In his 1982 book Inside The Inner City, Paul Harrison paints a picture of the East London borough of Hackney as an impoverished ghetto—perhaps the worst place to live in the UK at the time. But while poverty was rife, Hackney was also home to a flourishing Caribbean community, particularly for Jamaicans who settled there in the post-Windrush years looking for affordable housing and like-minded neighbors. Hackney became a destination for blues dances (impromptu reggae parties in derelict houses), and in the early 1980s it seemed like everyone from veteran DJs to school kids ran their own sound systems. Two such local kids, known as PJ and Smiley, set up Sir Lena Sound the same year that Harrison published his book.

“It was me and Smiley, Smiley’s twin brother Earl, and DJ Hype,” PJ recalls of their first home-built sound system. “Smiley was a carpenter, Earl was like an electrician, so he handled that side. We’d carry our own boxes and put on a dance,” the first of which took place in a church hall in Clapton on the outskirts of Hackney on November 28th, 1982. It was a reggae-heavy session and, like most sound systems at the time, they operated with just one deck and a bit of chatter on the mic between records. “But when we switched it up to two decks,” PJ explains, “it was a whole different ball game.”

As the children of Jamaican immigrants, PJ and Smiley were raised on, “everything from Bob Marley to John Holt to Yellowman.” But as kids looking for their own sound, hip-hop soon grabbed their attention. Lightning struck at a dance thrown by another local sound system called Casanova Hi-Fi. “This tune came on, and we were like ‘What the hell is this!?’” The record was “Planet Rock,” and its template of drum-machine funk played at a breakneck tempo would go on to shape PJ and Smiley’s musical direction. Soon, DJ Hype was cutting up funk breaks on two turntables, and Sir Lena became the Heatwave Sound System, with PJ and Smiley rapping and Earl as the reggae MC. “When we put on a party, it was unlike anyone else’s,” PJ explains with pride. “Other systems did reggae sounds, or they did rare groove. We’d do a bit of everything.”

A few reggae purists didn’t share PJ and Smiley’s eclectic tastes, but that didn’t deter them—“We were rare, no one else was like that. It was kind of a blessing”—and their open-minded attitude continued as they turned to production. “Our approach was [as if] we had a big Dutch Pot, and we were throwing in all the ingredients, giving it a stir and seeing what we could come up with.” They got the taste for it after winning a competition which won them a week in a community studio back in 1987. PJ laughs thinking back on record they made that week. Released under the name Private Party, “Tenants” is a far cry from their groundbreaking records as Shut Up & Dance but it gave the duo the impetus to press on. They spent the next two years honing their production skills.

In the mid-‘80s, PJ and Smiley entered dance competitions, and every crew had an outfit. “We used to up-rock and all that,” PJ chuckles, “and we’d dress up—if you look at old movies with the dancers, they all had a cane and a hat.” Harlem’s vaudeville/jazz dancers the Nicholson brothers, who took Hollywood by storm in the ‘30s and ‘40s with films like Kid Millions and Stormy Weather, were a major influence on PJ and Smiley, who carried this tradition into Shut Up & Dance, which boasted a hand-drawn logo from Smiley’s brother Michael.

Their DIY approach to releases was born out of necessity. “We had a 10-track demo, and we were sending it around to all the majors,” PJ laments, “but none of them were interested, because our music wasn’t slow hip-hop, like LL Cool J or Beastie Boys.” In response, the pair saved up some cash, quit their jobs, and on May 5th, 1989, they pressed up 500 white labels of the single “5678,” and Shut Up & Dance was born. Essentially a hip-hop record, “5678” paired a sped up Mantronix break with a loop of German drummer George Kranz’s almost Dadaist 1983 hit “Trommeltanz.” The duo rapped about their hometown, where “bad boys roam ‘pon streets.” Raw social commentary might sound like an odd choice of subject matter for a euphoric rave anthem, but as PJ explains, “‘5678 fitted with the rave scene because of the tempo. It was different, because it had the breaks.” More adventurous DJs of the day would even mix it with house and techno.

