It’s easy to think of “minimalism” as only the music of Philip Glass and Steve Reich, but the word also encompasses painting and sculpture and architecture—and beyond. Visual artists like Sol Lewitt and Donald Judd used simple materials and configurations; theater director Robert Wilson designed stagings with slow movements in austere settings, while musicians from Morton Feldman to Arvo Pärt worked with the bare minimum of plain phrases and rhythms. Paradoxically, minimalist works across all mediums are often maximal in physical size and scope, and duration. Obscuring definition and style, Judd, Reich, and others long objected to the term itself.

Minimalism was never an ideology, and it emerged almost spontaneously—one of those mysterious, complex cultural shifts—in the middle of the 20th century. It became, after the fact, an essential part of the history of classical music. But not only did the classical music world reject it for more than a decade, the style itself began both inside the classical tradition (Glass and Reich) and outside it (La Monte Young and Terry Riley). In one way or another, each of these four foundational composers were inspired by non-Western musical and philosophical ideas. Working from different personal aesthetics and musical backgrounds, they ended up sharing a fundamental concept of extended repetition while using it in vastly different styles.

And what styles! Minimalism has been one of the most powerful forces in all of music over the last 50 years. Glass has scored Koyanisqaatsi (1982), Candyman (1992), and other films and produced albums for the new-wave band Polyrock; the Orb sampled Reich’s Electric Counterpoint for “Little Fluffy Clouds”; Reich and Glass and Meredith Monk have been treated to remix albums; Terry Riley’s In C is played by every type of ensemble imaginable around the world; and on Metal Machine Music, Lou Reed acknowledged La Monte Young’s drone concepts. Not only are these composers still active, but the following post-minimalist generations of musicians continue to extend the style.

The best explanation of minimalism still belongs to Reich and his short essay Music as a Gradual Process, published in Source magazine. Reich wrote that the process itself determined note-to-note events, which in turn created structure; that he wanted to “hear the process happening” in music, and that the experience should be like “placing your feet in the sand by the ocean’s edge and watching, feeling, and listening to the waves gradually bury them.” The waves can be strong or gentle, they can come in rapid sequence or at a leisurely pace, but the idea of process is the same each time with each piece of music. And process is the thing; minimalist music (before Glass and Reich moved toward opera and text pieces) isn’t about anything and has no specific goal other than to start and stop and fill the space in between with experiences.

Here is a selection of some masterpieces of minimalism—some well-known, some obscure—available on Bandcamp.

Sō Percussion

Steve Reich: Drumming

Compact Disc (CD)

The process that Steve Reich used in the first major stage of his career was a technique he called “phasing”: taking two different patterns of music and moving them in and out of phase with each other. This culminated in what is arguably still his magnum opus, Drumming, a 75-80 minute work for percussion, singers/whistlers, and piccolo. Starting with the simplest possible beat, the players add instruments and rhythms, one idea surpassing another, like the waves in Reich’s metaphorical ocean. The initial starkness grows to be sonically lush and shining. This is process-as-life: plant the seeds, see the weather change, bask in the abundance.

Philip Glass

Music in Twelve Parts

Like Reich, Philip Glass’s definitive demonstration of his style and process came relatively early in his career, well before his fame. Music in Twelve Parts is one of the most maximal minimalist works—a full performance can take more than four hours—and came from a time when, like Reich, Glass had only his hand-picked ensemble to work with. With his mind on the legacies of composers like Mozart and Bruckner, this piece is a mesmerizing exploration of slow transformation using the traditional tools of counterpoint and harmony. Some parts are slow; some are frenetic; all have that special Glass sound that mixes organ, reeds, flutes, and voice and compresses every part into a Sol Lewitt-like surface.

Bang on a Can

In C

Compact Disc (CD)

Reich and Glass were never far from the classical tradition, while Terry Riley and La Monte Young were very much outsiders. In C is not just minimalist in style but avant-garde in how it’s organized. Any number of musicians can play it, and the instruments don’t matter; it has been played by orchestras, rock groups, artist collective Brooklyn Raga Massive, and on modular synthesizers. Based around a repeated C note, each musician has the same set of 53 short phrases that they play any number of times, though in a prescribed order (they can choose to skip any). It premiered at the important San Francisco Tape Music Center, played by an ensemble that included Reich and Jon Gibson, a long-time member of Glass’ ensemble. It was also recorded and released on Columbia Records in 1968 and was a popular success, making it not just an important work but an essential artifact of minimalism in popular culture.

