When the No New York compilation was released at the end of 1978, a line in the sand was drawn on 14th Street in Manhattan separating downtown New York from the rest of the city, if not the entire world.

Only a handful of years after the Ramones redefined rock ‘n’ roll from a low stage at a Bowery dive, the groups on No New York—Teenage Jesus and The Jerks, Mars, DNA, and the Contortions—were shedding the skin of rock’s corpse and reanimating it with a feral dissonance that served as a Keep Out sign for those in search of the expected thrills. Even though punk was still a caterwauling newborn, no wave set about smothering it in the crib and setting the house on fire.

The music industry wasn’t completely oblivious to no wave’s dark shadow. Brian Eno—fresh from producing a run of lauded David Bowie albums—selected and recorded the groups showcased on No New York, granting them a degree of validity that the industry had to respect, if grudgingly; these bands bucked against its profit-driven nature. While suburban America didn’t jive with the nihilistic frenzy of New York’s finest, within the confines of the city itself, a revolution had been sparked.

History has a way of reducing incisive moments into bite-size morsels, easily digested and made palatable for the masses. It’s no surprise that an inherently anti-commercial scene such as no wave was small and localized, but old narratives need to be re-evaluated on a consistent basis. In late 1970s Manhattan, there were more than just four bands stripping rock down to its chassis and pounding on the skeleton. Not all of the downtown groups were wild-haired maniacs blitzed on cheap booze and amphetamines; some of them were regular people that worked day jobs. As Chris Nelson from Information tells it, “I had sufficient office work experience to know that the Computer Age was coming. I said: someday all music will be information.”

Evolving alongside the more recognized groups (though still obscure, they had notoriety on their side), Information, Blinding Headache, and Mofungo showed a way out of no wave’s relentless cacophony. Fundamental to their approach was a wry sense of humor coupled with a commitment to the absurd, and turning the sound of nontraditional instruments (steel boiler, sound toys, street finds) into freeform jangle, juddering improv, and howls of anguish.

Members of this cohort had a direct influence on the nascent no wave scene. Most of the original lineup of Information—Nelson, Jim Sclavunos and Philip Dray—were “staff members” of the influential NO Magazine, whose tagline “Instant Artifact of the New Order” placed them in the center of this burgeoning micro-movement. Information was NO Mag’s house band, and appeared on a flexidisc that was included with its final issue. Nelson may even be the one responsible for the term “no wave,” as one of his graphic designs featured a surfer with a printed plea to “make no new waves.”

Although only a hundred or so copies of each issue of NO were printed, its aesthetic did, indeed, make waves. Both Nelson and Mofungo’s Robert Sietsema jumped aboard New York Rocker, the city’s premier music-oriented underground paper. Nelson was the graphic designer while Sietsema snapped photos and wrote about bands. The mixing of creative and professional life suggests that the social aspect of this micro-scene was what truly drove it. Instead of shooting pool or watching football, these friends played music. As Sietsema explains, “We would get together and make up songs and have a blast. We wanted to associate with each other, finding music to be a non-embarrassing way to socialize. Let’s face it—we were not going to dinner parties or Broadway shows or Carnegie Hall or whatever normal friends do. The expression of our friendship was the music.”

Rick Brown had arrived from Delaware to study at NYU, but was soon bitten by the punk bug. In addition to publishing Beat It! zine with Julia Gorton, Brown wanted to make some noise himself.

“Pere Ubu at Max’s Kansas City was mind-blowing. Here’s a guy yelling and banging on a piece of metal and there’s a guy twiddling knobs and making weird sounds. There’s a way into this without learning chords on a guitar. I don’t have to do that, but I can do something. That was in the back of my head when I met Willie Klein and Jim Posner. They were both guitar players and we started playing together in the basement of our dorm. At first, I was banging on an abandoned boiler. Eventually I got one drum, and then another.”

Brown’s first band, Blinding Headache, used anything within reach to make music: battery-powered amps, foot-switch-triggered tape machines, resonant materials found on the street, a dressmaker’s dummy repurposed as a cymbal stand. Even the manner by which Blinding Headache rehearsed was cost-effective: after delivering the Spanish-language newspaper El Diario from a warehouse in Connecticut, the band would load their minimal drum kit and portable amps, drive to “Sewer Beach” near Stuyvesant Town, back up the truck to the East River, and blast through their set. Needless to say, Greenpoint was not quite prepared for this racket. As depicted in photographer Julia Gorton’s Nowhere New York book, the downtown scene teetered between gritty tableaus of urban squalor and intimate, inventive art-making sessions.

This society of friends even had their own underground club on St. Mark’s Place, the Black Hole, later called Stinky’s after it moved locations. “We created a club that lasted for a month in the basement,” relates Sietsema. “Every Saturday night we would have a party and eventually bands played there.”

