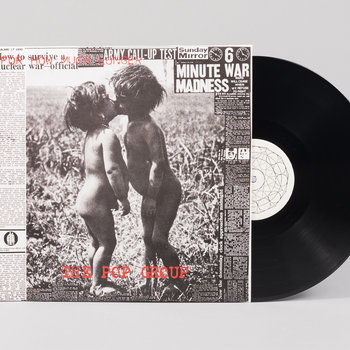

Mark Stewart has never been complacent. His pioneering post-punk outfit, The Pop Group, was born from a desire to disrupt the uniformity and hierarchy that punk in the U.K. had quickly formed in 1977. The Pop Group took their initial inspirations from a wide variety of influences, most notably black dance music (including the funk, soul, and disco popular in their hometown of Bristol, England at the time), the minimal compositions of Steve Reich, and avant-garde art/political movements like the Situationist International. The band broke up in 1981 (Stewart went on to a long and fruitful solo career with Adrian Sherwood’s On-U Sound) but found themselves celebrated in retrospect almost 30 years later. When the group re-formed with three of the five initial members on board in 2010 they found that they really enjoyed working with one another again and they’ve been active since.

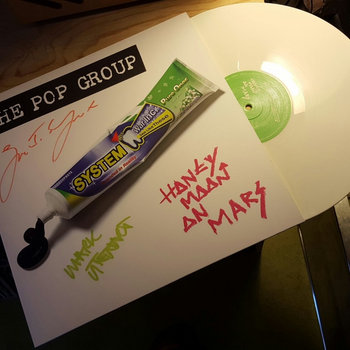

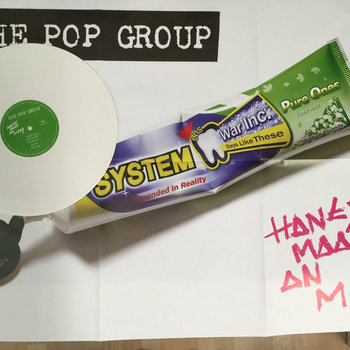

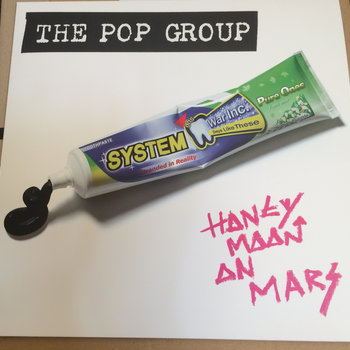

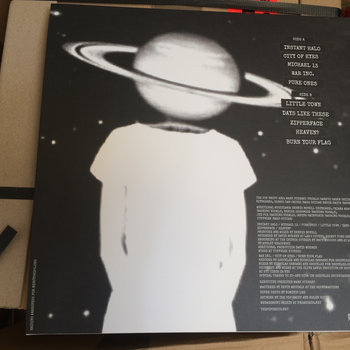

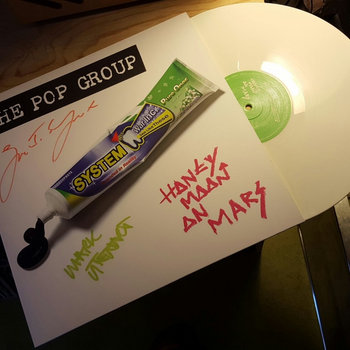

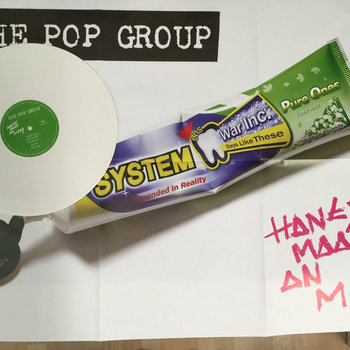

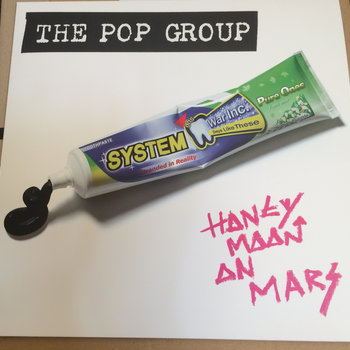

For their newest album, Honeymoon on Mars, The Pop Group worked with Public Enemy visionary Hank Shocklee to craft the latest version of their uncompromising vision, mixing dub rhythms, microhouse structures and beats, rattling and harsh experimental soundscapes, and Stewart’s spoken word. Their latest single from the album, “War Inc.,” is a benefit for Doctors Without Borders.

