It’s a Friday night in Bushwick, Brooklyn at the ramshackle, cozy DIY space Noise Workshop (formerly Secret Project Robot). Double bassist Damon Smith, a hardcore punk rock disciple turned free improvisational titan is fully in his element, helping unleash an impossible firestorm of loud noise. Other noise musicians have their “noise tables,” an arrangement of synths and other machinery they use to produce their crushing sound; Smith, on the other hand, towers over a sheet music stand stocked with a junkyard’s worth of miscellaneous contraptions—bows, drumsticks, clothespins, and chains—all ready to be rammed, prodded, poked, and spun into his bass strings.

“A lot of that stuff came from Barry Guy, the bass player, and Bertram Turetzky, who did a lot of prepared bass. It was just a way to get out of traditional playing and expand the palette of what you’re doing,” Smith says of his unconventional practices. Smith’s imposing and beefy techniques of attacking, scraping, and bowing the bass strings—and occasionally plucking out some swinging bebop-ish lines—with abandon has provided the serrated and rhythmic backbone and telepathic interplay for, and with, some of the world’s best improvisers.

Smith, who was a student of Lisle Ellis (who played in Cecil Taylor’s band), has been one of the driving forces behind the creative music scenes in both the Bay Area and in Houston—the former with experimental guitar pioneer Henry Kaiser, extreme-music drummer and Lydia Lunch/Retrovirus guitarist Weasel Walter, clarinetist Jacob Lindsay, and Brooklyn-via-Oakland guitarist Ava Mendoza, and the late altoist Marco Eneidi; the latter with guitarist Sandy Ewen and trombonist David Dove. Wherever the nomadic Smith has journeyed, he’s spearheaded an out-jazz community where the art of improvisation is its raison d’être. Sure, Smith’s long list of collaborators is star-studded (Brötzmann, Taylor, Sun Ra Arkestra leader Marshall Allen, to name a few) but Balance Point Acoustics—the record label he’s launched in 2001 at the suggestion of the late great German free jazz avant-garde-ist, Peter Kowald—has served as a document of his work and evident of the valuable alliances he’s shored up.

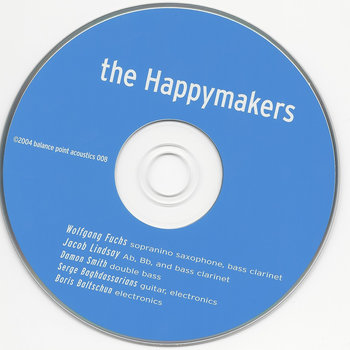

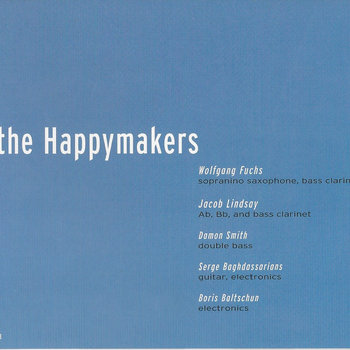

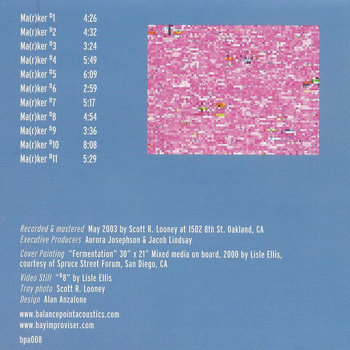

Compact Disc (CD)

It’s fitting that on this night, the hulking and well-traveled forty-something Smith—who has made indelible marks in the vibrant creative music scenes in Oakland beginning in the ’90s and into the ’00s, and more recently in Houston and currently in his new-ish digs in Quincy, Massachusetts—is sharing the stage with two of his kindred spirits: Kaiser and Walter. Both played crucial roles in Smith’s bridging the gap of his DIY punk roots with improvised music.

