High Scores is a monthly column in which Bandcamp profiles a video game soundtrack composer. This month, Casey Jarman talks to Jim Guthrie about his latest game soundtrack for “Planet Coaster.”

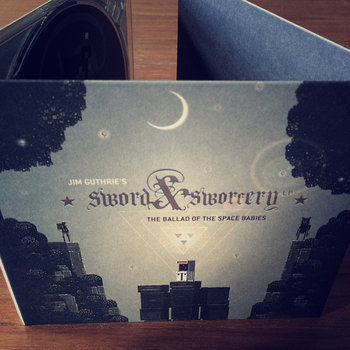

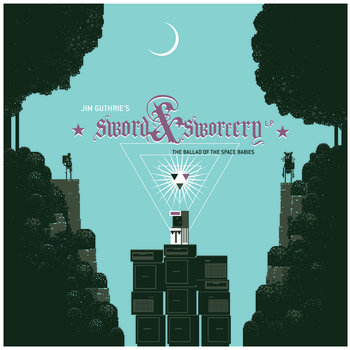

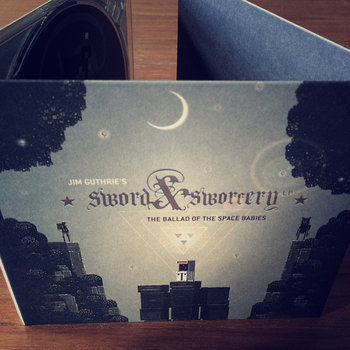

Toronto musician Jim Guthrie’s success story is potentially inspiring to fellow video game composers, even though it’s unusual for the field. His first game soundtrack, for Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery, sold well over 30,000 copies, and the game itself has sold in the millions. But part of the reason for his success is his long history in music; his first game soundtrack was far from Guthrie’s first album. He had been cutting his teeth in indie rock for over fifteen years—in bands like Islands and Human Highway—before his soundtrack success began, and his solo albums had garnered significant critical success in Canada and the U.S. long before he was a household name among indie game aficionados.

But critical praise in indie rock doesn’t always pay the bills. In conversation, Guthrie seems truly humbled by the success he’s had working in games, from Sword & Sworcery to the hugely anticipated Below, to the soundtrack he’s releasing this week for Planet Coaster—a game that has already amassed a huge online community while still in beta. We spoke via telephone in May, and again this month via email.

You’re a bit different from many homegrown game music composers, in that you had a lot of success in indie rock and played in a lot of notable bands before your first game soundtrack, Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery, came along. It sounds like you thought you were just working on this quirky little mobile game at that point. I wonder if you had any idea what a big impact it would have on your career?

I had no idea. I don’t think any of us did. IOS was still a new beast, and the iPad wasn’t even out when we started to make the game. I’d been doing music ever since I was a teenager. I’d had different success levels, but I never really felt like I was making a living, you know? I was fortunate enough to be in some cool circles and make some cool music, and I had some eyes on me, but I never felt like I was making a real living. When the game thing came along, that changed everything.

Compact Disc (CD), T-Shirt/Apparel, Cassette, Vinyl LP

Looking at reviews for Sword & Sworcery in the App Store, the music really gets mentioned over and over again. It really is one of the big things people say about the game. Did that catch you by surprise, that people were really noticing it? Because it’s actually pretty subtle in a lot of the game.

It was a surprise that people took note of the music as much as they did. But at the same time, it was by design. We always sort of couched it as an album you could walk through. I was very lucky: Craig [Adams] was excited about the music I was making and he wanted to feature me as an equal player. My name is front and center, and he really pushed me to the front. I’m super thankful for that. He really loved my stuff, and it showed. I was aware of the profile I was getting from that, but I wasn’t quite prepared for the fact that people would like the music as much as they’d like the game. You could enjoy the music on its own, and people really responded to that.

Translating the game’s musical experience into a soundtrack is kind of a crazy process, because there are loops and stems involved. Were you writing your tunes as stems or writing as complete songs?

Scenes from Planet Coaster, the game.

Yes and no. When you come from the indie rock world, you have a certain kind of person that goes out to an indie rock show and listens to the music. Then you get into games and think it’s going to be a whole different thing. Yeah, people are different, but we’re all kind of the same. These are people who love music and were moved by an experience. There are some clichés in any sort of group of people. Gamers tend to stay indoors more and play more games than the average person, obviously. So you expect a certain level of introversion, but when we go out to showcase the game at a Game Con or whatever, people are so outgoing and so loving and giving—they just want to talk and hang out. The other thing I’m learning, too, is that people in games can drink. You think, ‘Oh, we’re rock and roll, we play bars every night and we drink.’ But man, game people can drink more, I think.

The people who play games, or the people who make games?