PJ admits this crossing of genres was a complete surprise. They’d never been to a rave, but Smiley’s brother had, and after hearing “5678” while out one night, he took the duo to The Dungeon, a subterranean maze of arches beneath a main road which leads from East London out to the leafy home-county of Essex. On the cusp of the ‘90s, convoys of ravers would travel miles to The Dungeon, where DJ legends in the making—including Ellis D, Judge Jules, Fabio & Grooverider—were mixing up house and acid trax mostly imported from the U.S., with a few UK records making waves.

After that, PJ and Smiley filled the trunk of their car with the “5678” vinyl and drove round to any record shop that would take it. “We’d go ‘Do you want it?’ and they’d play it and say ‘I’m not sure.’” But with the track tearing up raves and blowing up on pirate radio across London, it wound up flying off the shelves. “We’d leave them a box, and by the time we got back to the office they’d call us up saying ‘We need more of that tune!’” Eventually, they sold thousands of copies.

The next single was even bigger. “£20 To Get In”—named for their shock at the prices of raves—combined a bubbling 303 over jackin’ house beats with a funk bassline and vocals lifted from “Tom’s Diner” by Suzanne Vega. (This was a few months before DNA hit the charts with their official version.) “That happened a lot of times!” PJ exclaims. “Even ‘The Power’ by Snap—the break in that, we used that first. But they got the big up.”

Regardless, underground success continued, and the logical next step was an album. Despite the fact that their music was adopted by rave DJs, PJ and Smiley were still hip-hoppers at heart, and rap dominated more than half of 1990’s Dance Before The Police Come. The title might fit with the illegal rave scene that was sweeping the country, but it harks back to their early days of throwing blues dances. “Back then we used to find an empty house, we’d kick off the door, wire it into the mains and throw a party,” PJ explains. They were never far from their Hackney roots, with tales from their hometown featuring prominently on songs like “On A Street Level” and “This Town Needs A Sheriff.”

Another breakthrough came when they sampled a cassette of a local dancehall session hosted by Unity sound system featuring MCs Flinty Badman and Deman Rockers. “When we did our track ‘Lamborghini,’” PJ explains “there was a sample of Deman from a sound system tape. So we went to see Deman to try and get clearance for it. Obviously, Deman didn’t know nothing about this rave scene, but he was like ‘OK, cool. But what can you do for me?’”

