Got me feeling Presbyterian, but inside I’m still Liberian

—“No Way,” (2014)

Young Fathers are part of Scottish indie music’s history and present, (un)belonging within its all-encompassing white masculinities. Its three members include two Black African Scottish men and a white man. As stated in the notes section from the Bandcamp page of their first album, Dead: “This is known: Young Fathers are three young men from Edinburgh and Liberia and Nigeria, all at the same time.”

Scotland is well known for its musical output, from indie legends such as Cocteau Twins; The Blue Nile; Jesus and The Mary Chain; The Associates; Boards of Canada; and Orange Juice; to arena fillers like The Proclaimers, Calvin Harris, Simple Minds, Rod Stewart, and Biffy Clyro. Until recently, rap and hip-hop music in Scotland had been imported from elsewhere or dominated by white artists like Scatabrainz, Kryptik, and Steg G—a topic ripe for a different essay.

When Young Father’s 2011 EP Tape One surfaced, its depiction of navigating Scotland’s grey cities and long nights as a 20-something was familiar listening territory. The EP’s cover art features a photograph of a young smiling Black boy sitting on a chair. What appears to be candles topping a cake just make it into the shot. A celebration, maybe. Moving through the EP’s tracks, African ways only known to those who know were spoken, spat, and sung out in a Scottish accent. A mesmerizing and unfamiliar call.

Since the Scottish Independence referendum (to leave or remain part of the United Kingdom) in 2014 and Britain’s European Union (EU) referendum (to leave or remain part of the EU) in 2016, notions of nationhood, home, and belonging in Scotland have been shaken up.

Young Fathers’s 2014 Mercury Prize–winning debut Dead came out against a backdrop of frantic campaigning for the Scottish Independence referendum. Across the country, people organized, ignored, invented, and conspired. Amidst heated debates and discussions, alternative narratives were made visible; adorning hillsides, pavements, windows, and websites, creative expressions were produced by both supporters of “Yes” and “No, thanks.”

You were “Yes,” “No,” or “Undecided.” A “No” or “Undecided” could become a “Yes” and that’s all that mattered.

With Young Fathers, however, being Black African and Scottish/living in Scotland did matter.

You held me well/ I’ll hold you well/ You keep me warm/ All day/ All day.

—“Nest,” (2015)

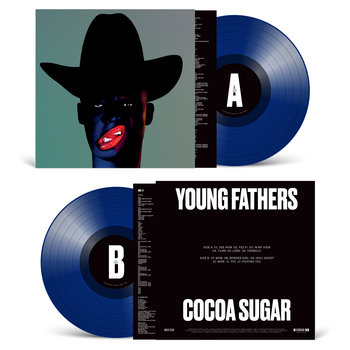

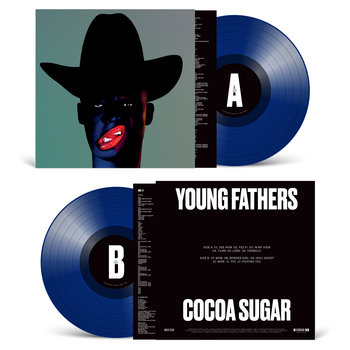

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD), Cassette

Young Father’s second album, White Men Are Black Men Too, followed in 2015. Released in the month prior to the death of Sheku Bayoh, whose life was lost after he was restrained by up to six police officers in Kirkcaldy, the album offers an eerily prophetic soundtrack. The Joy Division-esque “Shame” plays as a warning to institutions and individuals which discriminately kill and cause harm.

By the time 2016 rolled around, political/personal crises hung heavily. In June, Scotland would vote overwhelmingly to remain within the EU, serving as another marker of an identity distinctly different to the rest of the UK.

On the Monday following the Brexit Referendum in June of 2016, I learned my father had died. His sudden death at 51 was both expected and not. He’d struggled throughout his life with complex mental health issues and addictions, only finding solace in music. Whilst he was living, our relationship had been defined by his struggles, beautifully soundtracked by his vast musical knowledge. His love and unique way of understanding music was one of the very few things he could share joyfully and freely.

Clearing out his house, in and amongst things that somehow come to reflect a person’s life (and death), I found several mixtapes recorded onto CD, dedicated to me. At the time, I shoved them into a box, along with items which felt like an important part of his story to keep. Listening to them many years later, I couldn’t help but laugh when I heard:

I may not be around/ I may not be around/ No Jesus in my life/ No demons in my life.

