The southernmost island in the Mariana Archipelago has a few names: Guåhan, in the language of its native CHamoru inhabitants; Guam, as it’s widely known; and the “Tip of the Spear,” in the lingo of the U.S. military. That spear that stretches across over 800 foreign military bases across the globe—but with its location in the Pacific, Guåhan is bearing the brunt of the rising tensions between the U.S. and China.

“The most rampant militarism is happening in our islands because of the China-U.S. war politics right now,” says Shannon Sengebau McManus, one-half of indie pop duo Microchild along with her husband Jonathan Camacho Glaser. And with the island still recovering from the devastation of Typhoon Mawar, Guåhan’s colonial predicament has only become more apparent for some Guamanians; recovery has been slow, with many residents denied FEMA aid and some areas remaining without power for weeks.

But through it all, Guåhan’s music scene has been standing strong alongside organizations providing mutual aid like Para Todus Hit and Nihi. “There will always be that inherent Micronesian spirit that celebrates and smiles no matter what,” says McManus. In mid-July, organizers of the Beyond the Reef Music Festival held a fundraising event at Trifecta called Beyond the Relief, raising money for the Micronesia Climate Change Alliance. A wide cross-section of the scene’s talent, the lineup included ska band Fat Tofu and R&B artist Jonah Hånom.

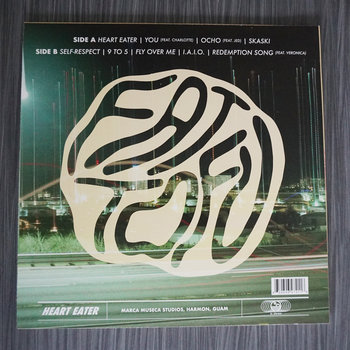

Vinyl LP

“[The venue] is known for just club music,” says RJ Aguon, drummer for Fat Tofu. “[But] I threw a somewhat of a hardcore show there once [at Trifecta], and the guy that runs the place had no idea. He never had a mosh pit at his club.” On a small island with much of its space reserved for tourists or the military, dedicated venues for underground music are hard to come across. In turn, event organizers have gotten creative with their choices. “We try to throw events in a bunch of different places,” says Aguon. “We’ve used the fine arts building at our local college. We’ve had access to museum theaters, warehouses, people’s homes, bars for sure.” Moistland, a house show series thrown by Freedom Fries guitarist Jordan Salinas, is remembered particularly fondly by members of the punk scene, and these days you’re likely to find the odd show at clothing shops like Good Lookin’ Out or Mom & Pop Store.

Aguon has his hands in many other projects around the island, including bands (Matala, KPV and the Homies), gig work in the tourist district, his solo project NOUGA JR., event organizing with 6AM Group, and producing live sessions with Binary Sunset. “I just wanna see our music scene grow, creating more spaces and programs to bring out the best from this place,” he says. “We’re actually trying to find a place right now so that […] we can kind of just host our own ideas without having to rely on a bar or renting a space from somebody in a place that doesn’t really wanna have us.”

Those spaces might be rare, but the few that do exist are cherished. McManus, who got her start in the island’s jazz scene, recalls Hagatña cafe The Piazza and House of Brutus as “formative spaces [that] felt like places where people could nerd out and get excited over something different happening in the village.” Learning the ropes while playing with CHamoru jazz pioneer Patrick Palomo and his group Tradewinds, she met her future husband and musical collaborator at a gig 11 years ago. And since 2018, their duo Microchild takes inspiration from McManus’s great-uncle Valentine Namio Sengebau, a Palauan poet who published an anthology of the same name.

“His poems heavily influenced my writing, and the way he seamlessly throws Palauan into a sea of English is how I try to approach incorporating the CHamoru language,” says McManus, who is of both Palauan and CHamoru descent. “The song ‘Navigator’ was written as a meditation on his poem ‘Torn Sail.’ The refrain at the end is a promise to our people that we haven’t forgotten their wisdom.”

McManus and Camacho are among a slew of artists in Guåhan and the diaspora working to revitalize the CHamoru language through music, including Micah Manaitai, Infinite Dakota, Andrew Gumataotao, and Jonah Hånom. But it’s not a new phenomenon; they’re carrying the torch of CHamoru pioneers like the Charfauros Brothers, Johnny Sablan, Clotilde Gould, Flora Baza, Terry Rojas, J.D. Crutch, Marianas Homegrown, Daniel De Leon Guerrero, and countless others from the ‘60s to the present, mixing their indigenous language with Western musical styles. And legacy in the scene is more than spiritual: “I actually play with the son of one of the band members in [Marianas Homegrown] and am good friends with another son of someone else who was also in that band,” says Aguon.

It’s often toward the goal of uplifting the CHamoru language and local spirit that musicians intersect across genres. Hardcore band SPEAR—who, according to an interview with How The Gods Chill, take their name from the island’s military nickname to “own the term as natives of Guåhan”—performed alongside Microchild, Jonah Hånom, and other artists at 2021’s Na’lå’la’: Songs of Freedom Vol. 5, an event held by Independent Guåhan. “There is a real fervor and excitement amongst our young people about learning their language and being proud of their heritage,” says McManus. “I’m not completely fluent; we definitely had to make the effort to learn. Jon invited me to a free CHamoru class that [scholar, curator, and organizer of Independent Guåhan] Michael Lujan Bevacqua had every Saturday at a local coffee shop, [and we’re] still in the process of learning, but it’s a journey we’re so thankful for.”