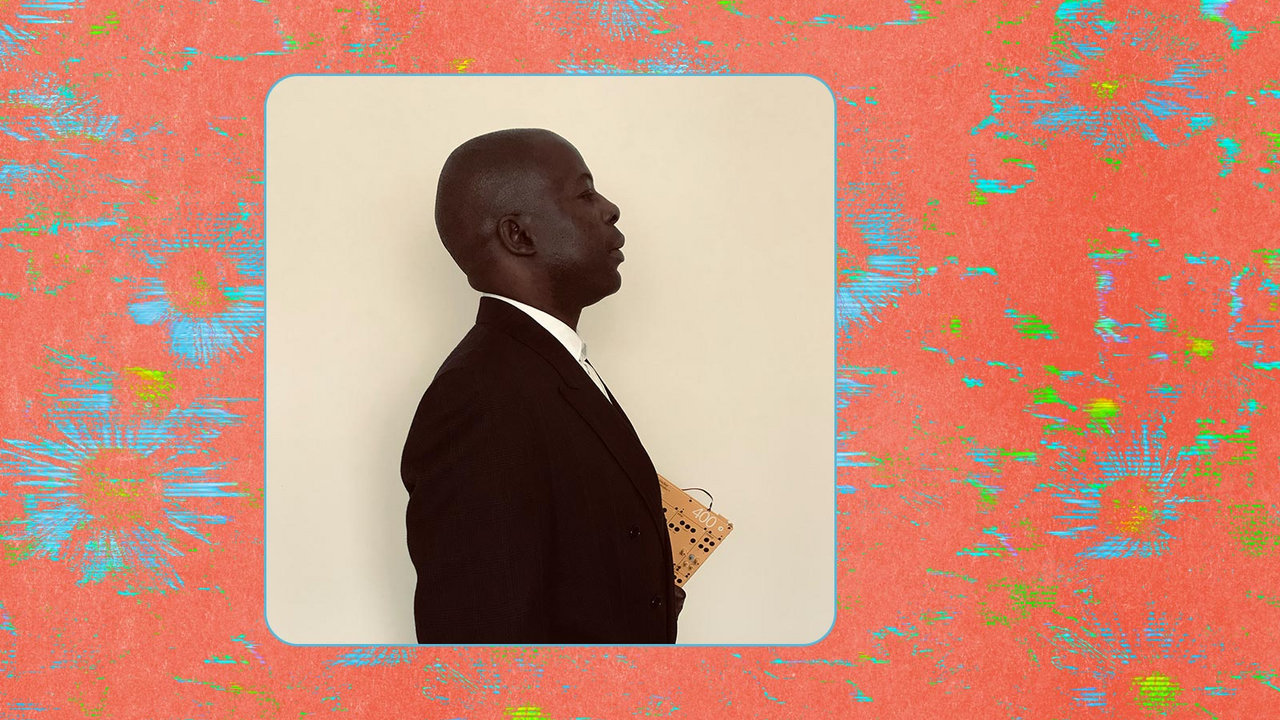

Just a few weeks before, on New Years Eve of 1989, Deman and his brother Flinty had played an all-night dancehall session. They’d been struggling for years on the UK reggae scene, and as the club cleared out and the sun rose on a new decade, they figured it was time for something new. So the timing was fortuitous: Soon, Deman and Flinty were in the Shut Up & Dance studio, where PJ and Smiley convinced them to try their usual reggae MC style over uptempo breaks. They weren’t convinced at first, but PJ assured them it would work “And it did,” PJ recalls, “so we signed them and did an album. And now I’d say it’s one of the blueprints, the foundation of what went on to become jungle, drum & bass, or whatever you wanna call it.”

With their album Reggae Owes Me Money reaching 26 in the UK charts, Flinty and Deman, aka The Ragga Twins, took Shut Up & Dance’s dub-laced breakbeat styles beyond the rave. Young folks in suburban and rural towns got their first taste of East London’s rich reggae culture, carried onto their home stereos via PJ and Smiley’s crossover production. Some of the lyrics were even recycled from previous dancehall releases: “Ragga Trip” refashioned Deman’s 1988 single “Hard Drugs” over a rolling hip-hop break and a squelchy 303 bassline, making this one of the few anti-drugs songs of the rave era. Not that most of their new-found audience would have known; the Twins’ broad use of patois still confuses some listeners to this day, especially their iconic battle cry “RAGGA TWINS DEH BOUT” on the ur-ragga-rave anthem “Spliffhead.” Many assumed they were saying “Ragga Twins step out,” which even became the title of a 2008 retrospective released on Soul Jazz. But it literally translates as “Ragga Twins, they’re about.”

While much of the album is closer to hip-hop than the proto-jungle you might expect, four tracks stand out with their house-tempo breaks and hands-in-the-air synths over bone-rattling basslines. In fact, the overlap between reggae sound systems and raves was the need for huge subby speaker boxes, demonstrated perfectly on “18 Inch Speaker” which bridged the gap between UK reggae legend Jah Shaka’s ’80s productions and the shape of jungle to come.

Curiously, neither of the Twins feature on “18 inch Speaker,” and PJ confirms their input on the album was strictly vocal. The decision to release these instrumentals under the Ragga Twins name was “all part of the same concept,” PJ says. “It was reggae done differently.” Almost overnight, Deman and Flinty became the faces of the Shut Up & Dance camp—which suited PJ and Smiley, who wanted to focus on their work in the studio. “Otherwise who’s gonna make the music?” PJ reasons. “So we’d send the Ragga Twins out [to perform at public appearances] instead.”