We spoke to Stewart about utopias and dystopias, sci-fi dreamers and mad scientists, turning the world upside down, and why Public Enemy was without a doubt a political punk band.

I’m curious what you think about the way the underground and the mainstream constantly work in dialogue with one another, and how that changes as technology progresses.

The way I see it, so much of this new technology is completely punk. Punk was a kind of startup culture, in a really weird way. I’m a real sort of tech-head anyway; my dad was a sort of mad scientist. I’m really interested in the way these things mutate, like cryptocurrencies and all of this weird shit that’s going on now. I was just reading something about hypersonic weapons and AI robot soldiers. But we have this saying—’the arrogance of power,’ which is the people who think they’re in control. But with punk, we had ‘the power of arrogance.’ We could just stand up and have a go, even though we didn’t know what the fuck we were doing.

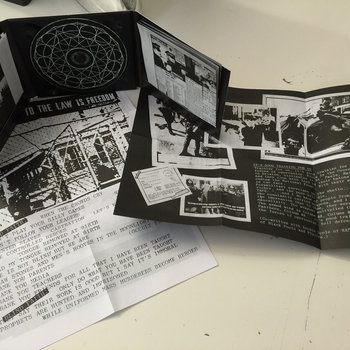

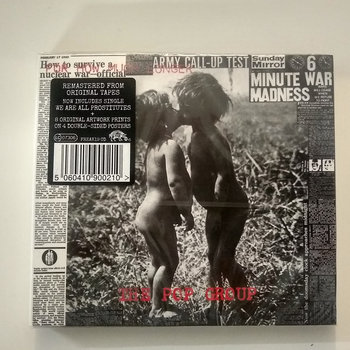

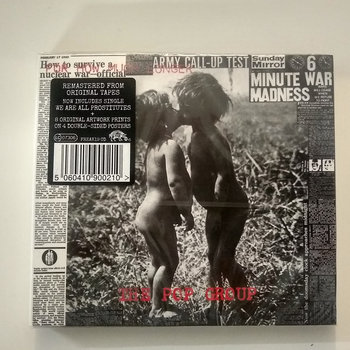

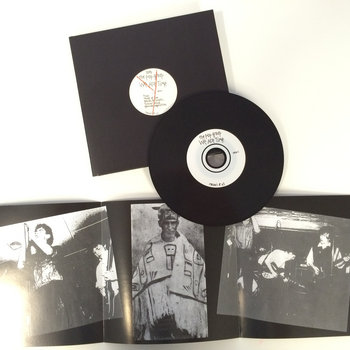

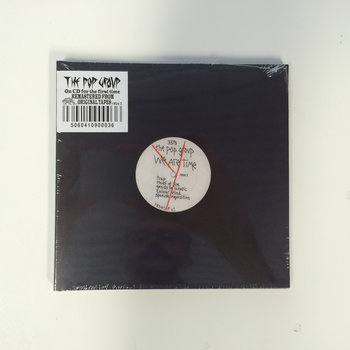

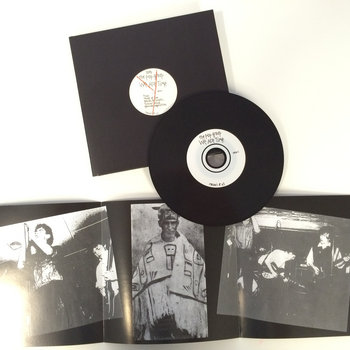

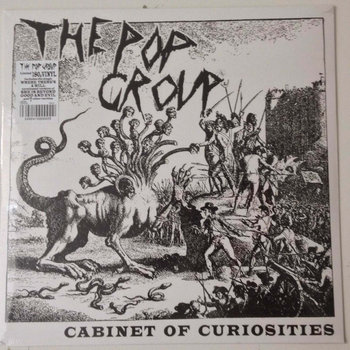

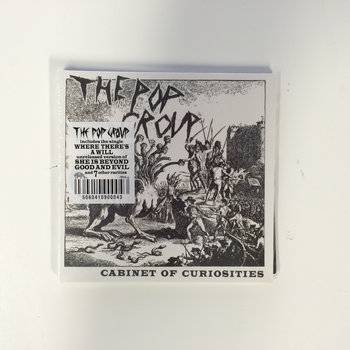

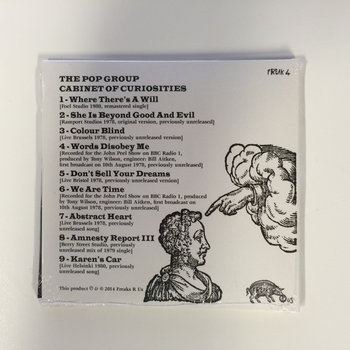

Compact Disc (CD), Vinyl LP

Right! You said that your dad was a mad scientist? What did he do?

