Sound isn’t just a means to a musical end for Mouse on Mars. It’s everything; a form of fearless expression that’s free of limits and guardrails.

“Mouse on Mars has always been a research project of what sound actually is,” explains Jan St. Werner. “It’s not just about listening. It’s how information travels, the molecules in the air, and how you relate to the source of the sound—how you decipher what is actually happening and relate to the visual cues.”

St. Werner and Mouse on Mars co-founder Andi Toma first crossed paths in 1992, when the former asked the latter to mix his first CD (the glitch-in-the-matrix grooves of Slow, a collaboration with F.X. Randomiz). While neither of them was looking to form a proper band, Toma says they “quickly realized there are similarities in the ways we work. The moment of creation is more important than the result, and there is no ego about how a thing should be…Anything’s possible.”

“Our sounds didn’t match at all,” adds St. Werner, “but at the same time, it felt like an open space where anything could happen. That was really beautiful. It was not like ‘metal guitarist and metal drummer look for metal bassist,’ you know?”

One thing they agreed on right away was their desire to steer away from the sort of techno that was taking off in Germany at the time, setting the stage for seminal labels like Kompakt. While they certainly listened to electronic music, St. Werner and Toma also bonded over everything from the noise outbursts of Merzbow to the electroacoustic experiments of INA grm.

This all-bets-are-off attitude informed their earliest sessions at Toma’s apartment in Düsseldorf, including a timeless record from 1994 that finally saw the light of day this fall. Named after their old neighborhood, Bilk is a seamless, multi-part piece that melds analog melodies with chirpy field recordings caught outside their studio window.

According to St. Werner, it’s the first of three archival records focused on “retelling the story of Mouse on Mars.” The way he sees it, Bilk is the sound of “two dudes in a studio listening to everything they could possibly listen to, and bringing that into an idea or concept of music.”

“In a way, we’re trying to rebuild the structure—the meaning—of Mouse on Mars,” adds Toma. “If you listen to this old stuff, there’s still a connection…You can hear our hands on the music.”

To help bring things full circle, we spent a couple hours discussing Mouse on Mars’s discography over Zoom, starting with what should have been the soundtrack to a very strange movie starring…Tony Danza?

Glam

Compact Disc (CD)

When director Josh Evans—the stepson of Steve McQueen and son of Academy Award nominee Ali MacGraw—decided to make a movie about the hellish side of Hollywood, he asked Mouse on Mars to smother its sonic gaps and silences with something along the lines of Aphex Twin or Autechre. The pair’s response sounded rough around the edges but relatively ambient compared to the rest of their catalogue.

Evans didn’t see it that way; it was a little too outré for his taste, enough to warrant shelving the score and recording his own collection of what St. Werner charitably describes as “cheesy synthesizer crap.”

“I think [our] music had more personality than the movie,” he explains, “so it was a bit out of balance—too idiosyncratic and intense…In a way, we weren’t even doing a traditional score. We were reshooting the movie in sound.”

Niun Niggung

“All this ultra-yuppie stuff was going on in the ‘90s,” says St. Werner, “but it was also a moment of real self-empowerment. You could reinvent your life every day without having an agenda…It was a time where you had hope.”

This prevailing sense of freedom spilled over into the first album Mouse on Mars recorded at their newly built St. Martin Tonstudio, a cavernous space in a former liquor factory set aside for artists in Düsseldorf. As their loft mate painted bold pieces within earshot, the duo embraced their wildest ideas without the pressure of making unreasonable rent payments or wrapping a rigid pop record within a set timeframe. If anything, the late ‘90s was a period that rewarded progressive music and restless beats—everything from the brassy outbursts of “Yippie” to the wobbly rhythm section of “Pinwheel Human.”

“People like us—people who produced everything in their home—could have a record that went into the charts back then,” says St. Werner. “It was a time driven by euphoria,” explains St. Werner. “Not a euphoria that made you hysteric—a euphoria that gave you the confidence to continue doing your own thing.”

Niun Niggung was so well-received in the UK it landed at the top of The Wire’s year-end list and earned hyperbolic accolades like the pull quote that was plastered across the shrink wrap of its CD pressing.

“Someone called us the ‘inheritors of Kraftwerk’s mantle’,” recalls St. Werner. “Andi peeled off that sticker and put it on our live mixing desk so we would laugh about it every time we did a show. What a weird, very British idea of placing us within music’s history. Or at least their perspective of it.”

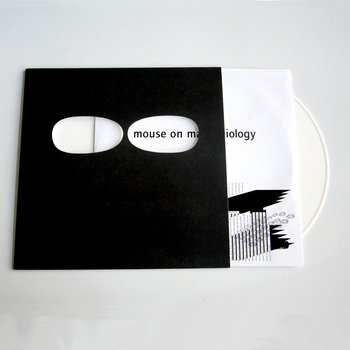

Idiology

Vinyl LP

As the interest around their idiosyncratic recordings increased, Mouse on Mars pushed the full spectrum of extremes within their flush productions. Or as St. Werner puts it, “We hadn’t really explored that range before—how fast or slow, abstract or metric, distorted or pure, and sparse or dense sounds could be. [Idiology] was an affirmation of irresponsibility in the best sense…of investing in risk.