It’s not a massive stretch to imagine the Shut Up & Dance stable as Hackney’s answer to the great producer-led reggae and soul labels like Jammy’s, Upsetter, Stax, or even Motown. Soon, more vocalists joined the crew. Reggae singer Peter Bouncer brought the silky harmonies he’d honed on another Hackney sound system run by Jah Tubby, while Adé leant his gospel style to a handful of rave torch songs including “Free The Soul” and “Summer Breeze.” Future jungle legend MC Navigator made his debut on “Lock Up” with the Ragga Twins, and Erin who features on “The Art Of Moving Butts,” was the daughter of composer Jerry Lordan who wrote “Apache” for The Shadows, a track that would later become the ultimate B-Boy anthem in the hands of The Incredible Bongo Band.

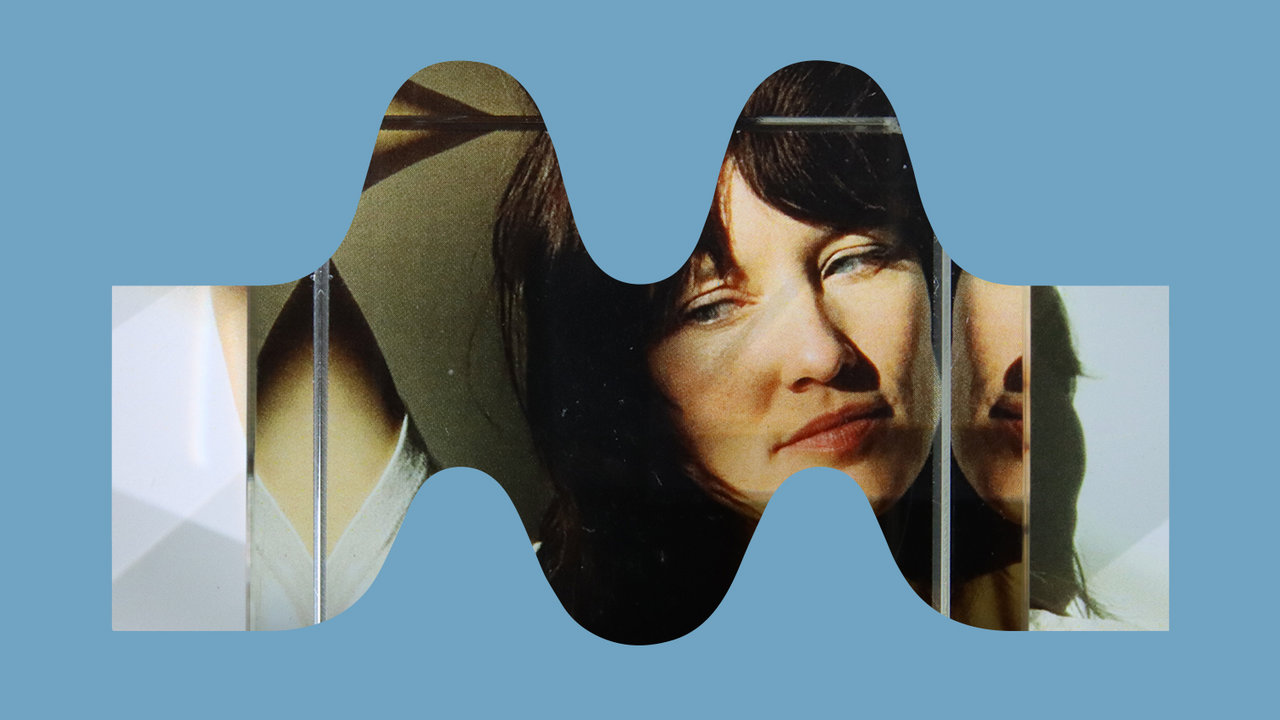

The most enigmatic name on the roster was Nicolette, a Nigerian-Scottish chanteuse who was playing in a jazz-punk band in Cardiff when she decided to head to London in search of a record deal. “I started to hear electronic music and I was really enchanted by it. I thought it sounded like jazz,” she told journalist Joe Muggs in his book Bass, Mids & Tops, “like a new kind of jazz, because jazz is all about invention and creation.” So when a friend spotted Shut Up & Dance’s advert seeking singers, Nicolette auditioned by singing Gershwin’s jazz standard “Summertime” over the duo’s trademark beats. As incongruous as that might sound, it worked perfectly, and Nicolette’s inimitable voice was soon floating out the speakers at raves across the country on tracks like “Single Minded People” and “Waking Up.”

