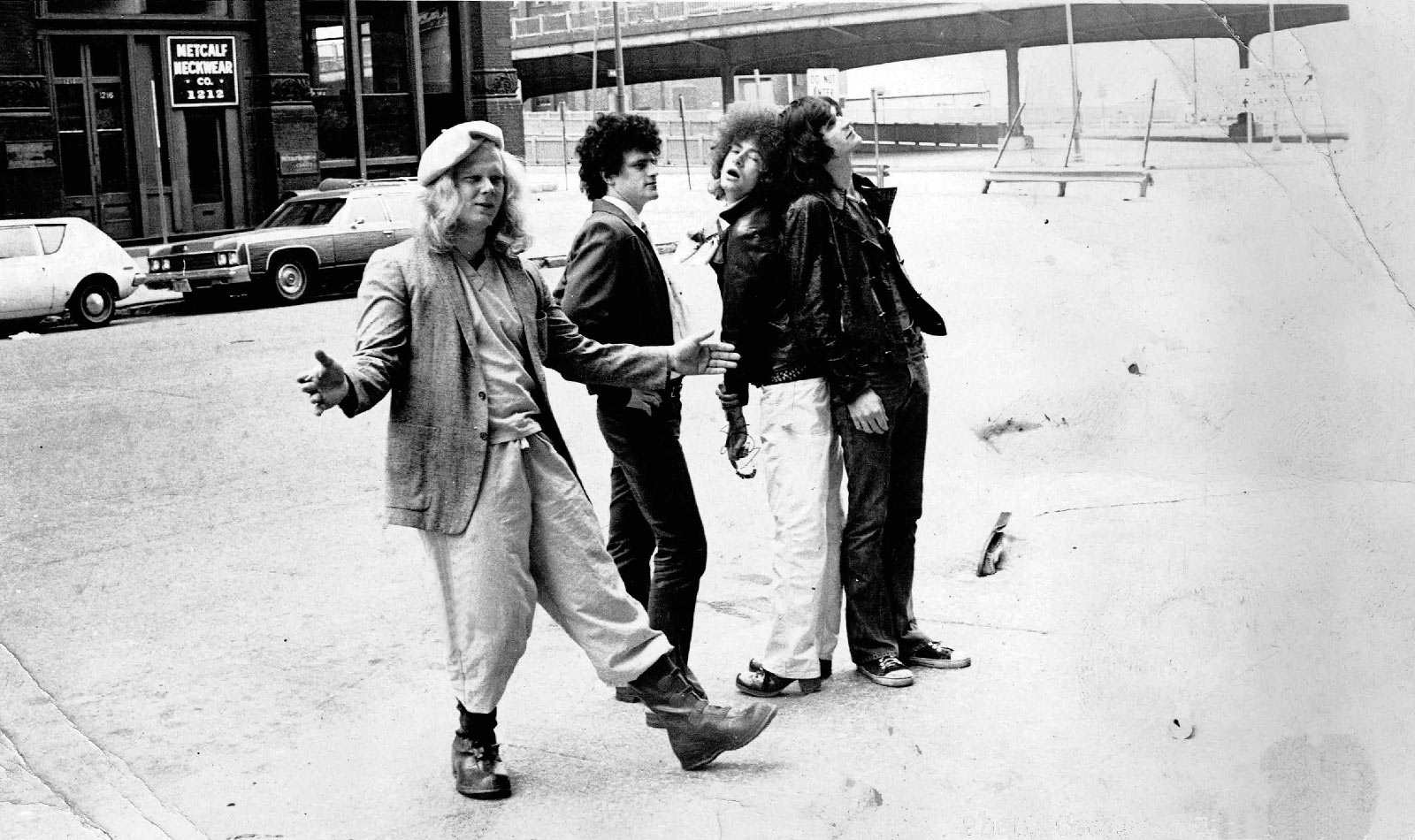

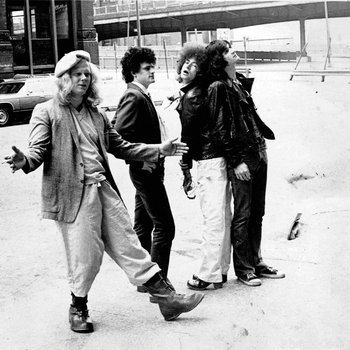

Photo by Michele Zalopany

Photo by Michele Zalopany

The truth about Cleveland’s Electric Eels, should such a thing exist, is as slippery and hard to grasp as their namesake. Their simple, saleable myth is compelling: a violent, antagonistic outfit who played five gigs in their lifetime and didn’t release a lick of music until they were dust, yet somehow achieved legendary status as punk and post-punk pioneers long before their popularization.