These are the opening lyrics of “Rain or Shine” from White Men Are Black Men Too. I can’t recall us ever speaking about Young Fathers. When I occasionally listen to these mixtapes, they offer reminders of the ways you can learn to know and be with someone beyond life, unbound by circumstances and feelings which can make it difficult.

In October 2016, I returned to Nigeria, the country of my birth and my mother’s land, for the first time since leaving as an infant. I arrived during Felabration, the annual festival commemorating the life of Nigeria’s musical icon, Fela Anikulakpo Kuti. I’d come to know of Fela’s music from my father, and I felt them both with me, resurrected on the streets of Lagos.

A notebook entry from earlier that same year reads: In the space of 12 hours, I have met three incredible Black women in Scotland. Each representing parts of my self/identity I have struggled with. I felt a shift occurring within me on Friday. I believe this shift was an acceptance of self and with that, an acceptance of love. It was with one of these women that a friendship/sisterhood was formed. Through her gentle offerings, I grew and became grounded, learning theory to underpin my own experiences.

On returning to Scotland from Nigeria, I threw myself into building a Black (feminist) women-led collective, Yon Afro. The name was a reclaiming of hypervisibility and a nod to seeing Scottishness—”yon” means “that” or “those” in Scots. I’d imagined a scene from The Broons (a beloved Scottish comic strip), where a Black woman moves into the area and is described as “her with Yon Afro.”

As we discussed our understanding of seminal Black feminist texts, such as the Combahee River Collective Statement, we dreamed and imagined possibilities. We dreamed Black women-led collectives. We imagined these collectives as fiercely nourishing and self-sustaining. I hoped the collective wouldn’t succumb to inevitables.

After some discussions and care-full planning, we met—nervously. In those days we were self-conscious. What would a large group of Black women meeting look like? Food, feelings, and experiences began to be shared, and despite our differences, commonality could be found. Homes and hearts opened. We became the Yon Afro Collective. Small interventions into public life were made. Endless conversations about what Yon Afro was to become were held. People were excitedly invited to join. Tensions surfaced.

Perhaps those of us who gathered as Yon Afro sought healing, belonging, and a place for grief to be laid to rest. Perhaps we had all been called.

What a time to be alive (Wow)/ Imma put myself first (Wow)/ Everything’s so amazing/ I said wow.

—“Wow,” (2018)

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

By 2018, Yon Afro had both peaked and fallen apart. The bitter and the sweet of what we had shared was mirrored in the chaotic beauty of Young Fathers’s third album, Cocoa Sugar.

With confidence, contradiction and chaos, Young Fathers can do what Yon Afro couldn’t. They perform Black pain with passion and release, to be seen, heard, felt and consumed by all who come into contact. As Black women, ours is private, turned inwards and internalized.

Yon Afro’s last project to include every member in some form was a self-funded art exhibition held in a disused Victorian swimming pool titled (Re)imagining Self and raising consciousness of existence through alternative space as part of Glasgow International 2018. We joined art history, not as Black African women artists from elsewhere, but as Black African women artists living in Scotland.

(Re)imagining Self would be the last time we were all together, our internal and internalized disagreements about who we were as a collective—for the political or the personal—reached a climax. Being both was too big for our uneven Black consciousness.

Yon Afro and Young Fathers disrupted notions of Scottishness, particularly within the creative and cultural industries, and made visible the reality of being Black and/or of diasporic origin in a Scotland struggling with its own identity.

Cocoa Sugar encapsulates the feeling of being in a collective of Black women united in our experiences of whiteness and Blackness, otherness and outsiderness in Scotland, to those very things being what painfully separated us. Listening to the album’s fourth track, “Turn,” with its nod to Suicide’s Ghost Riders, connected me to pasts, presents, and futures we all share.

For the countless Black women unnamed in this essay, this is dedicated to us. I dream of a time when our stories of love, care, joy, anger can be released and realized with no expectation or analysis.

When we can be with the madness and sadness of living with enjoyment and without fear.

layla-roxanne hill is a freelance writer + organizer, living + healing in glasgow, scotland. she thinks, feels + acts upon many things, including the way our conditions move us to take action. she is also active in the trade union movement. layla-roxanne is co-author/dreamer of Black Oot Here: Black Lives in Scotland (Bloomsbury, 2022) + the freely available graphic novel + animation Black Oot Here: Dreams O Us. layla-roxanne can sometimes be found on the site formerly known as twitter @lrh151