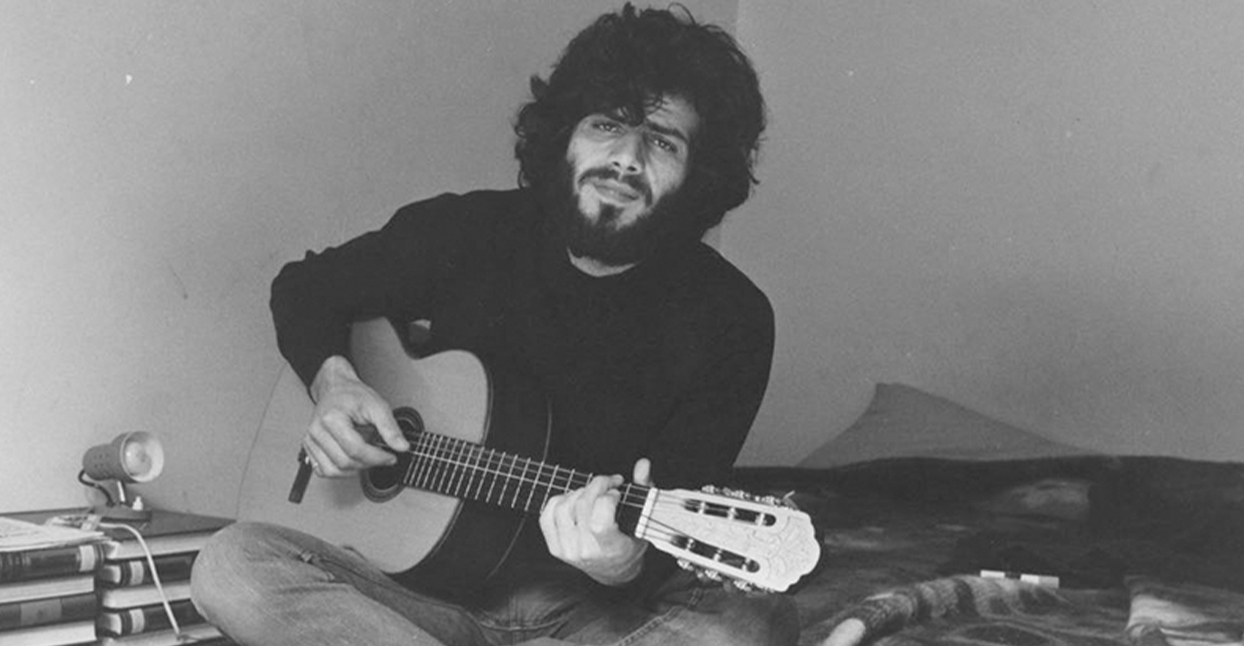

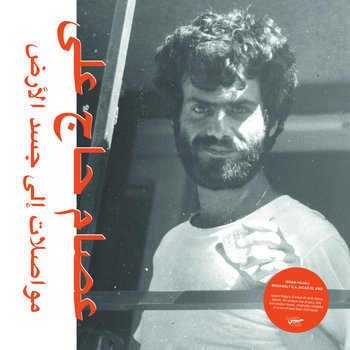

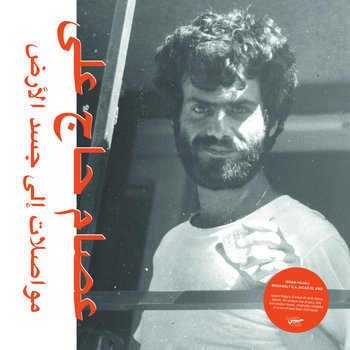

It was the mid ’70s, and Issam Hajali’s world was changing quickly. Hajali was a 19-year-old on the rise: a singer and guitarist in the Beirut progressive rock band Rainbow Bridge, whose first record had charted in Lebanon. He was also a militant leftist who became ensnared in the Lebanese civil war that erupted a year later. By 1976, he had fled to Paris, destitute and unwelcome in his home country.

It was the mid ’70s, and Issam Hajali’s world was changing quickly. Hajali was a 19-year-old on the rise: a singer and guitarist in the Beirut progressive rock band Rainbow Bridge, whose first record had charted in Lebanon. He was also a militant leftist who became ensnared in the Lebanese civil war that erupted a year later. By 1976, he had fled to Paris, destitute and unwelcome in his home country.

“It was very, very hard,” says Hajali today, speaking by phone from Beirut—where he is now a revered musician and songwriter, known throughout the Arab world. “Paris is very difficult for immigrants. It was a strange new environment…it’s very hard to adapt.”