“Within our own limits, of course,” he adds. “We were disappointed that we couldn’t escape our own sound as much as we wanted to.”

One of the many distinct ingredients within Idiology is the distortion that drives immediate standouts like the noise-punk single “Actionist Respoke.” Ryuichi Sakamoto’s reps actually reached out to the duo around this time to ask if they could produce a similar beat for the composer. Since it was more of a work-for-hire situation than a proper collaboration, they politely declined and were surprised to hear a similar technique surface on Sakamoto’s next pop record.

“They basically reconstructed the beat from ‘Actionist Respoke’,” explains St. Werner. “It made me laugh because it was so cleanly distorted. I thought, ‘Oh God, they put [the song] through some distortion device and obviously used pedals or plugins.’”

And therein lies one of the things that sets Mouse on Mars apart from many other producers—their obsession with how a sound is made, not just the final product. It’s an attention to detail you can’t really teach; it’s just something you naturally do.

One person who understands this on a deeper level is Matthew Herbert, a longtime friend and occasional collaborator (see: the slamming DJ’s Collapse reunion “Double Gum”) who lent some piano lines to Idiologyand must have appreciated their tactile use of everything from a ring modulator to a mixing desk.

“Sound itself is a vehicle,” says St. Werner. “It’s constantly driving and moving [us].”

Radical Connector

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Critics often called Radical Connector Mouse on Mars’s pop record when it was released two decades ago. One reason was its more prominent use of mangled yet melodic vocals. Those duties were split between longtime drummer/live band member Dodo NKishi and Niobe, a recent signing to Soniq, the label Mouse on Mars founded with Frank Dommert in the late ‘90s.

According to Toma, this shift reflects the heady R&B they were listening to instead of electronic music, especially Rodney Jerkins’s essential sessions alongside Brandy.

“They reminded us of when My Bloody Valentine did Loveless,” explains St. Werner. “It was like turning a knob took things one step further—a complete change of sound.”

Top 40 tendencies aside, one thing remained the same within the Mouse on Mars universe: how they build highly processed beats and heat-seeking hooks on top of so many tactile, warring elements.

“We are a granular kind of band—always taking everything apart and trying to understand each particle of sound,” says St. Werner. “I know people wouldn’t relate what we do to [Iannis] Xenakis, but our understanding of music is much closer to somebody like him than the Beatles or another band in a studio with instruments.

He continues, “Even if we played an instrument, we would sample it from different sides, chop or filter it, and place it in juxtaposition to something else that had been processed or altered.”

Varcharz

Compact Disc (CD)

When Zomba’s growing label group swallowed Rough Trade Records in 2000, Mouse on Mars suddenly found themselves in the same multiverse as Britney Spears and Backstreet Boys. “Which was kind of weird,” admits St. Werner, “but we didn’t mind because we still had [creative] freedom and nobody was trying to change our path.”

The duo’s can-do attitude took a sudden turn in 2002 when BMG swooped in and bought the entire business for $3 billion. Since they still had an option for one more record with Zomba, and weren’t the least bit interested in working with a behemoth like BMG, Mouse on Mars gave their new overlords an ultimatum: pay us our advance and you won’t have to release the unruly racket that is Varcharz.

It worked. After about two weeks of contentious talks, BMG terminated Mouse on Mars’s contract and gave them the freedom to go their own way. After hearing that Mike Patton was interested in working with them, the group jumped at the opportunity to place Varcharz’s fidgety productions on Patton’s Ipecac Recordings imprint.

As for why they were okay with Zomba but unwilling to bond with BMG, St. Werner says the former was more of a necessary evil since they needed a distributor, and the latter felt like everything that was wrong with an increasingly consolidated music industry. “Merges didn’t just mean a new music label anymore,” he explains. “Merges were more like a conglomerate—a corporation…Not for the love of music; for the love of making money.”

Parastrophics

As futuristic as their previous records sounded, Parastrophics was the first time Mouse on Mars fully embraced computers and the “millions of plugins” software companies were trying to get them to co-sign.

“As strange as it sounds, Parastrophics was the affirmation of the digital era for Mouse on Mars,” says St. Werner. “Before the computer screen was just one part of a much larger setup—its control center. Now the screen was basically the studio.”

The only problem with the “physical, flashy and fat” productions on Parastrophics was their saturation level. Much like a photographer eager to use the filters on their iPhone, Mouse on Mars were left with red-blooded recordings that sounded almost too distorted. An engineer was the first person to point out its many peaks. Since the duo weren’t about to scrap their sessions and redo everything, they decided to embrace its eccentricities instead.

