If “cowboy” and “punk” are both words with nebulous and contested meanings, cowpunk has that problem squared.

On one hand, as a genre tag, it’s self-explanatory: punk rock + cowboy music/country. It started popping up in dictionaries around 1979 as a general descriptor of music blending the two. Coalescing around a specific group of bands from the first-wave L.A. punk scene, it crested in the early ‘80s with the cult success of bands like The Gun Club and the punk-to-country dabbling of X, The Blasters, The Knitters (a one-off collab between the two), and Social Distortion.

On the other hand, cowpunk’s lack of specificity has led some artists tagged with it to bristle. “Part of the problem stems from ‘psychobilly’ and ‘cowpunk’ being used interchangeably,” says Jeff Smith, leader of the Austin/San Antonio band Hickoids, who are typically lumped in with the latter.

Whereas adjacent genres like rockabilly/psychobilly possess an aesthetic purity permanently dialed to the ‘50s, and outlaw country has a pedigree in red dirt music, “hanging a catch-all tag on the bands [labeled as cowpunk] might be viewed by the musicians involved as wrong or lazy. The problem is that the terminology tends to cheapen the described music due to its overuse, even though it can be useful and meaningful,” Smith continues.

Whether one embraces or despises the term, it’s a fact that cowpunk has enjoyed a long life as a floating signifier enthusiastically adopted by bands hoping to quickly convey a hybrid sound, flexible enough to find adherents throughout the U.S. and beyond.

Here are some major touchpoints from the cowpunk catalog to be found on Bandcamp, from genre originators, to fast followers and regional spin-offs, to artists proudly self-identifying with the genre today.

Wherever one lands on the term cowpunk, Los Angeles group The Gun Club are canon in the genre. During their 1979 to 1996 run, they pioneered a novel mix of punk, blues, rockabilly, and country, all smelted in the singular style of bandleader Jeffrey Lee Pierce. His haunted, gauzy vocals and cryptic, gothic vibe earned them a cult following across the U.S. and Europe, where they blazed a tour trail that would be followed by other bands walking similar stylistic paths in the years to come. Seminal albums Fire of Love and Miami, in particular, showcased Pierce’s soulful, bluesy vocals and the band’s tendency to blend punk rock intensity with twangy guitars and country-inflected rhythms.

A close associate of Pierce, Texacala Jones made her own distinctive mark on the incipient cowpunk genre with her band Tex & the Horseheads, especially the 1985 album Life’s So Cool.

Jeff Smith of the Hickoids, who recently hosted Texacala Jones for an event in San Antonio celebrating the release of David Ensminger’s new book, Roots Punk, notes that even in its earliest, purest form, “cowpunk” was a grab bag of styles outside of just country and punk: “All of the early bands of that ilk brought something a little different to the table in addition to punk edge and country flair…Gun Club brought goth, swamp, and blues; Tex & the Horseheads brought goth and glam; Screamin’ Sirens was a girl group with a pop sensibility; [and] Blood On The Saddle brought bluegrass and mountain music.”

L.A. band Blood on the Saddle was directly influenced by Gun Club. Guitarist and sole constant member Greg Davis saw the latter open for the Cramps in 1981 and was immediately inspired by their incorporation of slide guitar into hard-driving, punk-adjacent tunes. Blood on the Saddle’s early style co-opted bluegrass and traditional country and western into punk similarly to the way The Gun Club had done with Delta blues, and X with rockabilly.

Davis vocally despises the term “cowpunk,” but among his contemporaries, his extremely fast bluegrass-style fingerpicking is the most obvious example of the stylistic congeniality between Americana technique and punk speed. Check out 1987’s SST release Fresh Blood, the third and final album by the original lineup of Blood on the Saddle, for a particularly blistering example.

Another band often mentioned on the short list of canonical cowpunk is Meat Puppets, who formed in Phoenix in 1980 and helped shape the harder/faster/noisier zeitgeist of early hardcore with their self-titled debut album on SST two years later. Their 1984 follow up, Meat Puppets II, is quintessential cowpunk, tempering the frenzied shredding of their earlier work with country inflections like intricately finger-picked melodies, as well as the psych and garage flourishes that would shape much of their later discography. Obviously country-influenced tunes like classic road song “Lost” stretched out the track lengths and slowed down the tempo, but only slightly.