Mofungo was the last to form, emerging around the period that No New York was being unleashed. With Jim Posner and Willie Klein coming from the recently extinct Blinding Headache, the revolving personnel coalesced with the addition of Sietsema (playing one of Posner’s modified three-string bass guitars), followed by Jeff McGovern on drums and Seth Gunning on keys. Soon, a plan was hatched to feature this trio of like-minded bands on a homemade compilation to be released on cassette, which allowed participants to include over an hour of material, far beyond the 44 minute length limit of a standard LP. That compilation, known as Tape #1, is now ripe for rediscovery on Bandcamp courtesy of Blinding Headache/Information (and currently 75 Dollar Bill) drummer Rick Brown.

One of the most striking aspects of Tape #1 is how much of the material completely ignores rock ‘n’ roll history. The way Information rushes through tuneful fragments such as “Let’s Compromise” and “Renovation” comes across like hastily scribbled manifestos under the camouflage of song. (Yo La Tengo covered “Let’s Compromise” on its sophomore album New Wave Hot Dogs, which also sported a Robert Siestema photograph on the front.) On “Info’s ’10-4, 10-4,’” the group dips into mutant disco like they’re auditioning for Lizzy Mercier Descloux’s backing band. In Mofungo’s world, Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band are the Rolling Stones. “Chicken Gas” mimics squawking poultry while the band syncopates awkwardly; “I am from Jupiter and I am going to kill you” features a recording of Sietsema’s young neighbor’s whispered threats. As Sietsema says, “We didn’t know that we couldn’t write songs, which was a real blessing.”

With its ominous bass riff, plodding rhythm, and serrated guitar lines, Blinding Headache’s “(I) Just Can’t Help It (I’m a two-stroke engine)” betrays the influence of Teenage Jesus, but the majority of their songs are impressionistic fragments that attempt to decode the confusion of city life. Blinding Headache wasn’t filled with rage, they were bursting with questions. The final track gives you an amusing little peek into the hands-on nature of the making of this document.

While Blinding Headache and Information had relatively short lifespans, Mofungo flourished during the 1980s. After their debut album, End Of The World, came out on cassette, Mofungo released six albums, finally calling it a day in 1993. Nelson joined the band in the mid-’80s, as did noted composer and instrumentalist Elliot Sharp. By the late ‘80s, Mofungo was on SST and they had become something like elder statesmen of the no wave diaspora. At this point, the scene had wound its way out of the Lower East Side, finding a second home just over the Hudson in New Jersey, at Hoboken’s storied club Maxwell’s.

With The Scene Is Now, Philip Dray, Jeff McGovern, and Chris Nelson continued to refine their collective style of subversive pop. Although Nelson is the sole remaining original member, the band is still playing shows and putting out new music.

After Mofungo called it a day, Robert Sietsema transitioned into a career as a restaurant critic for the Village Voice. (He currently writes for Eater.)

The following downtown New York groups traversed the same cracked sidewalks as the bands on Tape #1, sharing bills and aesthetic concerns, demonstrating how no wave reinvigorated a founding tenet of punk—making something new out of nothing, and making “nothing” mean something new.

Theoretical Girls

Theoretical Record

Spearheaded by mercurial composer Glenn Branca and composer and conceptual artist Jeffrey Lohn, Theoretical Girls exposed Terry Riley’s minimalist innovations to the primal roar of rock. Theoretical Girls also featured visual artist Margaret de Wys on keyboards and drummer Wharton Tiers, soon to be engineering sessions for Sonic Youth, Y Pants, Dinosaur Jr., and more. Theoretical Girls combined the brute force of the Ramones with a conceptual framework that nodded towards their high-art training, resulting in a powerful hybrid that manifested as sophisticated punk rock. The pure squall of “Contrary Motion” was surely a reference point for Sonic Youth and the many noise rock bands to emerge from the depths of downtown.

