To tell the story of the legendary Swedish death metal band Dismember, one must first tell the story of Carnage. After releasing a series of raw but promising demos in 1988 and 1989, drummer Fred Estby, guitarist David Blomqvist, and vocalist Matti Kärki dissolved the first incarnation of Dismember to focus full-time on Carnage, their collaboration with hotshot guitarist Michael Amott. The band then decamped to Tomas Skosgsberg’s Sunlight Studio to record their 1990 debut Dark Recollections.

That album stands as one of the earliest examples of what would become the signature Stockholm death metal sound. With Dark Recollections, Carnage had literally consumed Dismember. “There was plenty of overlap,” Estby says. “We needed more material, so we said, ‘Let’s grab some Dismember songs. They’re not going to be used anyway.’”

There’s an alternate timeline where that’s the totality of Dismember’s legacy, but a Liverpudlian hand of fate intervened. “When we recorded the Carnage album, [Amott] stayed with my parents and me, and I got him a job where I worked, so we were working in the same place,” Estby recalls. “But then, when the Carnage record was over, we had hit the goal, so he moved back to the southern part of Sweden where he’s from originally. We were like, ‘Alright, talk soon,’ and then I didn’t hear much. And suddenly, he’s in Carcass.”

With Amott joining the scowling UK death grinders, Carnage was no more. The door was open for a Dismember reunion—just a few months after they had broken up. In 1991, the band would release Like An Everflowing Stream, a Swedish death metal debut rivaled only by Entombed’s foundational Left Hand Path. A vibrant, internationally recognized scene would soon spring up in its wake.

“It was a perfect storm and a perfect timing,” Estby says. “You could actually feel it. When you knew that Unleashed had recorded an album, Grave was about to record an album, we were recording an album, and Entombed were about to record their second album, then you realized, ‘Wow, stuff is really moving here.’”

