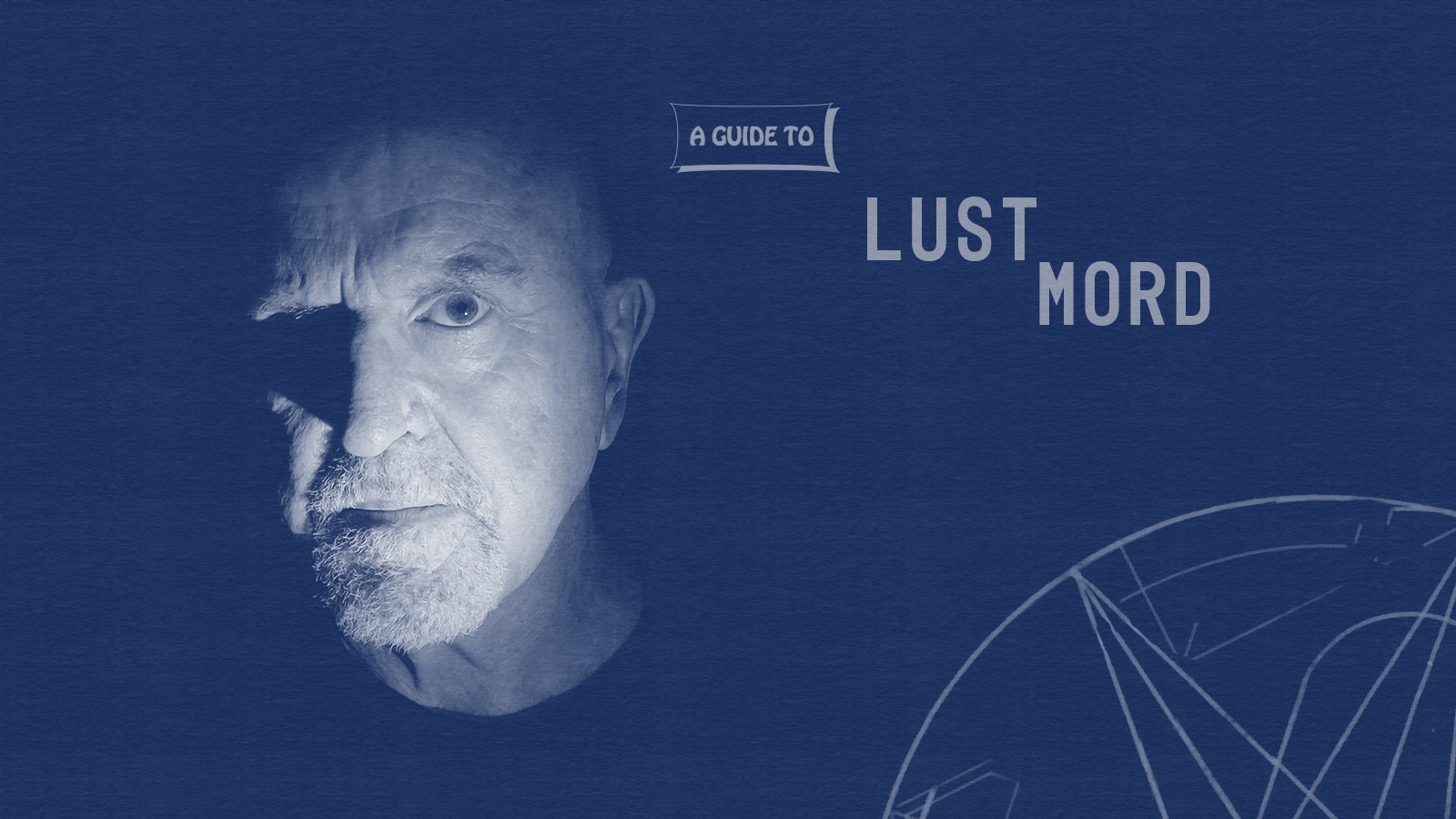

Welsh-born, California-based artist Brian Williams has been recording sprawling, cosmic electronic music as Lustmord since the early ’80s. As a reluctant pioneer of the dark ambient genre who regards his music as neither dark nor ambient, he’s often been a square peg in the scenes he’s been thrust into. “I never felt like a part of anything, to be honest with you,” Williams says.