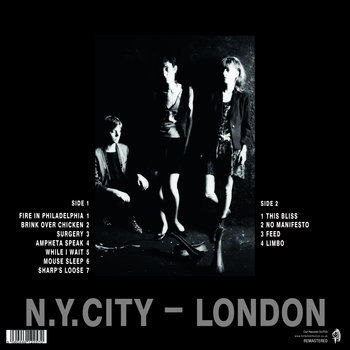

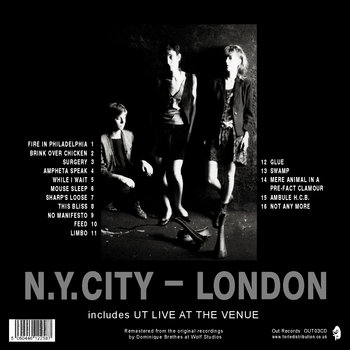

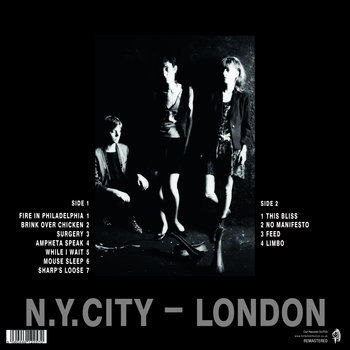

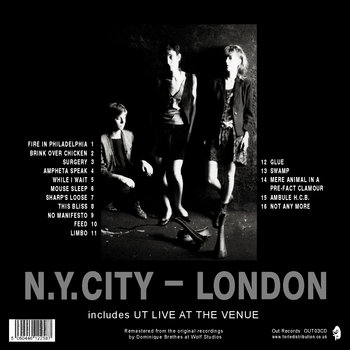

Ut

Early Live Life

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Despite their uncompromising music, Ut has led a remarkably fruitful existence. Founded at the tail end of 1978, the three women of Ut carved out a space for themselves in the crowded NYC scene before splitting town and heading to London, where they found kindred spirits in The Fall and The Birthday Party. After breaking up in the early ‘90s, they reformed in 2010, displaying the same adherence to uneasy listening.

V-Effect

Stop Those Songs

Vinyl LP

Post-Information, Rick Brown, seeking to continue challenging himself on a musical level, joined V-Effect with Ann Rupel and David Zonzinsky. Alongside bands like Curlew, V-Effect slotted into a downtown scene that treated genre like gumbo, stewing jazz, punk, improvisation, and musical traditions from outside the U.S. together to create a new cosmopolitan sound. V-Effect found some success in Europe, where its Rock In Opposition-indebted style connected with sympathetic ears, including Fred Frith who joined them on stage and assisted in the studio.

Circle X

S/T

Vinyl LP

Circle X came screaming into existence after original Louisville punks the I-Holes and No Fun broke up. In 1978, the band headed north to find fame, fortune, and fatalism in the big city. Just as they were making their mark upon the underground scene in New York, Circle X was lured away to France for a year, playing shows, recording, and ultimately returning to New York after being forced to cancel a tour opening for Bauhaus. From there, Circle X’s music progressed at a rapid pace as they took over a storefront on Clinton Street and dove into a dark, pulsating creative well, sculpting their own form of experimental post-punk.

Circle X shows were more like occult urban rituals, with crucified singers, monstrous handmade puppets, exploding cow brains, naked dancers covered in unidentified powders and punishing waves of rhythm and noise. With such a forbidding presentation, Circle X was regarded with a mixture of fear, envy and curiosity. As guitarist Rik Letendre makes clear, “In the gutted areas of the Lower East Side, there was a symbol painted on either side of the doorway. It was a box or circle with an X through it. That was a signal to the firemen: If that building was burning, let it go and save the others around it. Let it burn to the ground because nobody’s in there. People thought we were nihilists, but our trip was, ‘Let’s wipe the slate clean.’” Circle X glimpsed the possibilities in the crumbling infrastructure they were surrounded by; to them, it was an invitation to build something beautiful in the ashes.

Y Pants

S/T

A recent exhibition laid bare what a force Barbara Ess was in downtown’s creative community. Besides her pioneering multimedia publication Just Another Asshole, Ess was an unsung architect of the no wave scene. After assaulting ear drums with romantic and creative partner Glenn Branca in the Static, Ess pivoted away from noise to revel in the domestic clatter and chime of Y Pants. Like many participants of the no wave scene, all of the members of Y Pants were visual artists—drummer Virge Piersol was a member of the Colab collective while keyboardist Gail Vachon made films.

Eschewing the usual rock instrumentation, Y Pants employed toy piano, ukulele, Casio keyboard, stripped-down percussion, electric bass, and, most importantly, their overlapping voices, to construct off-kilter songs that addressed concerns close to home. The first lyric on their lone LP—“Don’t be afraid to be boring”—is great advice, but not something that Y Pants ever had to seriously contend with. On the debut EP, they toss off a Rolling Stones cover (“Off The Hook”) that challenges Devo’s take on “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” for iconic status.

Ess also helped found the revolving feminist performance collective Disband, who dispensed of music all together, by layering their voices into a mosaic of declaration, narration, chanting, and singing, with occasional clapping or foot-stomping as accompaniment. Disband’s live recordings are like a punked-out take on the barbershop quartet, proclaiming poetic screeds about sexual politics and city living to the point of discombobulation, and, if all went well, enlightenment.

Before Ess passed away, it was rumored that Y Pants reunited every year for each of its members’ birthdays. Paying allegiance to the interior landscapes explored in their music, Y Pants performed only for themselves. For a regular band, this gesture could come off as elitist, but for Y Pants it aligns with their original purpose: performance is secondary to the feeling of communion, of creation.

No one ever said that living in New York was going to be easy, so these artists went to great lengths to make it interesting. Tape #1 may have been intended as a mere snapshot in time—a Polaroid shaken vigorously—but over four decades since it came into being, it still resonates with a singular vibration.