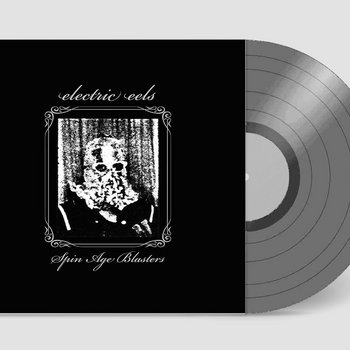

2 x Vinyl LP

Ornery, uncomfortable, and frequently off-color by modern standards, Electric Eels’ music was also undeniably, frighteningly alive: a mix of snot ball hectoring, splintered guitar fragments, and ragged, untamed melodies—all of which can be found on a new compilation, Spin Age Blasters, courtesy of Scat Records. Formed by high school friends with a penchant for Albert Ayler and Sun Ra, the band existed from 1972 to 1975 as a theoretical stake to the heart of a local music scene given over to limp top 40 cover bands. Guitarist John D. Morton has previously stated that the band was formed out of dismay at the bland act supporting Captain Beefheart And His Magic Band, but even this neat soundbite remains open to question: “That’s a very individual take,” says guitarist Brian McMahon.

“I had no feeling that that was an epiphany for me. Interestingly, they had a bit of trouble onstage with each other—I guess Beefheart also had that dynamic through the years.” Soft-spoken and understated to a fault, McMahon is alluding to a key part of the Eels’ mythos: the bouts of physical violence that would erupt onstage and off. “It was not fun in a physical way, just like a hangover’s not fun,” says McMahon of his time with the band. “It was fun conceptually, it was fun acting it out, but it was a problem. We’d take it out on each other, in our personal lives and our life as a band. There was a lot of drinking going on. I could hardly say the music was not enhanced by the life we led. It was maybe an actual working part of the composition—I think it was one of the ingredients that brought us together and sustained us.”

Like the humdrum household items that can, when combined, be fashioned into a bomb, the Electric Eels proved similarly combustible. Both within and without the chaos was another school friend, Paul Marotta (also of fellow Cleveland art-punk oddities Mirrors and The Styrenes), who served as guitarist when McMahon temporarily tapped out. He was also the band’s engineer and de facto archivist: it was Marotta who made the band’s first unsatisfactory recording when they’d briefly relocated to Columbus. “They were well known to me as lunatics,” says Marotta drily. “I mean, a neighbor came down to complain about the music and John pulled a knife on them, you know? The behavior was a little over the top, but it was definitely exciting music and I was only going to spend a day or two at most with them, so I could handle that.” But, almost before he knew it, McMahon had skipped out on the band and Marotta found himself a fully-fledged eel, moving to Columbus along with drummer Dan Foland. This iteration of the band mustered two gigs, the first of which ended with the arrests of Morton and frontman Dave “E” McManus. After returning to Cleveland, the band shared living and rehearsal space with Mirrors. They attempted further live actions, including the “Special Extermination Music Nights” with Mirrors and Rocket From The Tombs—one of which saw McManus wheeling out and “playing” a lawnmower. “That show was just a disaster,” says Marotta. “I find it appalling that anybody cares about it—there was nothing redeeming about it. Not a single thing. So I quit the band again and Brian came back.”

While the chaos, carnage and confusion of the band’s existence are writ large, this also belies a deadliness of intent and a near-monomaniacal seriousness. “The band practiced all the time,” says Marotta. “I think it was Dave E. or John who asked if I’d record them—they wanted to submit something to a radio station, thinking they were going to be put on the Live in Cleveland show. I made three recordings, and each song was probably played two or three times. Let’s say there’s five takes of a song—each take’s exactly the same length, to the second. It was just all junky equipment, a mishmash of stuff with a lot of mixers plugged into each other. The band played in a circle, which is the absolute worst possible way to record guitars because they just bleed into each other, but it just really fell into place.”

The diligence with which the band practiced was accompanied by certain delusions—if not of grandeur, then at least of simple popularity, with Morton mentioning being taken aback by the band’s lack of popularity when speaking to British newspaper The Guardian. But despite the energy, the melodies and the undeniably great songs, this was vitriolic and vengeful material—not the kind of music you can imagine suburban squares bopping their heads to over a convivial game of bridge. “I don’t know what made us persist,” admits McMahon. “I think if there was some kind of energy that held us together, it was negative energy. And it was violent. A couple of times in my book [Jaguar Ride: Memoir of an Electric Eel, released by HoZac Records] I make reference to the psychology of the band and the fact that we could have used some therapy. But at the time I didn’t think about that, I was always trying to just write a hit single.”

2 x Vinyl LP

If the crackling sense of discontent ensures the music retains its urgency and vitality after nearly 50 years, it has also sustained deeply-held grudges and animosities. “That’s a big part of why we haven’t had a record stay in print,” says Marotta. “Nobody can stand working with the band. I worked in the music business for 35 years, and if a band came to me and they were fighting they would not get past the front door.” This business knowledge, though, also meant Marotta was well placed to steward the band (minus Macmanus, now a born-again Christian who relinquished his rights to the band’s material) towards a contractual new-normal that ties them together, whether they care to acknowledge each others’ existence or not. “I learned how record companies could fuck over artists,” says Marotta, “and I believe in my heart of hearts that every single person should be paid for what they create.”

While there might not have been any hits, the band’s appeal has been enduring and their legend continues to grow—something the members find gratifying if slightly baffling. “I always thought we were an ephemeral band,” concludes McMahon. “I liked the fact that we got drunk and played and then went back to the bar. That you threw the guy with the chops out and got someone in with heart to have a better band. But I think there was something different to us, and maybe the fact that none of our subsequent bands really achieved anything shows that it was a one-time thing—because we could only stand each other and that atmosphere for a couple of years.”