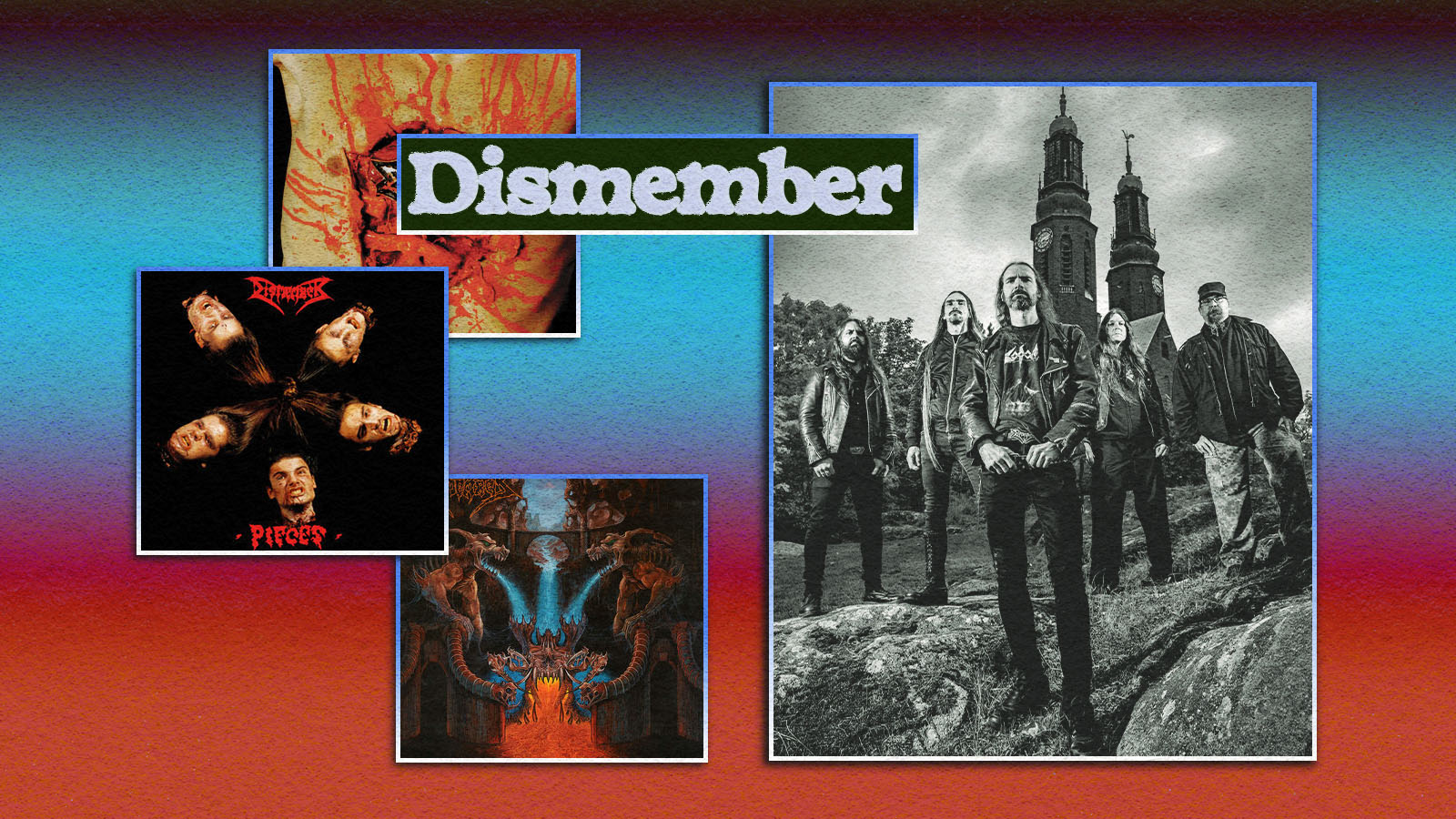

Dismember would go on to become one of the most revered Swedish bands of the ’90s and a death metal powerhouse well into the 2000s. They entered a long hibernation at the turn of the 2010s, but in 2019, they reunited for a string of festival dates. Estby sounds reenergized by the prospect of carrying Dismember forward into the ’20s.

“It was pretty cool to go back in October of 2019 and rehearse for a whole week before we played our first shows,” he says. “It was a lot of fun and really good to see the guys again and hang out. It was like we hadn’t lost 10 years. It was more like, ‘Oh, this feels the same.’ We’re laughing at the same things. We’re still the same people. No one has really changed.”

Estby recently took some time away from a career-spanning remaster campaign to walk us through the Dismember discography.

Like An Everflowing Stream

Left Hand Path may have been the record that launched a thousand young Swedish bands, but the buzzsaw-blade opening riff of “Override of the Overture” must have sold at least a thousand Boss HM-2 pedals. Dismember’s guitar sound, as captured by Tomas Skogsberg on Like An Everflowing Stream, remains one of the all-time purest embodiments of Swedish death metal. (Entombed’s Nicke Andersson played most of the leads on Stream, ironically lending Dismember some of the Maidenesque melodicism that would help separate them from their Stockholm kin.) The band’s demo years—and their brief Carnage interlude—had set them up to strike hard right out of the gate. Stream was a new death metal classic, even if the band didn’t quite understand it at the time.

“Just when the album was released, we went on a very short part of Morbid Angel’s European tour,” Estby recalls. “And we didn’t know how to tour yet. We were pretty fresh and green. We were like, ‘Oh, this is weird, what’s going on? We’re living in a very small RV with a German driver, with all the equipment in the same car, so we barely have a place to sleep.’ We were like, ‘OK, this is touring. Maybe it didn’t go that well.’”

Estby returned to his parents’ house after the tour, where he received a phone call from Nuclear Blast that he remembers vividly to this day. An elated rep from the sales office told him that Stream had sold 21,000 copies in its first month—huge business for an independent metal label, let alone for a debut album by a band from Sweden.