“We had a few friends who complained that it sounds strange and not as warm,” says St. Werner, “but people generally dug it. It’s a weird record, but it worked. In the end, it was consistent—both how it sounded and the story we told through the record.”

Like-minded peer Uwe H. Schmidt (aka Atom™) was especially supportive of its coarse recordings, partly because he decided to completely forego the mastering process about 15 years ago.

“Mastering is kind of the color correction for a finished record,” explains St. Werner. “It’s the craft of reading music from a different perspective. I remember [Schmidt] said, ‘First of all, I don’t hear a difference [with mastered recordings]. And second of all, why would I have somebody change the color of what I’ve already recorded?’”

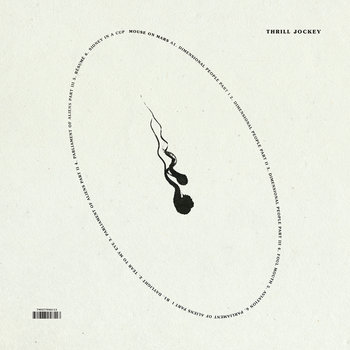

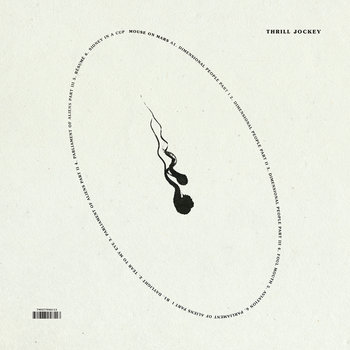

Dimensional People

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

If you’re wondering how everyone from Swamp Dogg to Spank Rock ended up on Mouse on Mars’s 11th album, you can thank German conductor André de Ridder. After knocking on the door of their Funkhaus studio, de Ridder introduced the duo to a few key musicians who were thinking of holding an event in the storied Berlin space.

“It was a guy with a beard—a very friendly guy who obviously was the bassist of the band—and two brothers,” recalls St. Werner. “They were a bit calmer…more restrained, and kind of running the band. There was also another guy with glasses who was rather tall and a bit quirkier. We thought maybe he’s the producer.”

They soon discovered the bassist was Bon Iver frontman Justin Vernon, the bosses were the Dessner brothers from The National, and the “tech bro” pulling their proverbial strings was producer/multi-talented musician Ryan Olson (POLIÇA, Gayngs, Marijuana Deathsquads). As promised, they returned the following year to hold a free-wheeling festival with more than 80 artists. Many of which stopped by Mouse on Mars’s studio with no plans other than to hit record and see what happens.

Building on that brash spirit was Vernon and Dessner’s Eaux Claires festival in Wisconsin the following year, which included a performance by Mouse on Mars and featured such “Artists-in-Residents” as Sam Amidon, Jenny Lewis, and Phil Cook. It also led to loose sessions at Vernon’s own studio. Much like the Berlin recordings, they followed a certain key and rhythm—“a very basic harmonic structure,” according to St. Werner—but lacked any other rules.

All of these moving parts could have created a rather chaotic record; Dimensional People is the opposite however, a series of surprisingly focused suites that Toma compares to Pet Sounds. Not in tone or song types so much as approach.

“For me, [Pet Sounds] is the perfect pop record,” he says, “a documentation of the recordings itself, giving you a view inside [the studio].”

“It’s hard to sum it up,” adds St. Werner, “but Dimensional People was a record where we trusted other people and didn’t have to produce every sound ourselves. To me, it somehow connects to Paeanumnion—our orchestral record—because it was a symphony of sounds that we did not have to craft completely.”

AAI

Compact Disc (CD), 2 x Vinyl LP

If Parastrophics is the byproduct of Mouse on Mars beginning to toy with the raw potential of digital music, AAI is the point where they let technology speak for itself. Literally, it stands for “Anarchic Artificial Intelligence” and stems from conversations with former SoundCloud programmers (Ranny Keddo, Derrek Kindle), an AI tech collective looking to collaborate with musicians (Birds on Mars), and thought leader/English professor Louis Chude-Sokei.

St. Werner says, “We liked the idea of artificial intelligence being more than just a problem solver finding the most efficient way of solving something that a fucking human being could solve as well. That doesn’t sound interesting. That doesn’t sound like the future. You’d think the future would come up with things that would seem unimaginable until now.”

To put this concept into practice, text and voice from Chude-Sokei and DJ/producer/machine learning engineer Yağmur Uçkunkaya were used to make an AI model and encourage an eerie form of speech synthesis. In other words, they gave the robots a voice and let them speak the way a sentient instrument would.

“It’s amazing that Louis trusted us,” St. Werner says with a smile, “because we could have ordered millions of pizzas with his voice or sent death threats to the dean of Boston University, where he is a professor.”

Instead, they created their most ultra-modern album yet—a fluid exchange between living, breathing instruments and music with a mind of its own.

“It’s a very digital record,” says St. Werner, “and it sounds great. There is no distortion. Ten years after Parastrophics, we finally mastered the digital domain.”