He had a room next to my bedroom when I was small. He was always trying to paint, but he worked on the space program. And basically, he put himself through college, because the family only had enough money to put one kid through college, and they put their daughter through college. My dad had to start going to night school when he was working on the shop floor. He had to educate himself. He got to a point where he was really interested in lasers—this was back in the 1960s—and the craziest people would come to the house. He was basically a salaryman [once he started working on the space program], and there wasn’t a lot of money in his division. He wasn’t on a very high salary. But he was constantly pushing with loads of his weird mates—totally out-there people. The conversations they had in our dining room when I was a kid! I remember Arthur C. Clarke coming around. Basically, in the 1950s, in England, the dreamers and the idealists went to science. They were driven by comic books and Isaac Asimov novels and stuff. And it was those sort of things that helped them dream up where we are now with computers and… My dad constantly going on at the breakfast table, saying, ‘You have to be a computer operator’—we didn’t even know what computers were. When my brother said he wanted to be an artist, my dad said ‘You can paint the bloody bedroom.’

Yeah, exactly. We had the Internet super early at my house because my dad had to have it for work (he’s an electrical engineer), and my mom too—she was a librarian. I remember being very young and driving to the grocery store with my dad, and he said something like, ‘You know, at some point in your lifetime, everybody’s just going to have a phone number that follows you around for the rest of your life, and that’s just going to be your number.’ And I was like ‘Dad, no way. That’s ridiculous.’ And … now we have cell phone technology that allows us to do that.

Exactly! They were dreaming it! When cyberpunk kicked off, William Gibson and Pat Cadigan, who I really, really like—that’s half the concept of this [new] record, this Honeymoon on Mars thing. We have to now dream the future and seize the future, although though there’s really dark days. With what’s going on on television and news at the moment, you still need to be an idealist, and go out there and explore and be open and think about brand new ways for the future. The old guard is dying, and it’s all completely out of date. It’s not functioning, that system.

I wanted to talk to you about the idea of punk historiography—some people seem very determined to get stuck in punk nostalgia from 30 or 40 years ago. I wanted to ask you where you see punk going.

I think when [original punk and post-punk] bands started re-forming, there was this funny culture that developed here. There was this festival here called All Tomorrow’s Parties, that was curated by underground celebrities. People choose bands they want, old or new. The guy would approach bands to re-form—bands like Slint, who I don’t really know much about. It was a really weird culture. I was in Berlin, and I got a call from them saying that the guy from The Simpsons was curating one of their festivals and that he wanted me to re-form the Pop Group and Iggy to re-form the Stooges, and I just thought ‘This is the most crazy idea,’ because—for me, it’s like necrophilia. Not trying to be rude, I know some people enjoy necrophilia. But I’m always thinking about tomorrow. I never really think about the past. So I just thought it was a really stupid idea. I’d just done a big solo record, I’d collaborated with Richard Hell and Kenneth Anger—I was happy as Riley, you know what I mean? But I saw the way the scene was mutating—for me, The Pop Group, because of the way it’s respected and the effect it’s had on different generations, it’s become sort of a flag for freaks. And I just thought, ‘Why don’t I just approach making something new with these guys?’ We were still friends. Making something new, like a new commission… And I thought, ‘Right, we could approach it in that way, see what happens and make a new piece. It might be quite interesting.’