“I heard the next week that the label weren’t that happy that someone from the label called the band member and told them exactly [how many copies],” Estby laughs. “So, they were like, ‘Oh, he’s exaggerating.’ To this day, I don’t know what was true or not, but it got me excited. I was like, ‘Whoa! So, there is stuff happening! People are listening to this album and liking it.’”

Indecent and Obscene

Dismember followed Like An Everflowing Stream with 1992’s Pieces, a strike-while-the-iron-is-hot EP that they recorded in two nights. Their proper sophomore effort was 1993’s Indecent and Obscene, a densely layered killing machine that saw the band simultaneously pushing brutality and complexity to the fore. It was a mixed experience for Estby but a crucial chapter in the band’s evolution.

“For Indecent, I wanted to go more extreme when it came to the arrangements,” Estby says. “Not to be more technical, but maybe have more stuff in there. In hindsight, maybe it was a little bit too much. We could have done a couple of more songs out of all the riffs on that album. But the songs that were good, they stick out, which I love.”

Massive Killing Capacity

“We were still recording with Tomas [Skogsberg] at Sunlight Studios, and he was very adamant that we should do a pre-production,” Estby says of 1995’s game-changing Massive Killing Capacity. “Indecent, we all kind of agreed that it was a little bit too much on certain songs, too much stuff happening. So, he really wanted to make us control the sound more, and it was easier for him to make us sound good, in his opinion, if we slowed it down a little bit.”

The slower-on-average tempos on Massive Killing Capacity helped two crucial elements of Dismember’s sound emerge: groove and melody. The songs here are among the band’s catchiest, and Kärki’s mid-range bellow renders their searing, war-is-hell lyrics almost fully legible. In a pivotal year for the more flamboyantly melodic Gothenburg-style death metal, Dismember were happy to provide a more muscular alternative. (For his part, Estby doesn’t recall a rivalry with Gothenburg; he points instead to the encroachment of Norwegian black metal as the era’s primary scene schism.) Massive Killing Capacity also helped Dismember shed some of the lingering comparisons to their pals across town.

“There was a very long time where people called us Entombed clones, just because we were the only band except for Entombed who used the HM-2 and actually embraced that sound, and we were really close friends,” Estby says. “So people were like, ‘You’re just copying Entombed.’ And it’s like, ‘No, we’re not!’ Because we’re more melodic. They would never have certain riffs that we had.”

Death Metal

By 1997, Estby had been working as an assistant engineer at Sunlight for several years, but Death Metal was the first Dismember album he took the lead on as producer. (“It’s kind of my first baby,” he muses.) Its Venom-inspired title was at once a response to the Norwegian black-metallers who had taken to referring to Swedeath as “life metal” and a reaction to the simpler, groovier Massive Killing Capacity.

“I was really hungry to get a really good death metal album out,” Estby remembers. “Especially since this whole black metal thing, we were like, ‘We’re not gonna go down this slower path, like with Massive. We should go back to our roots. That’s what we do best.’”

Songs like the martial “Of Fire” and “Let the Napalm Rain” characterize an album whose maxed-out, pedal-to-the-metal sound still feels provocative today. Death Metal is certainly an extreme listen, but its canny melodic sophistication builds on Massive while recapturing the raw verve of the band’s earliest material. By any measure, it’s a staggering highlight in the Dismember discography. Estby hopes the new remaster will make that even more evident.

“It’s still my favorite Dismember album, because I like the songs,” Estby says. “But there are certain things that I probably could have done better as a mixing engineer. I worked it, I pushed it, and I think it’s cool that it’s so extreme, but we’re going to look at it now. I’m not a fan of remasters that completely change the whole feeling of the album. I think that’s pretty dangerous, so you have to be pretty careful. But I think, so far, so good.”

Hate Campaign

“That’s the only album where a couple of the songs, if I hear it, I’ll be like, ‘Oh, I remember this,’ but a couple of the songs I’ll be like, ‘Wait, that sounds like us. What’s this?’”