“It’s interesting to me that people perceive a lot of what I do as dark, because it’s not,” he continues. “It’s very primal. It’s slow, it’s big, and my music takes you somewhere. It’s not ambient, it’s fucking present. It’s physical. And that’s what music is supposed to be. It’s not supposed to be ambient. It should take you to a very deep place.

“Interestingly, a lot of people go to a very dark place,” he continues. “They go to the cosmos or whatever, and it’s dark and scary. I don’t think it’s dark and scary at all. I think it’s fascinating. In an ideal world, people would call my music fascinating, but they call it dark, so what can I do? [laughs] I tried.”

Williams’s process is as singular as his music. He claims to have no musical ability. He’s not proficient on any instrument and he can’t read music. He works instead from a vast library of sounds he’s amassed over the years, some drawn from library music, others collected via field recording, still others acquired from unlikely sources, like the NASA Jet Propulsion Lab or the Manhattan Project archives at Los Alamos. Williams then uses digital software to manipulate those sounds into the spacious, post-industrial drones that make up Lustmord’s records and live performances. The point, for Williams, is the mood, not the gear. To that end, there haven’t been live synths on a Lustmord solo album in years.

Lustmord has a vast discography, and with most albums running well in excess of an hour, there’s an intimidating amount of music for newcomers to take on. In a long and wide-ranging conversation, Williams walked us through some of the highlights from his catalog, including his staggering new opus, Much Unseen Is Also Here. While these recordings span a huge range, both conceptually and sonically, they’re all animated by the same impulse: “The reason I started doing this Lustmord thing was I wasn’t hearing the music I wanted to hear,” Williams says. “So I had to do it myself.”

Paradise Disowned

The first Lustmord album came out in 1981, but it wasn’t until 1986’s Paradise Disowned that Williams started to figure out his signature sound. The album still had a handful of beat-centered tracks, indicative of his interest in Chicago house music, hip-hop, and dub reggae. But the ominous drones that would soon come to dominate Lustmord’s records started poking out as well. “On the Paradise Disowned album, I was trying different things and having fun,” Williams says. “I knew I wasn’t going to go any further with those beat things, but I was getting it out of my system, more than anything, to have some fun with and move on. The [non-beat-based tracks] were me starting to work on getting that sound I was looking for.”

Heresy

Between Paradise Disowned and 1990’s Heresy, Williams got an Atari computer. That may have been the single most transformative moment of his career. Instead of battling with modular synths, which he was never comfortable with, Williams could now sit in front of the computer screen and manipulate samples with a mouse. “For me, that was, ‘Ah, I don’t play any instruments, I can’t read music, but this I understand,’” he recalls. “When I was looking at the screen and seeing a sequencer, it was suddenly, ‘I can do it now.’”

Today, Heresy is considered a foundational classic of dark ambient. So many of the themes that Williams still explores to this day seem to arrive on the album fully formed. There’s the subversion of religious iconography implied in the title of the album and made explicit in the distorted spoken word bit from Milton’s Paradise Lost that Williams brings into the final movement. There’s also an ineffable sense of being taken on a physical trip through sound, something Williams has sought to do with every Lustmord album since. “My albums, in many ways, are journeys through this vast, empty space,” he says. “Starting with Heresy, I found myself on this journey into the universe, and I’m still on that journey, basically.”

The Place Where the Black Stars Hang

If the Atari home computer was the most important technological marvel for Lustmord’s music, the compact disc wasn’t far behind. Sonically, 1994’s The Place Where the Black Stars Hang was an expansion on the themes established by Heresy and recapitulated on its follow-up, The Monstrous Soul. But it was also the first Lustmord album where Williams pushed hard on the capabilities of the CD format.

“You’re really limited by the length of the vinyl side as far as how long a track can be, and I always do tracks by feel,” he says. “If they feel like they should be 50 minutes, they’re 50 minutes. As I’m working on it, the track and the mood I’m creating tell me where it needs to go and when it needs to stop. With CDs, you can go to 75, close to 80 minutes. And Black Stars was an opportunity to do something I wanted to do in the past, which was really long tracks that really pull you in.”