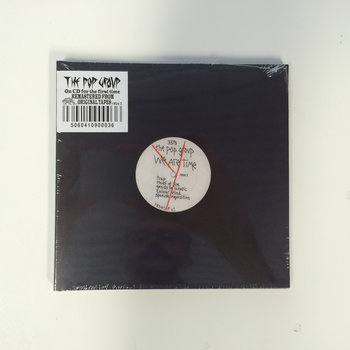

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

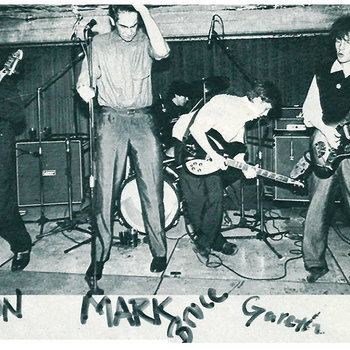

The Pop Group, for me, is a bit like a pirate radio station. It’s like a channel, a brand, that could start transmitting again. Because it stands for something which we all respect… our side of punk was the whole DIY thing and Rough Trade and independence. There was a whole kind of anti-style thing. We played in the back of the audience, or on the floor. It was really against the idea of the pop star, that anyone could jump up and have a go. It was a kind of enabling time. So it’s quite interesting to work under that kind of banner again. I think it’s cool. None of us really needed or wanted to do it, but something started happening which I wasn’t expecting, none of us was expecting. Even tomorrow, I just had a conversation with Gareth—we’re doing something tomorrow for a radio station here. Gareth has come up with something [for that] that I would never imagine doing. So it’s kind of like having three cars crashing to a head, these rehearsals. No matter how kind of smart I think I am, or how much I like being in control of my solo stuff, having renegade, lateral, feral people suddenly coming up with something you could never come up with [on your own] is destabilizing, and quite annoying half the time, but the next day you think, ‘What the fuck’s that?’ A new baby is born and you have to feed it.

That’s the best thing, though. When you come together with people to make something and they throw something into the mix you’d never expect.

Yeah. I’ve got this saying—I’m in this art group called The New Banalists. I’ve got this saying: ‘Taste is a form of censorship.’ When you think you know something… Sometimes I just pick something up in a junk shop I’d normally never think of buying, just to twist myself out of habit.

It’s really interesting, doing crashes with other people.

When you stop growing you die, right? I can’t imagine not being actively engaged with and interested in the world around me—if I thought I knew everything there’d be no way I could.

Be naive! Be childlike. And the funniest thing is, the world is—there’s two parallel universes. There are people who are depressed, living in this sort of grey world—what’s that film, Pleasantland?

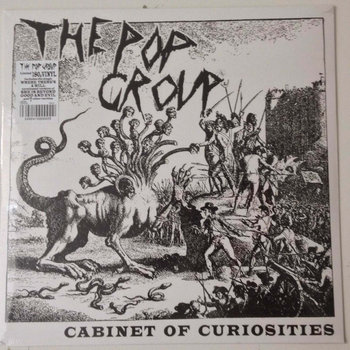

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Pleasantville. But if you just smile and look to what I call the side reel, it’s amazing—it’s glittering, it’s magical, there’s amazing shit going on. You just have to funnel it and not get caught in the lie [of no hope]. It’s a Society of the Spectacle situation. I’m reading this thing about lucid living right now. It’s crazy. You’ve only got one life. It’s really important at the moment that conscious people really dig in and push and have a go at doing something rather than just sitting back and moaning.

It’s like looking outside the prescribed uses for a consumer good.

Yes! That’s what the last record, Citizen Zombie, was about… it’s kind of like—when the astronauts would go on those space walks, and they had that umbilical cord connected to the space station. [When you look outside the prescribed consumer world], you’re suddenly floating in something you don’t understand. Everything you were taught is wrong. You realize the whole political system is an illusion, it’s a scam. It’s this whole sort of Matrix thing. And suddenly you feel like one of those space walkers, floating in this black universe. But then, you find some rainbow dust.

There’s the potential to go in so many different directions once you lose the map.

Exactly. I don’t like using the word ‘artist,’ but I think that’s the function of what we do. We’re like explorers. And if Baudelaire, back in the 1890s, or Rimbaud, or some weird Dada guy, hadn’t have gone after the craziest ideas and hadn’t been called a freak or a nutter—Antonin Artaud or whatever—I wouldn’t be who I am. So it’s important for generation after generation that people do these weird out-there experiments.

So what other themes and ideas are you working with on this record?

It’s the same kind of idealism [we’ve been talking about]. There’s something going on in the States at the moment, it comes out of the Occupy movement. It’s called ‘Occupy the Future.’ And for me, that kind of sums it up. Jaron Lanier wrote this book, Who Owns the Future? But for me, the concept is: we’ve got to dream the future, like my dad or your dad, like the sci-fi writers, like the cyberpunk guys in the ’80s. Whatever we’re thinking about and talking about and conjuring up now will grow and feed things for the future. No matter how dark the days now, in the darkness little shoots grow. And these new technologies can either be enslaving or they can be enabling. But you have to deal with the new as it’s happening. There’s this guy called Joseph Stiglitz who’s doing what they call the “new economics.” There’s no point in going on talking about the retro, or the past, why aren’t there blokes with beards in record shops any more? Fuck off!