Estby doesn’t have much higher praise than that for 2000’s Hate Campaign, the first Dismember album to be recorded outside of Sunlight. Estby was working down the street at Das Boot Studio, and he wasn’t as familiar with their equipment as he would have liked to be at the time of recording. That unfamiliarity, combined with lineup turmoil, canceled tours, a lack of rehearsal time, and a general down period for death metal worldwide, made Hate Campaign the weakest Dismember album, at least in Estby’s view. Yet it was a watershed moment in reestablishing the terms on which the band could continue to exist.

Where Ironcrosses Grow

After Hate Campaign, Dismember took a nearly four-year break, easily the longest in the band’s existence up to that point. Estby took a job as a floor manager at a gym in Stockholm. It wasn’t capitulation; he just needed to put food on the table.

“I had kids. Matti had kids. We didn’t get a lot of tour offers,” Estby says. “It felt like death metal was not kicking the bucket, but it’s not anything we can live off of—even though we didn’t really in the past, either. But you could go on a 10-week tour and come back and then do some work. But now it was up in the air with everything.”

In 2003, interest in the band started to grow in countries that were undergoing new waves of death metal, among them Italy, Spain, and Germany. Dismember agreed to play some shows in those territories, and things were feeling good enough that they started work on Where Ironcrosses Grow. They all knew it would have to be different from Hate Campaign. “I told David and Matti, ‘Okay, let’s do a new album, but now we have to be way more critical of ourselves,’” Estby says. “‘If we can’t come up with really good, catchy songs like we used to, then we’re scrapping it until we do. We’re not going to compromise this time.’”

The band recorded Ironcrosses at the swanky, grant-funded Swedish Artists’ and Musicians’ Interest Organisation (SAMI) Studio in Stockholm, and the vibe had completely flipped since the Hate Campaign sessions at Das Boot. The album was a huge improvement as well. “I was really happy with the songs,” Estby confirms. “I felt like we got it better. We rehearsed more. Everyone was in and really hungry for it.”

The God That Never Was

Encouraged by the reception for Ironcrosses, Estby and his bandmates rededicated themselves to the Dismember business. “It was getting better and better,” he says. “Again, we did this thing where we were like, ‘Let’s put the band in the front seat again. Let’s try to make a living off of this.’ We were realizing we could tour, we could play shows, and we could get decent payments, and people were buying more merch, we realized.”

But alas, nothing gold can stay. Integrating a full-time gig as a live musician into family life proved taxing, and the tours in that period—including a dream jaunt with Entombed, Unleashed, and Grave—were marred by cheapskate promoters and poor planning. Estby found himself mentally frayed and at wit’s end. He left the band in April 2007, almost exactly a year after the release of The God That Never Was. Estby likes the album, but he didn’t have much to say about it—understandable, given the circumstances. My take is that it’s one of Dismember’s very finest, powered by some of the strongest melodies of their career. The album’s closing track “Where No Ghost Is Holy” is a top-five Dismember track and the full realization of their “Iron Maiden death metal” approach. To date, it’s the last Dismember song featuring Estby.

Dismember

The remaining members—Kärki, Blomqvist, plus newcomers Martin Persson, Tobias Cristiansson, and Thomas Daun—forged ahead after Estby’s departure. They recorded a self-titled Dismember album in 2008, and Estby doesn’t sound like he’s just being diplomatic when he sings its praises.

“I love the album I’m not on,” he enthuses. “Thomas, who played drums, [is an] excellent drummer. I’ve recorded him for other bands. Dismember is a great album with great production, too. It’s fucking brutal, and I love it. It has all the essence of Dismember. It’s death metal, but with a really good sense of melody.”

The self-titled album may not end up as the final chapter in Dismember’s discography. The reunited band hasn’t recorded anything new just yet, but it’s something that’s on all their minds.

“We’re talking about making new music,” Estby confirms. “The question is when. As of right now, because of the pandemic and all that, this year was only honoring all the shows that were booked in 2019 and 2020. So, we got those done, and of course, the way metal festivals, especially in Europe, work now is as soon as they’re done, they’re already selling tickets for next year’s edition. So we have a couple coming up, which is gonna be really fun. But we’re also thinking about recording more.”