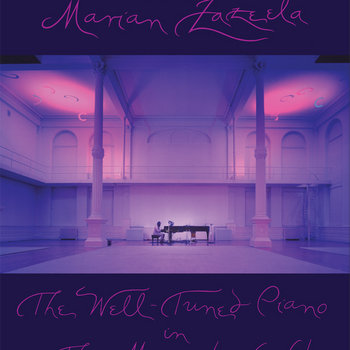

La Monte Young

The Well-Tuned Piano in the Magenta Lights “87 V 10 6:43:00 PM — 87 V 11 1:07:45 AM NYC”

DVD

Young worked from a very different idea of minimalism and process music, but one still connected to the overall movement in the arts. Where Reich, Glass, and Riley often use a rapid pulse and lots of activity, Young slows things down and opens up space for improvisation. The music is, in important ways, a path through which the performer and listener find some kind of enlightenment or touch a mystical experience. Balancing repeated units and freedom, this is again maximalist music. A performance can last up to six hours, with artist Marian Zazeela enhancing the event with her work The Magenta Lights. A very special and essential feature is that the piano is tuned to a variation on just intonation, based on the natural overtone series (Young has also adjusted the tuning through the years), giving the piano a sensual glow that helps separate the listener from the everyday world.

Nicolas Horvath

Tom Johnson: An Hour for Piano

Tom Johnson is a composer who also spent a dozen years as a music critic for The Village Voice, where he not only heard minimalist music as it was beginning but was one of the first to apply the word “minimalism” to what he was encountering—he also gladly used it to describe his own work. He bases his own process in rigorous logic, like in his The Chord Catalogue, which literally catalogs possible chord configurations on the piano, and has collaborated with several mathematicians. An Hour For Piano is just that—an hour of music on the piano. The repeated, simple melodies and left-hand counterpoint move in and out of minor and major keys—lovely, mesmerizing, and satisfying—and Johnson’s own liner note to the listener is a prose version of his music, circling back on itself, returning the same idea in a slightly varied context, lulling and charming the mind.

R. Andrew Lee

Dennis Johnson: November

Few ideas come out of nowhere. La Monte Young went to UCLA, where he was friends with Dennis Johnson, who wrote November, a piece that was Young’s acknowledged inspiration for The Well-Tuned Piano. The piece was unknown for decades; Johnson made a cassette recording in 1962 and then abandoned music and became a mathematician. Composer and musicologist (and also a one-time Village Voice critic) Kyle Gann used that cassette and six pages of the score to create a full realization, first recorded here by R. Andrew Lee. November has a similarly measured pace, sense of beauty, and duration to The Well-Tuned Piano, but is pure process music; all about how one simple idea transforms slowly through time into another and then builds. It has some of the sonic qualities of Satie, though a very different expressive quality and a full listen can be emotionally wrenching and cleansing.

Wild Up

“Stay On It”

Compact Disc (CD)

Julius Eastman is another musician whose work was essentially lost for decades. He was an important figure in the new music scene in New York as a composer, performer, and conductor—a living bridge between the high modernism of classical music, the revolutionaries of minimalism, and the downtown scene that was bringing together pop, rock, jazz, funk, and punk, often using minimalism as the common thread. He never had enough professional opportunities and suffered from what seemed to be, at the very least, severe depression compounded by drug use. He was evicted from his apartment and lived in Tompkins Square Park for a time before dying at the age of 49, alone, in a hospital in Buffalo. What he left behind was music that was often political but always full of explosive energy, and like his peers (especially Riley), used small musical ideas that the musicians pursued through to the end. This performance of the exuberant “Stay On It” has all the joy contained in Eastman’s work, tinged with a deeply poignant conclusion.