Meat Puppets toured II across almost 40 cities with Black Flag in spring 1984, spreading their brand of cowpunk widely and finding a sometimes awkward fit on hardcore bills. 1985’s Up On the Sun is tighter, slower, cleaner, and less stylistically indebted to country than Meat Puppets II, but uptempo tracks like “Two Rivers” represent a throughline from hardcore and cowpunk to the band’s later stylistic evolutions.

The Nervebreakers from Dallas are not typically lumped in with cowpunk. This is partially because they preceded the aforementioned L.A. bands, and partially because the country influences are less obvious on their recorded material, though they cut their teeth in the early ‘70s by covering George Jones. The band mixed roots-y, country-inspired melodies and lyrics with early punk in a way that positions them as a precursor, if not early exemplar, of the genre, according to Smith. “It’s one of those things, like electricity or the automobile, where there’s a lot of people who say, ‘Hey, we’re going to mash this up’ simultaneously, and then some of the projects get off the ground, some of them don’t.”

One of the few American bands to open for both the Ramones (at the Electric Ballroom in July 1977) and the Sex Pistols (at the Longhorn Ballroom in January 1978), tracks like “My Girlfriend is a Rock,” with its driving rhythm and twanging guitar, showcase the Nervebreakers’ ability to bridge the gap between punk and the traditional sounds of American country.

Jeff Smith moved from Houston to San Antonio, Texas as a kid and was onboard with first-wave punk well before the Sex Pistols even had a record through his avid readership of NME and Melody Maker. After the Pistols played in San Antonio on their ill-fated 1978 tour, he says, local musicians took up punk styles en masse and simultaneously embarked on exodus to Austin, where the recently opened Raul’s would become a regional lodestar for the nascent genre. (Smith himself moved to Austin in 1982, and started Hickoids soon after.) The timing is roughly contemporary with the L.A. cowpunk bands, but Hickoids were more directly associated with the early ‘80s Austin punk scene that coalesced around the converted frat house OAF House.

Having grown up in San Antonio, Smith was in a unique position to put his own, un-self-serious spin on mashing up punk and country. Reflecting on San Antonio in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, Smith remembers “a lot of working country bands, working honky-tonk bands. Austin, not as much…From the Hickoids perspective, we appreciated old country artists, [but] we had very little respect for contemporary country. We were poking some fun at it, for sure.”

Hickoids had been rehearsing for less than three months when they opened for Black Flag and Meat Puppets at long-defunct San Antonio venue Villa Fontana in March 1984. Cowpunk was a tag attached to them early in their career, one Smith distanced himself from over time.

“I don’t know when I first heard the term, just like I’m sure people don’t know when the term rock ‘n’ roll was coined,” he reflects. “I would say generally it was applied from outside, and it became something convenient to hang your hat on, no pun intended.”

After psychobilly spiked in popularity following the success of Dallas’s Reverend Horton Heat, Smith says the term cowpunk was watered down to the point of meaninglessness. “At that point in time, I kind of soured on the term because to me it evoked an image of a three-piece band: a standup bass player with a chain wallet, train beats, and every song is about drinking…a fairly unimaginative take on things.”

That said, Hickoids still get pegged with the term today, and offer a unique Texas punk and country spin on it. After an initial run lasting from 1983 to 1991, they’ve since reformed and now play 40–60 dates a year, with Smith also spending his time on his regional roots-focused label Saustex and the Corn Pound, a record shop, recording studio, and event space in San Antonio.

Another band straddling the border between country and punk is early ‘80s Nashville outfit Jason & the Scorchers. As they lean more toward the former, they’re usually not tagged as cowpunk, but they’re a clear antecedent of bands in the region who’d more explicitly roll punk attitude and tempo into their music, with a sound that does contain some of punk’s rebellious energy and distorted grit.

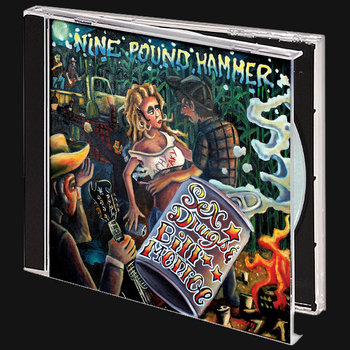

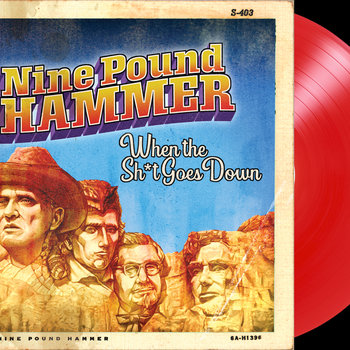

Scott Luallen of Kentucky band Nine Pound Hammer recalls stumbling upon an early Scorchers record and taking it as a sign that his own nascent cowpunk project was on the right track. “We didn’t know [the L.A. cowpunk] stuff,” Luallen remembers. “We had stumbled upon a Scorchers record. We were already kind of doing that, doing ‘Folsom Prison’ and rocking it up. And then we heard that [Scorchers record], and we’re like, ‘OK, yeah, this is what we want to do…’ But we really liked the Ramones, though. We’ve always been more punk than the Scorchers, I mean, way more.”