The people who make games, I’d say. When I made Sword & Sworcery, I realized that making games really is the same as being in a band: It’s a small group of people—Sword & Sworcery was made by like five people—and it’s people who like to get drunk and talk about their feelings, you know? They’re really funny, intelligent guys who are passionate about what they do and it’s really no different than being in a band. The difference is that when you’re in a band you go out on tour. I toured forever and played all over, but for the last five-plus years I’ve stayed home way more, and I really enjoy it.

Below is a hugely anticipated game with big expectations. Does that change the way you approach the music?

I don’t want to cop out, but it’s another yes and no. With Sword & Sworcery, no one was waiting for it and there was just the pressure that we put on ourselves, which was a huge amount of pressure. There was the time and money pressure: The longer it took you to make the game the more it was costing, the more you were going in the hole. Games aren’t cheap, they can take hundreds of thousands, or even millions of dollars, depending on how big the team is.

Sword & Sworcery was like, ‘Here’s a song and here’s a beat, here’s a melody, here’s a section of the game you’re going to put it in. You’ll walk from here to here and you’ll hear this song.’ In Below there’s a lot more wandering around, so it’s a lot more ambient. The music is really droney. It’s not as memorable in some ways, but hopefully it’ll be memorable in terms of the feeling and the vibe. The thing is, we’ve been working on it for a long time. The music started off being one thing like three and a half years ago, and as we’ve learned what the game is and what the game wants to be, and we see what we’re responding to as we throw all these ideas at it and keep one or two—you go through that process and over the years it develops into something that you weren’t really anticipating, but it’s still sort of a surprise.

I’m sure when you work on a piece of writing, you think it’s going to be one thing and it sort of changes. When you don’t fight it, it can be a lot of things. But it’s also very stressful: It’s not what you first anticipated but you know it’s the right thing to do in terms of the art of it and the atmosphere you want to create. So yeah, I think it’ll be the most non-music music soundtrack that I make. It’s not totally experimental or devoid of melody and notes, but it’s a lot different from what I would normally do. The game doesn’t want beats. It’s been interesting to come up with the most musical version of non-musical ambience.

That seems like a cool challenge. It must be kind of neat to be pushed in a direction where you’re not sure where it’s going.

It’s terrifying, in a sense. But I’m pleasantly surprised and pleased with it. I know, one-hundred percent, that people are going to say about the music, ‘Yeah, this is cool, but it’s not Sword & Sworcery.’ I’m totally ready for that. But it doesn’t really change the way I do things. I can’t let that dictate what we do with this game. It’s a totally different thing. That’s not from an ‘I’m an artist’ place. It would be ridiculous for me to put a really fat beat in this game. It’s a humbling experience to listen to what the game is telling you.

You’re about to release You, Me & Gravity, the soundtrack to Planet Coaster, a theme park building game that is really open-ended and lets players kind of go crazy. It’s a different kind of game for you, and it’s also a collaboration with multi-instrumentalist JJ Ipsen. How did you and JJ start working together?

JJ is an old friend and we’ve played in bands together over the years. At some point, early on in the project, I asked him to lay down some keys and other ear candy on a track. He added so many great sounds that we just continued the collaboration.

Is there a difference in approaching an open-ended, sandbox game like this one, rather than soundtracking something more linear or tracked?

Well, to be honest, we just wrote cool tunes that fit the relaxed and uplifting vibe we were asked to create. It was the audio team at Frontier that really implemented the stems in a creative way. I still haven’t even really seen all of the amazing things they’ve done with it.

Some of the music is very contemporary pop-oriented (especially the opening track, “The Light In Us All”), and some of it sounds very much from the folk tradition, with a lot of string instrumentation. It has an organic sound, overall. Can you talk about the vibes you wanted for this music?

Sure. “The Light In Us All” was actually the first track I wrote, and it was going to be a little different right from the start, just by virtue of being the theme. We wanted it to be catchy and very upbeat. The group vocals were supposed to take the hook and inject the energy and the inclusiveness we wanted to have in the game. The rest of the music was just supposed to maintain a welcoming feeling, but in a more relaxed way. We decided early on that is was going to be mostly acoustic instruments, and we also wanted to evoke a sense of nostalgia and subtle emotion into it. We didn’t want it to be sad, but we wanted the feeling to be somewhere between missing something and being grateful for having found memories.

The track direction, by Jim Croft, also included some cooler indie tunes that totally spoke to me, having made a few singer-songwriter albums myself. That’s what drew me—and JJ, who played on my album, Takes Time—into the project . We already sort of lived in that space, so this was a dream job, really.

If you could rework the music for one classic game—not because the original music is bad, but because you’d like to bring something different to the table—what game would you take on and how would you approach it?

I would take one of the most famous scores ever—Super Mario Bros.—and make it super emo, because it must be so intense for Mario.

—Casey Jarman