Smith discovered Kaiser early on, as a teenaged freestyle BMX bike-riding punk rocker schooled on a healthy dose of the seminal SST Records catalogue in the East Bay of San Francisco. “I got into fIREHOSE and the Minutemen. The Minutemen records were, of course, really important,” says Smith about his beginnings. “Then I just started collecting SST Records and that led me into experimental music before jazz, weirdly. Kaiser and Elliott Sharp and Saccharine Trust, which was on the edge of being free jazz and punk.”

Proudly wearing the Minutemen creed “punk is whatever we made it out to be” on his sleeve, Smith—like his hero Mike Watt—slung the electric bass in Gamala Taki, a rock-oriented group he shared with clarinetist Lindsay; they took their name from a rhythmic practice system trumpet icon Don Cherry devised. With his record shelves brimming with wax culled from his beloved SST label, over 30 fIREHOSE shows under his belt, and even having a hand in once helping Saccharine Trust reunite, Smith found himself at a crossroads. His growing passion for free improvisation was outweighing his fleeting interest in punk rock.

Soon after, he would trade his electric bass for double bass, and he did finally get to collaborate with Watt in a double bass quartet performing material from the 1984 Minutemen classic Double Nickels on the Dime, which was also his introduction to Peter Kowald. “I pretty much went all the way into playing double bass only after hearing Peter,” Smith explains. “I realized an important step at that moment was to cut ties with my youth culture—to not engage with it in relation to my work. I had to make a choice. I felt like once I heard, specifically the German free jazz, it didn’t have that spiritual dimension as much. It was sort of brutal—they’re upset about being born after the war, they are angry at the German establishment, angry at classical music and all that stuff.”

Sitting in the Noise Workshop garden before he hit the stage, Smith reflected with us on the treasure trove of improvised music that defines Balance Point Acoustics, picking and choosing essential records from its vast oeuvre, ones that have shaped him as an improvising heavyweight in the company of luminaries like Joe Morris, Peter Evans, Nate Wooley, Evan Parker, and the aforementioned Kaiser, Walter, and Ewen.

Compact Disc (CD)

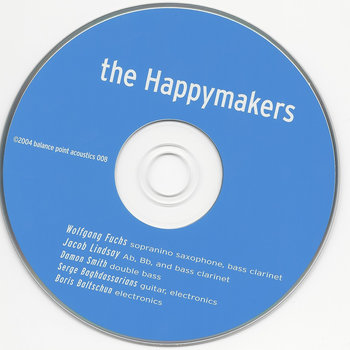

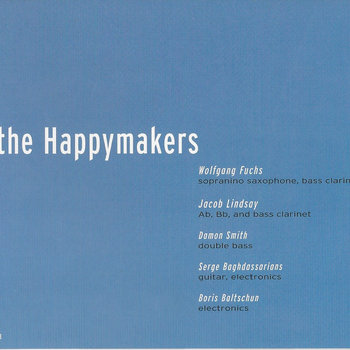

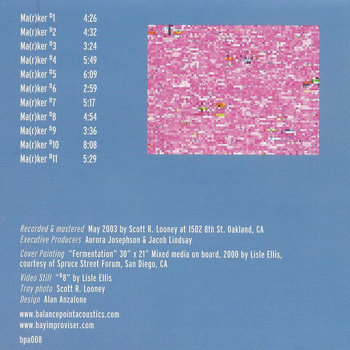

“We picked Wolfgang Fuchs because his approach was so refined,” says Smith of the self-titled set from The Happymakers, a drum-less quintet comprised of saxophonist/clarinetist Fuchs, Serge Baghdassarians on guitar and electronics, Boris Baltschun on electronics, and Lindsay. “As far as the music, this was the right choice to play with this guy because he kept his integrity the whole time until the end. He was a real grumpy old German man, but lovable. He had a really strong idea and was one of the first Germans to pull back from what they called ‘kaput-play,’ their hardcore free jazz thing. I think that album is really important because it’s 2003, but it’s at a really precarious time for the music when there was a couple of directions that everyone was pulling and then that album sort of sits on this juncture.”