As in, none of that matters now?

It didn’t matter then! I never liked those blokes with beards. They tried to out-weird you. Like Sudoku, some kind of mental puzzle. ‘Do you have any Albert Ayler?’ ‘No, we don’t.’ Then you go look for it and it’s right there in the racks. ‘This is an Albert Ayler record in the Sun Ra section!’ ‘Oh, I wouldn’t know, I listen to progressive, I’m not into jazz.’ They’d stroke their beards. ‘I’m much too open-minded for that.’

People don’t realize that in the 1970s, before punk rock happened, England was really like a Monty Python program. It was really a crazy place.

Expand on that, I’m curious as to what you mean.

In the 1950s and 1960s, it became a very staid class envy-driven… England was a very twisted place, I will tell you. They really wanted to keep people in their place. State-controlled media, state-controlled newspapers. And suddenly, when Jamie Reid, the Sex Pistols guy, put a pin through the Queen’s nose, you cannot believe how radical [that was]. Look at some of the early Sex Pistols interviews, just look at the TV presenters. It was like something from the 1920s or 1930s. The BBC was all bow ties. It was so staid. And speaking of the historiography of punk, it was a really radical moment for the whole society. These little tiny villages and towns, these people walking around with crazy t-shirts and mad hair. And it was a real upheaval. I think that has affected society across the world.

There are still definitely kids making really urgent and necessary punk around the world, like in Malaysia, or Mexico City.

You’re the first journalist to say that. People keep asking me, ‘Where’s political music at the moment?’ I say, one of my friends works with this organization called I.R., Indigenous Resistance. He works with loggers’ kids in Burma, kids in East Timor, who are using music like the troubadours did, as a way of communicating, like Woody Guthrie did. People are using hip-hop, too.

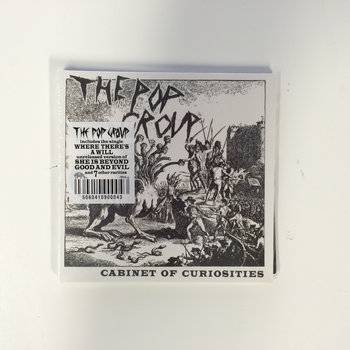

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

We did a piece on indigenous hip-hop throughout the Americas a few months ago, about people who are using hip-hop to tell their stories. A theme a lot of them came back to was oral tradition, and how huge that is in hip-hop culture, and how that’s helping them tell their stories.

In Bristol, what happened was that there was there was the punk thing—we picked up cheap guitars from Woolworths, we saw Paul from the Clash with stickers on his bass, and there was the thing of ‘just three chords.’ But then a few years later, loads of my black mates and slightly younger mates—I heard hip-hop really early on because we were in New York playing a lot in the no-wave times with Gang of Four and stuff. But when it hit the streets in Bristol, kids were getting strips of lino and watching breakdance songs and breakdancing, and the whole sort of punkiness of, ‘I’m just going to pick up a microphone and two little record decks.’ It was even punkier than punk. Anyone could do it. You could rap on the street. And it opened it up so Massive Attack, Tricky, all my mates in Bristol could have a go. I think hip-hop is great. That’s one of the reasons I was so pleased we got to work with Hank Shocklee, the Public Enemy guy, on this record. Because for me, when Public Enemy broke in England—the whole noise thing—it was pure political punk.

I’ve said this to so many people over the years, but I feel so lucky to have grown up in D.C.—

Go-go!

Right! Where go-go and punk were on the same bill a lot of the time.

Brilliant! I think the Junkyard Band were part of that? Wicked. I think [D.C.’s] a bit like Bristol, in that it’s not so segregated in parts of the city. Minor Threat and Fugazi are from D.C., aren’t they?

Right. Fugazi and Junkyard Band were on the same bill for a show… I think it was my sophomore year of high school? At a community center. Super close to my house. And kids from every neighborhood showed up. It was incredible. When Public Enemy came out, I was a skater kid, and it blew everyone away.

Yeah. When they did that collaboration with Anthrax, even—like Run DMC and Aerosmith—it was like ,’Who the hell would do that?’ Heavy metal kids and hip-hop kids didn’t get on. It was amazing. That was a real way to cross the racial divide. Brilliant juxtaposition.

—Jes Skolnik