Pigs of the Roman Empire (with Melvins)

Collaborative work has been a constant in Lustmord’s career, and no collaboration in his catalog is more radical than Pigs of the Roman Empire. By teaming with the sludgy noise-rock band Melvins, Williams introduced live drums and guitars—and semi-traditional song structures—into his music for the first time. Pigs is full of boisterous metal parts and noisy drone sections, but don’t be so sure you know who’s responsible for each. “What was really fun about it was we deliberately did it the other way around,” Williams says. “The things on the album that people will think are Melvins are actually me, and the things people will think are me were actually them. Because we didn’t actually say who did what, it just says it was a collaboration.”

[O T H E R]

Live guitars made their return to Lustmord’s palette on [O T H E R], which features hypnotic, drone-y contributions from Melvins’s Buzz Osborne, Tool’s Adam Jones, and Isis’s Aaron Turner. These guitars are incorporated in a more classically Lustmordian way than on Pigs of the Roman Empire, but they retain their essential qualities. [O T H E R] doesn’t sound much like Tool, in other words, but Jones is allowed to sound like Jones. “The idea of actually using guitar to sound like another element didn’t seem to make much sense to me in the moment because all those other sounds I can do,” Williams says. “If I’m going to get a guitar to do those kinds of things, well, there’s no point in having a guitar. I could just do it myself. It was trying to get something in between.”

The Word as Power

Some Lustmord projects have long prehistories. The idea for 2013’s The Word as Power predated Heresy, but back in the ’80s, Williams didn’t know any singers who could pull off its demanding, vocal-centric compositions. (“I knew people that sang, but I wanted voices that worked in the way the sounds I create work,” he says.) He met Aina Olsen, the singer for four of The Word as Power’s seven songs, when she reached out via MySpace asking to photograph him. It turned out that she had been a pop singer in her native Norway decades earlier—ironically, around the same time, Williams was first thinking about making a vocal album. “I heard her sing, and the stuff she played me was nothing like what she did on The Word as Power,” Williams says. “But I knew, ‘Okay, this is a person who, not only can she sing in the way that I need for the album, she knows exactly the kind of feeling it needs.’ So this idea, which must have been about a 30-year-old idea, I could actually do it.”

Joining Olsen on The Word as Power are Tool’s Maynard James Keenan, who sounds downright Gregorian on the pulsing “Abaddon,” as well as former Swans vocalist Jarboe and the Tuvan throat singer Soriah. Their voices are absorbed intuitively into Lustmord’s soundscapes, adding a texture as natural as his foreboding electronics and warped samples. As an illumination of Williams’s collaborative spirit, there’s not a better specimen in the Lustmord discography. “I’ve always wanted to do that album, and I finally got to do it because I found the voices,” he says.

Dark Matter

Lustmord’s music often evokes the vast expanse of space, but with Dark Matter, Williams made the association literal. “I wanted to make this album using only sounds from space,” he says. “Well, how do you get sounds from space?” His wife encouraged him to contact the NASA Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena. Apparently, no one else had asked: “They took my address, and about a week later, this box, like a shoebox, arrived, and there were all these tapes in it. And they were the original tapes! They weren’t copies, they sent me the tapes.”

Combing through the tapes for sounds with a sufficiently musical quality was painstaking work. “A lot of it was just noise,” Williams says. But after 20 years of development, he had enough for an album. Much of Lustmord’s work is fixated on our cosmic insignificance as a species. No album makes that point more convincingly than Dark Matter.

First Reformed OST

Paul Schrader’s First Reformed (2017) is one of the most striking American films of the 21st century. It’s a stark, haunting piece of eco-agitprop, concerning the radicalization of a dying pastor (played by Ethan Hawke) who contemplates taking extreme measures to make the church reckon with its complicity in environmental destruction. As Hawke’s character journeys into a heart of darkness, Lustmord’s menacing drones guide the way. A long-standing and important sideline to the main Lustmord catalog has been Williams’s work for film, TV, and video games. Most of that music and sound design never makes it into the world in album form, but we’re lucky that First Reformed is an exception: it’s one of his finest recordings.

We’re nearly an hour into the film before Lustmord’s music makes its first appearance. He makes the most of the time he’s given. “The music comes in [when] we’re going internal,” Williams says. “We’re in [the character’s] headspace. The last third or so of the movie is this journey. It’s basically this one suite.”