Compact Disc (CD), Cassette

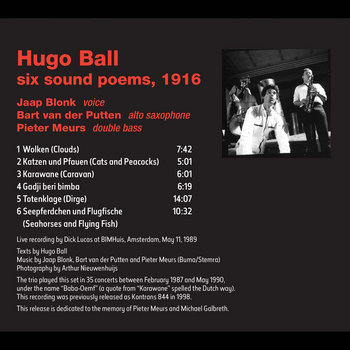

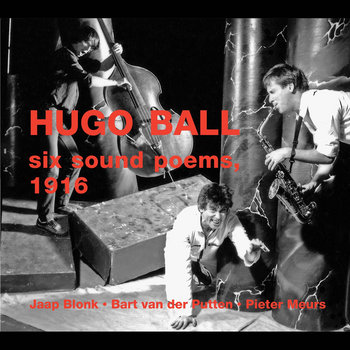

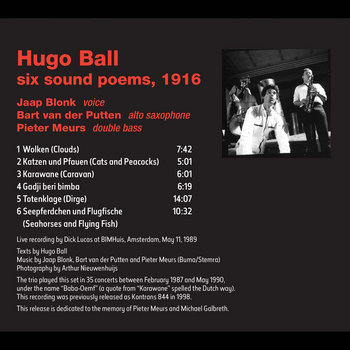

“The Hugo Ball is a really important album because it’s a work with Dutch sound poet Jaap Blonk,” recalls Smith of their bass/voice collaboration. “I met Jaap in 1998 in Sicily and he gave me a recording of Hugo Ball’s Six Sound Poems. Hugo Ball invented Dada at the Cabaret Voltaire in 1916. That release, which was recorded at a radio station, is special because it just had this great interface of visual art and art history and it provides music at the same time because I’m improvising along with Jaap. He used sound poetry as a way to ground his vocal improvising when he first discovered it. So he used that tradition of going back to 1916 and of those Hugo Ball poems. Then, Kurt Schwitters wrote ‘Ursonate.'”

“Weasel and I did this gig with Jim Sauter of Borbetomagus as a quartet with Sandy. Then the next day, we went to WKCR at Columbia and Anabel Anderson, the daughter of the great Ray Anderson, the trombone player, recorded that for broadcast. So it was broadcast and then Weasel put it out,” says Smith of his trio with Ewen and Walter. “That came out and it did really well. It was a minor hit, it sold a lot of copies, got around in a lot of places, got a lot of good reviews. Roscoe Mitchell was a fan of that trio and we ended up doing a gig with him, which was kind of amazing. I wouldn’t have asked him to play if that wasn’t the case. We kept hearing he would teach his improvisation class and he would use that record as a good example of improvised music. Then a few years later, Weasel came down and we did the second one, Live in Texas.”

Compact Disc (CD)

“The first one was all this electric upright that I had, and that thing stopped working, but it was cool when it worked. It had a great, bright sound to it. The next one, Live in Texas, was all double bass and Sandy and I were a lot more settled in together. It almost has more of a free jazz vibe to it and it’s almost a little more easygoing. It’s hot, it was in Texas, barbeques and beer so it was a little more laid back,” Smith says laughing about the trio’s second effort. He also stands in awe of Ewen’s miracle work on guitar. “It’s completely original and she never breaks abstraction. She never picks it up and plays it normal: always has it flat and never uses traditional technique.”

Compact Disc (CD)

“Alvin is also interested in free improvisation and knows the European drummers and that history but he’s really into swing,” says Smith about his longtime partnership and musical rapport with Alvin Fielder, drumming giant and founding member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. “Because I developed a really strong walking bass, we could really meet up there and be completely free to move to these other areas and mix it with free improvisation. That’s why we ended up needing to meet up with Joe McPhee. When Alvin and I play it’s almost not free jazz; it’s almost like a weird mix of free improvisation and jazz. There’s moments when we’re playing that we could be playing behind Lee Konitz or Sonny Rollins or what’s ‘real jazz.’”