Essentially, every Shut Up & Dance production was an experiment, and none more-so than the material PJ & Smiley released under the name Rum & Black. On the mostly instrumental LP Without Ice from ‘91, the duo’s love of Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakomoto underlines beat-less synth sketches like “In Memory Of” and “Black Revolutionaries,” while the fractured drum programming on “Insomnia” predicts the broken beat movement championed by the the likes of IG Culture and Bugz In The Attic almost a decade later. But while PJ and Smiley actively challenged dancefloors, they also had a knack for crafting a catchy tune.

In May 1992, Shut Up & Dance almost topped the UK pop chart with “Raving I’m Raving.” This ultimate rave anthem was adapted from Mark Cohn’s Grammy-nominated “Walking In Memphis,” and transposes Cohn’s quasi-religious experience on a visit to Memphis to the collective ecstasy of a dancefloor rushing to house pianos and frenetic beats. Presales predicted a number one, but copyright issues forced the label to pull it from the shelves, and it languished at the second slot on the charts for just one week.

It’s worth noting that only two weeks prior, another ragga-rave record had reached number two. “On A Ragga Tip” by SL2 covered similar ground to Shut Up & Dance’s brand of reggae-laced breakbeat, but also signified a rise in tempo, as hardcore began to dominate the rave scene. In a 2005 interview with DJ History, Smiley admitted, “We never really liked old skool ravey hardcore,” [sic] but what’s evident is the duo’s love for the next chapter in the story of UK rave: jungle. Their sub-label Ruf Quality hinted at an evolution in the Shut Up & Dance sound in ‘92, and by ‘94 they were fully fledged junglists with the release of tracks like “Hip Hip” and “Coca Cola.” That led to the creation of the imprint Red Light, through which they put out a handful of now sought-after jungle 12-inches, most of which you can hear on a new mix which comes free when you buy a Red Light t-shirt.

The Ragga Twins would themselves go on to become jungle legends, but not before a short stint at a major label for their 1995 album Rinsin’ Lyrics, a ragga-meets-jazzy-hip-hop affair produced by Us3 of Blue Note records. Two decades later they had an international smash when Skrillex sampled them on “Ragga Bomb,” and they found themselves blowing up Stateside once again last year thanks to a collaboration with James Blake. A brand new Ragga Twins album will be released soon on Nice Up!

Nicolette would go on to guest on Massive Attack’s Protection, fronting the lead single “Sly” before signing to Gilles Peterson’s label Talkin’ Loud in the mid-’90s. She subsequently followed Shut Up & Dance’s lead by setting up her own imprint, Early Recordings.

Since the advent of jungle 30 years ago, PJ & Smiley have plugged away in the studio, releasing hundreds of singles as well as the occasional album, continuing to push the envelope when it comes to basslines and breakbeats and spawning a number of new aliases as well as a UK garage label at the turn of the century called New Deal Recordings. “Out of all the scenes we’ve been in, the UK garage scene was one of the best,” PJ enthuses. “It was so healthy, and sold by the bucketloads.” Tracks like “True VIP” and “Hold Tight” were picked up for major label compilations, and proved that the duo were still a force to be reckoned with.

Today, PJ is still tuned in to music. He’s currently playing “a lot of grime and drum & bass MCs,” he says. “I try and listen to the underground stations. If something captures my ear, I’ll Shazam it.” When quizzed about the possibility of a new Shut Up & Dance album, PJ offers a very enthusiastic “Yeah!” As for dream collaborators, he’s still thinking outside the box: “Skin from [‘90s indie rock band] Skunk Anansie, I love her voice.” After all these years, that big Dutch Pot is still bubbling.