The beginning of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975 was marked by idealism. Long-oppressed lower classes and religious sects (including the Palestinian Liberation Organization, then based in southern Lebanon) found strength in unity against the Western-backed Maronite (Christian) ruling class. In the summer of 1976, Syria invaded on the Maronites’ behalf. Thousands were killed; Beirut was devastated. To escape the danger, Hajali and his wife took flight first to Cyprus, then to Paris. Two years before, he had been a pop musician on the cusp of a breakthrough; now, Hajali was scrounging for work in factories, supermarkets, and anything else he could get. He was able to find housing in an immigrant community, one that turned out to be comprised mostly of musicians. A number of them were from Arab nations, which re-ignited not only his interest in playing, but in his own heritage.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

“Coming into this new culture, from a war, I was asking so many questions of myself,” he says. “You ask yourself about your entire existence.” When he was living in Lebanon, he took the region’s musical traditions for granted, choosing instead to embrace the Western pop vanguard: Peter Green, Joni Mitchell, Weather Report. Now, he was re-experiencing his homeland’s music in a whole new context. “It made me look at my roots in a different way,” he says. “I started looking to traditional music, trying to understand more. I started remembering—and this made a rebirth.”

He poured himself into the music, playing with and learning from his new friends and spending his free time writing new music. The obsession gave him newfound purpose, but it cost him his marriage.

“I said to myself, ‘Why should I stay in Paris?’” Hajali recalls. “I had lost my wife, and [back home] I had to continue something I had started, see where society was going to. But at that same time, I had started preparing my recording.”

Hajali had saved enough money to spend a single day in the recording studio with some of his musician friends from France, Algeria, and Iran, whose names have been lost to time. He does, however, remember the name of Roger Fahr: a fellow Lebanese exile who had become a mentor to him.

They recorded each of the basic tracks (seven of them) in one take, then overdubbed the vocals along with the santur, a dulcimer-like Persian string instrument. The daylong session took place in either May or June 1977—he doesn’t remember precisely. The next day, he said goodbye to his friends, and headed back to Beirut, recordings in hand.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

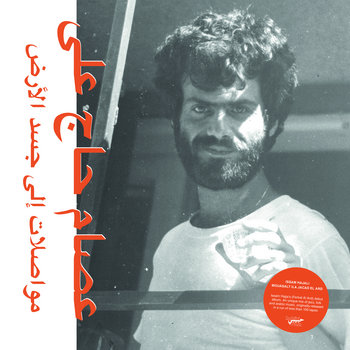

He would title the finished album Mouasalat Ila Jacad El Ard: “Journey to Another World.” Its meaning isn’t as straightforward as it seems. “‘Mouasalat’ has a very saturated meaning,” he explains. “It can mean a way to transport from one place to another; it can mean communication; it can mean returning to the roots; it can mean to connect physically and emotionally with someone.”

The 75 or so cassettes he made of Mouasalat Ila Jacad El Ard mostly went to Hajali’s family, friends, and fellow musicians. They did, however, contain the seeds of his next project, Ferkat Al Ard (“Earth Band”), now regarded as a foundational Lebanese band of the civil war era. (The second of their three albums, 1979’s Oghneya, is highly sought after by record collectors.) He withdrew from political activism in 1980, instead pursuing a more personal musical vision; he remarried, had children and, in the early 1990s, earned a master’s degree in philosophy.

Today, Hajali runs a small jewelry shop in Beirut, bringing his guitar along. He hasn’t performed in years; his musical livelihood comes from selling his compositions to other artists.

In 2016, Jannis Stürtz, Arabic pop devotee and owner of the Berlin-based Habibi Funk Records, tracked Hajali down in Beirut. They talked about the musician’s life and career, and Hajali pulled out a CD-R of Mouasalat Ila Jacad El Ard that a friend had made for him. Stürtz loved it, and was fascinated to hear about its origins as a refuge from difficult times in exile.

“He said, ‘You still have the tape?’” Hajali recalls. “I said, ‘Yes, I think I have it.’ So we found the cassette, and we started from there.”

Though very much of its time, the music is startlingly fresh and visionary even 40 years later. It might not be enough to restart Hajali’s dormant performing career—“Take care of family, take care of shop, work on music,” he says. “That’s what I do.”—but Hajali reveals that he does have a new set of compositions in the works. “I have a big number of fine tunes—real good,” he says. “It’s almost 80 percent done.” The world may yet hear more from Issam Hajali.