“Politically speaking, the CHamoru rights movement has grown and more artists are creating work that affirms our need for decolonization,” she adds. It’s a tough line to navigate. The colony—an unincorporated territory of the United States—has the highest military enlistment rate per capita of any U.S. territory, and about 13% of its population works for the military in some capacity. For three centuries before U.S. rule, Guåhan was a Spanish colony; during World War II, the Japanese also briefly held control of the island. Owing to that history, the island has a complicated relationship to the U.S. military, which at one point served as liberators from Japanese rule. “We all try as artists to have more of a nuanced view on things,” says Aguon. “The scene doesn’t run on a black and white perspective, the red or blue perspective.”

But in the U.S. bombing of the island, its largest villages of Sumai and Hagåtña were destroyed, and Guåhan was set to become a “permanent military fortress,” according to historian Michael Clement Jr. Through it all, the CHamoru language was suppressed—banned in schools and workplaces in 1922 by the U.S., children were told to speak English and their mother tongue was branded as “backwards.” “Our language was nearly wiped out by colonization, so every word and lyric is a testament to our survival,” says McManus.

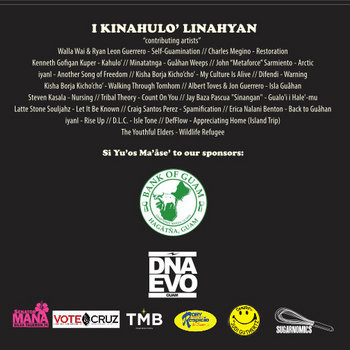

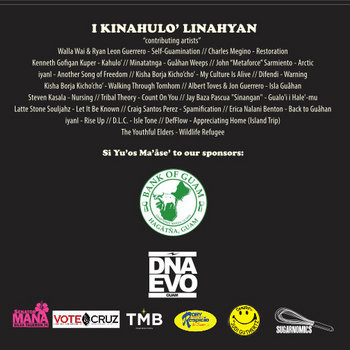

It was only until the mid-1960s when those language bans were lifted, but the damage was done: Michael Clement Jr. writes that the Charfauros Brothers were met with boos at their first performance in 1960, the audience “not in the mood to hear traditional songs” after a series of Elvis covers. While the Charfauros Brothers laid a certain foundation, it took Johnny Sablan’s debut album Dalai Nene—now a classic—to really kick off the wave of CHamoru-language popular music, riding the global spirit of decolonization in the ‘60s and ‘70s. The greater issues that these artists were facing have continued to this day—in 2012, punk-turned-political scientist Kenneth Gofigan Kuper helped put together a digital album of Guamanian poetry and music titled Kinahulo’ Linahyan [The Rising of the Masses] aiming to “fuel social consciousness and community participation.”

But no matter what one’s views are on Guåhan’s political status, the most important thing for artists on the island might be to be heard. “We are the ‘Tip of the Spear’ for the United States. That is our primary value,” wrote Michael Lujan Bevacqua on his blog in 2020. “But what is that value to us? To our cultures, our needs, our dreams? Is there more to life than that? Can’t Guam be more than that?” The musicians of all stripes on Guåhan show just how much the island has to offer; here’s some more artists from the scene.

Infinite Dakota

As Infinite Dakota, interdisciplinary artist-researcher Dakota Camacho raps in CHamoru and English, promoting their language from the Guamanian diaspora in Coast Salish territory (Seattle), where they’re now located. They take a freer, spoken word cadence on tracks like “Minalulok,” while on “Chålan Uenuku” they adopt a more metrical boom bap flow. Their path to hip-hop opened up initially from their exploration of the CHamoru musical tradition of kantan chamorita involving call-and-response and impromptu verse-making. In an interview with The World, they explain, “I was like, ‘Well, I can’t speak my language, but I can speak the language of rhyme. There’s a world in which I can exist.’”

NOUGA JR.

NOUGA JR. is RJ Aguon’s electronic side project, serving up wonky Brainfeeder-esque beats on an SP-404. Ever the community-minded artist, he brings his finger drumming to Drop Guam every Thursday for the 404 Thursdays series with Hardybum (Matala, Fat Tofu), Rdread (KPV & the Homies), and Zackawii (For Peace Band, The John Dank Show).

Local Deluxe

Pop-punk band Local Deluxe is a mainstay at the Every Show Ever series, often playing alongside the likes of Okas Point and SPEAR; guitarist Christian Sumalpong actually lends his talents to the latter band as well. They’re not only legendary on Guåhan, but have also toured Japan, sharing a bit of the island’s sound alongside Fat Tofu.

Surrender the Thief

Dr. Kenneth Gofigan Kuper features on this track by metalcore band Surrender the Thief, warming up his chops from his old metal band Hymn for the Tortured. While pop-punk and indie rock have become more popular in recent years, Surrender the Thief are carrying the torch for heavier sounds on the island along with SPEAR.

Okas Point

This EP from melodic punks Okas Point opens with an instantly-recognizable mid-’00s meme, which might be a clue to their irreverent attitude. Lo-fi and with more bite to their vocals than Local Deluxe, Okas Point scratch a different itch on the punk spectrum.

For Peace Band

It would be a mistake to exclude a reggae band from this list. “I feel like you see more reggae shows here than anything else. And they usually get the most sponsorships [as well],” says Aguon. One of Guåhan’s most prominent groups, For Peace Band’s message is straightforward, and it’s one that is becoming increasingly urgent.

Craig Santos Perez

A collection of spoken word poetry from poet and scholar Craig Santos Perez, Crosscurrent provides vignettes, musings, and manifestos on the CHamoru and greater Pacific Islander experience. “I wonder how many young Islanders have dived into the depths of a book only to find bleached coral and emptiness,” he recites on “The Pacific Written Tradition,” rebutting colonial notions of literacy and their repercussions today. “And always remember/ If you can write the ocean/ We will never be silenced.”