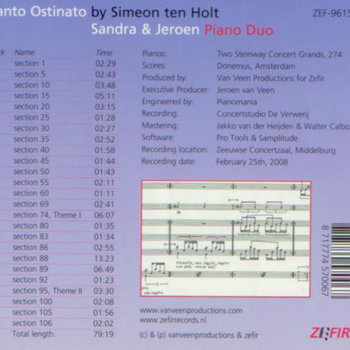

Piano Duo Jeroen en Sandra van Veen

Canto Ostinato

Compact Disc (CD)

Minimalism began in America but became an international style that was adapted and advanced by musicians like Michael Nyman and Louis Andriessen. In 1976, five years after Reich finished Drumming, Simeon ten Holt completed Canto Ostinato, one of the greatest minimalist compositions. It can be played by any number of instruments, as long as they can play chords (it’s usually played on keyboard instruments or tuned percussion). Like several other works already mentioned, it uses a large number of small units of music that the players can repeat any number of times (there are also several specific bridges used for transitions). At a steady tempo, a performance can last from an hour or so up to, conceivably, a full day. These theoretical details are the least of it; this is an astonishingly beautiful and lyrical piece of music, with an irresistible flow and shifting tonal harmonies that resolve into great vistas, like gliding through endless fields of sunflowers.

Laurie Anderson

“O Superman”

Vinyl LP

Laurie Anderson should never have been famous. An art world figure and experimental musician, her minimalist and irreverent “O Superman” somehow found its way onto repeated airplay on BBC radio—an unlikely outcome for a piece written off the back of an aria from a 19th-century opera. Yet the charm and luminosity of the music are there for everyone, and it shows how minimalism pares down music to the basics of a beat—rhythm, repetition, and changes through time—then builds them back up. Those elements appeal across the globe—no wonder then that minimalism spans eras and genres.

Elodie Lauten

Variations on the Orange Cycle

If minimalism has a slightly hazy definition, so does post-minimalism. Other than coming after minimalism, what is it? “O Superman” is one marker, with minimalist repetition and process put into a different context—a song, say, or an improvisation, one section of a larger piece. Another fair way to look at post-minimalism is the second generation of minimalist composers learning from the previous one and adding their own personal touches. Both are ways to listen to another sadly obscure composer who died too early. Elodie Lauten made important works for the stage, like The Death of Don Juan, and also the keyboard, where her music has a touch of both Riley and Young in its mix of repeated ideas and improvisation. Variations on the Orange Cycle began as an improvisation, recorded and transcribed for others to play. It’s meditative, bluesy, and reins in free passages with the insistent call of a single, repeated note.

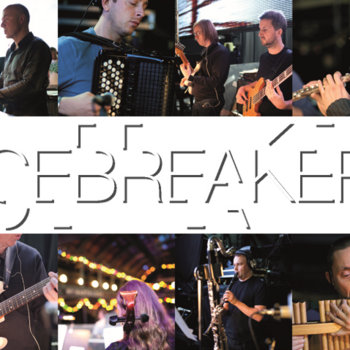

Icebreaker

“Yo Shakespeare”

Compact Disc (CD)

The standard-bearers of post-minimalism are Bang on a Can composers Michael Gordon, David Lang, and Julia Wolfe. Each has produced real masterpieces of the era, and “Yo Shakespeare” is one of the most important, with shifting slabs of complex rhythms that, if they weren’t from a “composer,” would be called rock music. The structures are mind-blowing and the attitude is ass-kicking, contemporary classical music that gives away nothing in terms of complexity but is for everyone. This is a virtuosic performance from Icebreaker, part of an album that is an absolute classic of 20th-century music and that includes pieces from Andriessen, Gavin Bryars, and Lang’s haunting Slow Movement.

Galen Brown

”God Is A Killer”

Galen Brown should be better known. He’s a thoughtful composer who has written an important paper on minimalist and post-minimalist music, and he uses the gripping and propulsive feel of minimalism to portray open-eyed views of fraught situations in the world, like in the existential drama of And Carthage Must Be Destroyed. He also is adept with music production technology and uses it the same way that rock and pop producers do. Nowhere is this better heard than this stunning, chilling, moving piece for piano with a taped, fiery Christian sermon that is synched and Auto-Tuned to the rhythms and harmonies of the score. There are very few things that can forcefully express both conflicting and ambiguous emotions like music, and there are few pieces of music that are as powerfully conflicting and hypnotically ambiguous, and complex as “God Is A Killer.”