Compact Disc (CD)

Like Smith, Luallen and his high school friend and bandmate Blaine Cartwright (later of Nashville Pussy) were around for the first wave of punk. Growing up, Luallen says, “country music was just in the background all the time,” and it was a short leap from the rebellious Johnny Cash tunes he’d fall asleep to as a kid to the brash, sped-up eighth-note basslines of The Ramones and Sex Pistols songs he heard on AM radio in Owensboro, Kentucky when he was a little older.

By the time Nine Pound Hammer started, cowpunk felt like a natural fit. In addition to wearing their influences—ranging from The Ramones and Dwight Yoakam—on their sleeves, Luallen adds, “I’m from Kentucky—I sound twangy on top of it.” Luallen grew up with a cornfield in his backyard, and Cartwright grew up in a trailer park. Luallen describes their background as a “suburban redneck deal where we have one foot in one world and our other foot in the other world,” a natural corollary to the admixture of ostensibly urban punk rock and nominally rural country music. “That’s just what we’re good at, it’s natural, and it’s real. We’re not writing about shit that we don’t know about.”

Compact Disc (CD), Vinyl LP

Like the Hickoids, Nine Pound Hammer is coming up on 40 years as a band, and still touring. The kinds of bills they play reflect the odd congruence between punk and Americana that has contributed to cowpunk’s staying power.

Last year the band played two festivals on the same fairgrounds in the Netherlands in two weeks: Pitfest, where they shared the bill with hardcore and metal bands like Cro-Mags and Hatebreed, and then Roots, Ribs, Brews Fest a week later, which zeroes in on Americana and its European offshoots. The band fit in at both fests, Luallen says, in part because of the natural overlap between country and punk. “It’s the attitude, you know? Rebellion, anti-authority. It’s the same themes: a lot of drinking and debauchery and raising hell. You know, all punk rockers love Johnny Cash.”

Luallen uses cowpunk as his go-to descriptor for that reason, noting that he later became aware of bands like Gun Club and Tex & the Horseheads, following the DIY tour trails of the former, but not until after his own band had honed in on their sound. “Nobody really plays it like we do, but that’s the whole thing. This is our version of it. You know, Ramones, Johnny Cash hybrid: cowpunk. That’s what it is. It’s real simple.”

The same tour network traveled by Gun Club and Nine Pound Hammer was also well-trodden by legendary Portland punk band Dead Moon. They definitely weren’t a cowpunk band, but the band immediately preceding Dead Moon’s formation was.

Range Rats were a relatively short-lived project by Dead Moon’s Fred & Toody Cole, who each had a long pedigree of previous work before Dead Moon hit it big as they both turned 40. Fred moved from garage to punk after his band King Bee opened for The Ramones at Paramount Theater in 1977, almost immediately forming punk trio The Rats in response, with Toody on bass.

“We’re just all standing backstage, and Fred was just blown away by the energy of the Ramones,” Toody recalls of the gig, 46 years later. “For him, that was it. Even though we were in our early 30s and most of the kids that were playing punk rock were really, really young… but hey, what the hell?! Yeah, let’s go for it.”

The Rats lasted about three years and gave way to Fred’s short-lived, straight-ahead country band Western Front, which eventually led to the cowpunk coalescence of Range Rats. Toody Cole says they self-identified as cowpunk at the time, though they weren’t exactly plugged in with the contemporary LA bands exploring similar territory; she’d only become familiar with Gun Club years later, as Dead Moon went to Europe with the same tour manager.

“Both of us loved listening to old country stuff for the longest time,” Toody recalls. “Patsy Cline, Johnny Cash, Hank, and all that. It’s just weird how music seems to gravitate toward the same genre in cities all over, at almost the same time. And this is before the internet, when everybody’s sharing what everybody else is doing… Everybody was touring at the same time, so you just kind of missed each other, left notes backstage for people and that kind of stuff.”