“My first concert on the East Coast [after moving to Quincy] was the album with Joe McPhee and Alvin recorded at Roulette,” he says about Six Situations. “Alvin was in town to sue somebody [laughs] and we talked about playing together. This opportunity came up and I proposed the band, asking Joe if he was into playing and he said, ‘Yeah.’ I then proposed the group to Roulette and Jim Staley immediately wrote back. It was the easiest gig that I ever got in my life. It’s really recorded beautifully. My engineer, Ryan Edwards, got it really sounding great.”

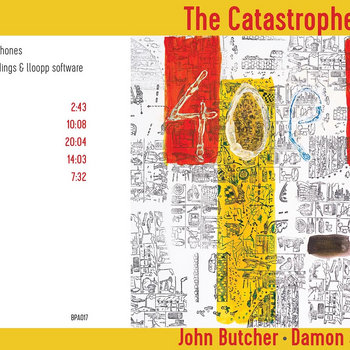

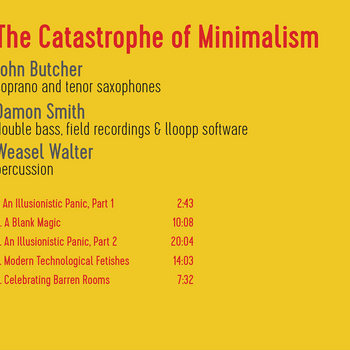

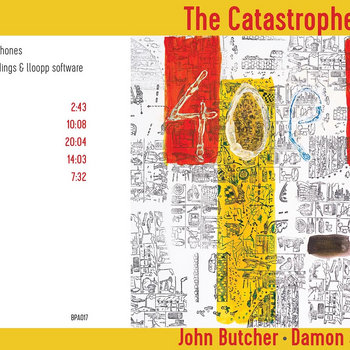

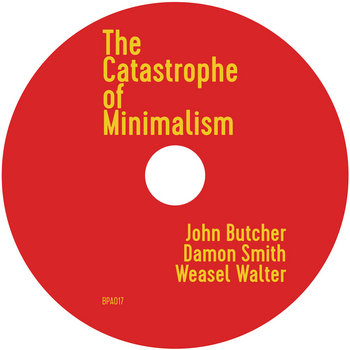

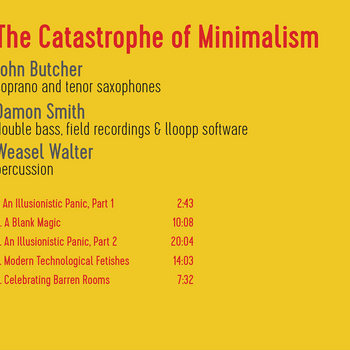

An ostensibly bionic-fingered powerhouse player who effortlessly hurdles from minimalist clang and clattering subtlety to maximal sonic assault, Smith’s deep-seated roots in improvised music and his undying mission to releasing records without compromise via Balance Point Acoustics is something to behold. He’s already prepping the label’s next release—a trio record with Walter and British saxophonist John Butcher.

“It’s important to try to get it out there, but nobody needs to receive it in a special way,” Smith says of improvised music. “There’s albums over time where your opinion changes about the music as you go through life. What’s interesting about it also, talking about what I’m doing with my Bandcamp page, is I’m trying to push all my work from the earliest release to the newest one. When you’re doing music like this, it’s all relevant. The work that I’ve done 20 years ago, it might be the right time for someone who’s working on a similar thing to hear now. Instead of copying [the music they hear], people can use that as a new starting point. People say, ‘I don’t want to listen to music because I don’t want to be influenced.’ But you should hear as much music as you can so you know what your context is, where you can offer something.”

—Brad Cohan