The film’s church setting gave Williams the opportunity to cover new sonic ground. He interpolates the familiar melodies of “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms” and “Onward, Christian Soldiers” into his score, performing the organ parts himself. (“Over the years, I’ve actually figured out where Middle C is,” he laughs.) Williams identifies as a dyed-in-the-wool atheist, but his music helps make First Reformed transcendent.

Trinity

In 2012, more than a decade before Oppenheimer, Poland’s Unsound festival commissioned a live Lustmord performance based on the creation of the nuclear bomb. Williams had already been fascinated by the subject for years, having spent time at Los Alamos in the late ’90s. “You pretend not to think about it too much, because you don’t want to think about that stuff,” he says. “But it changed everything. The day before and the day after are totally different.”

Williams further developed that original commission into Trinity, an album bold enough to sample J. Robert Oppenheimer saying, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”—and strong enough to pull it off. The samples and field recordings, taken at Los Alamos and the White Sands test site, are what make Trinity the masterstroke it is. The music feels both apocalyptic and deeply rooted in physical place, a quality Williams was willing to put his body on the line for. “I spent a week in Los Alamos gathering source material, going down illegally, getting thrown out by armed guards, collecting audio,” Williams says. “That was fun. Literally every 50 feet, there’s danger. Guards in white vans passed us a few times, and after a while, two came back and said, ‘What the hell are you doing?’ ‘Sorry, I had no idea!’ We assumed we were gonna get arrested eventually anyway, but we got escorted off the premises.”

Alter (with Karin Park)

2 x Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

In 2021, Williams teamed with Årabrot keyboardist and backing vocalist Karin Park for his most voice-centric album since The Word as Power. (Park also wrote Norway’s 2013 entry in the Eurovision Song Contest. Considered alongside his collaboration with Aina Olsen, a latent pop sensibility in Lustmord’s music starts to emerge.) Park’s vocals were the reason Williams wanted her for Alter, but her keyboard skills were even more crucial for the way the album turned out.

“I’m a big fan of Kraftwerk and Lee Perry and things where it seems very simple, but the choice made is very important,” Williams says. “It seems like simple things are going on, but it’s an aesthetic choice. [Karin’s] aesthetic choice is she goes from this chord to this one. Her choices, the way she plays, and the tempo: Simple is the word. Not in the sense of simplistic, but it’s just right. Not too much, not being flashy, not adding things that don’t need to be added, which is what most people do. Just being in her house as she plays piano, I just shut up and go into a zone listening to it. It was a joy to have her playing keyboards.”

Much Unseen Is Also Here

2 x Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

The new Lustmord album, Much Unseen Is Also Here, feels borne of the same instincts that spat Heresy and The Place Where the Black Stars Hang into the universe three decades ago. It’s long, slow, sprawling, devoid of light, and full of sacrilegious imagery—song titles include the grotesque “Entrails of the God Machine” and “An Angel Dissected,” and a piece from Wayne Barlowe’s series of Inferno paintings graces the cover.

“That’s the connection, if anything, to Heresy,” Williams says. “There’s all this Armageddon, Biblical kind of stuff. Paradise Disowned is specific to that, disowning the whole idea of Biblical paradise. And even in The Word as Power, there’s a lot of references to fallen angels. And there’s a lot of references in this new album to the whole idea of paradise, and those being cast out of paradise. It’s people like me. There’s a subtext in these religions that if you’re not part of it, or you’re different, then you don’t really belong. You’re an outcast. And I kind of riff on some of those things.”

Yet Much Unseen Is Also Here doesn’t feel like a deliberate look backward, nor was it meant as one. Instead, it’s the continuation of an arc, one that Williams, now 65, concedes is past its halfway point: “I’m at the age where I’m not going to be around that much longer. I’m not going to make as many albums. There’s not that much time left.” Much Unseen Is Also Here does bear some of the marks of an artistic late period, but it also feels as vivid and specific as Lustmord’s records ever have.

“With my music as a whole, I try to create a place,” Williams says. “Not literally a place, but psychologically or symbolically, a place that only exists when the music is playing. The music is on, and you enter that space. For me, it’s a really fucking huge space. I try to create a mood that will take you to that place.”