Toody recalls other bands she considers cowpunk-adjacent in the Portland area, like The Rebel Kind and True West. She and Fred also shared bills with pre-Rank and File group The Dils from Southern California, who played Portland often as they’d tour up and down the West Coast.

But Range Rats is a standalone time capsule in the Coles’s musical journey. It was recorded in 1985 after they’d done an extended tour of rural Nevada and northern California mining and ranching towns with no conception of “punk.” They’d cold call bars in these towns, belting out Patsy Cline covers with a Roland drum machine and a small PA they hauled around in a road-beaten VW Vanagon.

They honed their chops on this circuit; Toody was still fairly new to the bass at the time, and looks back with awe at her speed on some of the tracks. The band’s lyrical themes also exemplify the country tropes of the lonesome, roaming cowboy mixed with the experience of the tour-hardened road dogs that she and Fred already were, and would continue to be in ensuing decades.

Toody listens back to Range Rats more often than most of the Coles’s long discography, with more than a touch of nostalgia. (Fred passed away in 2017.) “When I listen to [those songs], it just puts me back at the moment. It reminds me of what was going on right then and what we were doing, what we had done, and what we were going to do.”

Vinyl LP

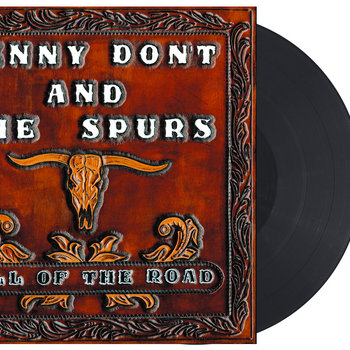

Jenny Don’t & the Spurs, arguably the standard bearers of contemporary cowpunk, share a direct link to Fred and Toody Cole via band cofounder Kelly Halliburton, who played drums in post-Dead Moon project Pierced Arrows. Vocalist, guitarist and bandleader Jenny Connors was born in New Mexico and grew up in Acme, Washington, where she started her first band. She moved to Portland in 2008 for the music scene and ended up linking with Wipers drummer Sam Henry to form the punk band Don’t (hence her moniker).

Henry introduced her to The Gun Club, which was Jenny’s first foray into what she describes as “punk-style music, but then having a pedal steel…‘Mother Earth’ is like a cowboy song.”

The Spurs started after Fred and Toody invited Connors and Halliburton, a Portland native and punk lifer who grew up seeing local bands like Poison Idea, to share a bill with them as a duo. This eventually led to them including Sam Henry in the first iteration of the band. (Henry passed away in 2022.) Their first single came out on the Coles’s Tombstone Records.

Cowpunk was and remains the best term to describe their music, says Connors. “Cowpunk, to us coming from the punk scene, it’s more like, ‘Ok, we’re punks, we’re hard-driving music, but it’s cowboy music.’ So it’s more fitting.” In addition to the tempo and decibel level, the band’s DIY ethic is another clear influence from punk in general, and the example set by Fred and Toody’s career in particular.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

That DIY ethic applies to the Spurs’s release strategy (most of their records are released on Connors and Halliburton’s label Doomtown Sounds), as well as their approach to booking tours, which recently saw them play for mixed metal, punk, and rockabilly crowds in the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

Within the U.S., their cowpunk aesthetic opens more opportunities for hybrid bills. “We can play a punk club or we can play a traditional honky-tonk,” Connors says from experience, noting a few times where they were noticeably too loud and fast for octogenarians at rural honky-tonks.

Halliburton says the mashup of punk and country was in the water in the Pacific Northwest, technically the westernmost part of the mainland United States. A diehard collector of regional music that largely hasn’t left the area, Halliburton points to the PNW’s strong country music pedigree: Willie Nelson cut his chops there, and Loretta Lynn and Buck Owens spent plenty of time in the area as well. He points to Ripcord Studios in Vancouver, Washington as a direct link between Portland’s old country and early punk scenes: some of the first Wipers and Napalm Beach records were cut on the same equipment as vintage discs by true country artists like Buzz Martin, the singing logger.

Jenny Don’t and the Spurs draws from the direct influence of Dead Moon, and their sound roughly tracks the evolution of cowpunk over time and space. The term is still actively used, a useful cypher that taps into the confluence of styles and attitudes that the original wave of cowpunk bands and their immediate precursors and followers first articulated. It’s a mesh of homegrown punk and regional roots styles that has seeped into the cultural fabric of American music, at its core a collection of hybrids.