing evening. He has kindly put me on Mesh’s guest list, which is dope because I had, rather obnoxiously, not even considered how I would “get into” the show—aka paying for it—now that I’m not “with the band.”

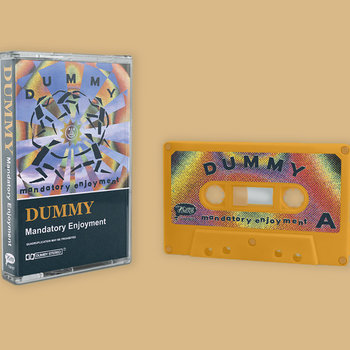

Cassette, Vinyl LP

This is a much better night in Philadelphia than the one the month before. The venue is packed with kids, despite it being a school night. “Give Pardoner money,” Harding instructs the crowd from the stage after Mesh has finished playing. “Because they rock!”

Pardoner sound great. Most of the songs they play are new; I’ll find out later that this is because the songs on Came Down Different are in so many different tunings that it would have been physically impossible for them to fit all the guitars they’d need to play them into their van.

I seek out Pardoner in the crowd after the show and, though it’s been years since we’ve seen each other, to my delight and surprise, the members of the band recognize me immediately. I ask them how their tour has been going. “Great, great,” they say. They’ve been sleeping on floors mostly, but all the shows have been good, and if it hadn’t been for some financial fuckery when renting their van, they’d probably break even at the end. They say they’ve been on the road so long that they’ve started cracking up, talking to each other in silly voices, their conversations a litany of inside jokes. I laugh because Dummy was exactly the same, and I tell them so. At the merch table, I purchase a tour tape and a t-shirt from drummer River van den Berghe, adding some extra onto the total because it’s weird out there for bands.

I run into guitarist Max Freeland at the bar after Pardoner has loaded out, and we catch up a bit. I’m very happy to see him. He tells me he booked the entire tour himself, all DIY. He’s a bit shocked at how well it’s going but even if that wasn’t the case, it wouldn’t matter. “I’m doing this for me,” he says. I congratulate him again as the conversation begins to wind down, wishing Pardoner a safe and wonderful rest of tour (they do, in fact, make it back to California without getting COVID, so you know, anything is possible.) For a moment I feel it again, that love of music that bonds me to this band and this place and to everyone who came before and everyone that will come after, the everyday miracle that is just getting into the van and going to another show.

“Alright,” says Freeland, making moves to leave the bar. “I’ve got to go find my band.”