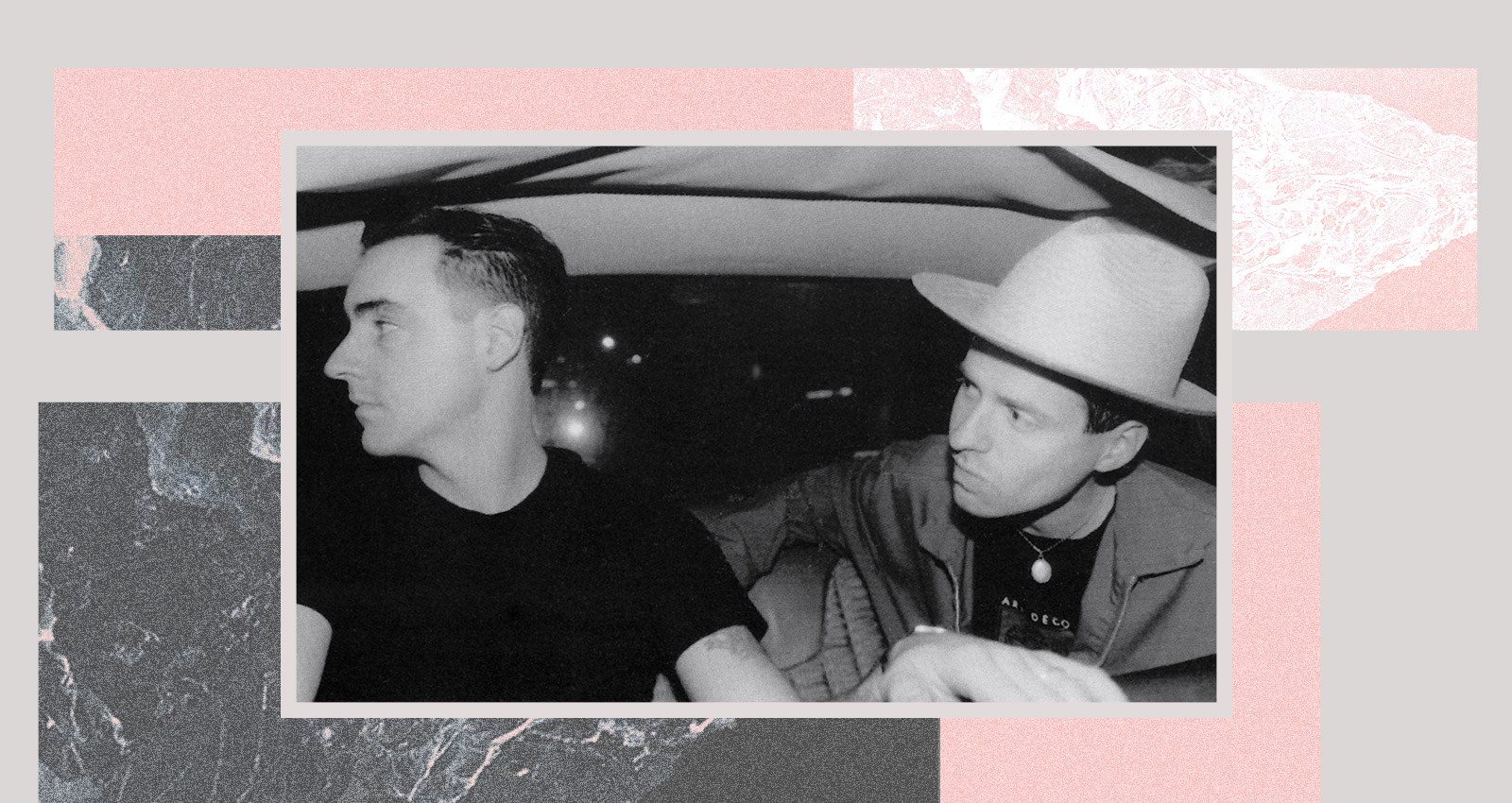

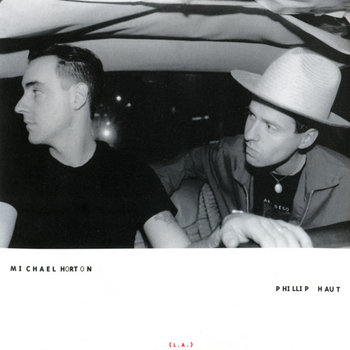

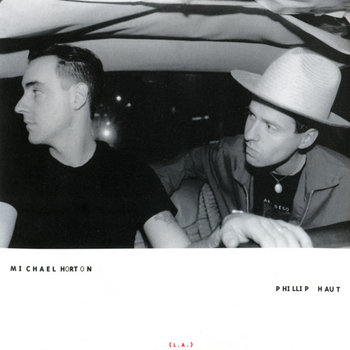

In conversation, Michael Horton and Phillip Haut have the noticeable easy rapport of two longtime friends. They also know how to balance each other out; speaking from Haut’s studio near downtown Los Angeles, Horton talks at a quick, breathless pace, while Haut delivers his recollections with an easygoing swing. Both of those qualities—the camaraderie and the complementary dynamics—are at least in part owed to the fact that they’ve known each other since the late ‘80s, when they founded Supercollider in Long Beach.

Writing songs that fused minimalism and post-punk with sampling and sequencers, and lyrics inspired by modernist poetry, Supercollider weren’t just unique in that era of Southern California, dominated by the final wave of hair metal and the homegrown hip-hop explosion, but almost anywhere in the U.S. (The only comparison that comes to mind is to the equally far-flung and underappreciated UK band Disco Inferno, and even that is a bit of a stretch.) Horton had spent his early years playing in Orange County punk bands while Haut, younger by a couple of years, studied percussion at college in his native Virginia before heading to L.A. in the mid ‘80s.

“When I was about 21,” remembers Horton, “I had joined a band for a short time, sort of R.E.M., Smiths [style]. Philip responded to an ad of ours in 1986. I’d read about sequencing and sampling, and just liked the idea of very constant timekeeping—a very ‘non-argumentative’ sound source to play against. So I bought a sampler, and Philip and I started writing Supercollider songs in 1988.”

The duo’s first formal track, “Primary,” was already in place that same year. Horton credits artists like Sonic Youth, Joy Division, Philip Glass, and Steve Reich—as well as visual artists like Ellsworth Kelly and Donald Judd—as inspirations; the resulting combination of stark, austere guitar patterns and his serene but still emotional singing reflects those influences, as does Horton’s willful defiance of verse/chorus/verse song structure.

“I was reading a lot of e.e. cummings, reading a lot of the Beat poets,” he recalls. “I just wanted to strip things down, play with the sound of words, break them up, and pull as much meaning—even if it was a little obscure—out of three-or-four-word lines to have little surprises as the song unfolds.”

Haut, meanwhile, concentrated not only on percussion, but also on learning the vagaries of the then still-new technology with which they were working. “I was the one who had my hands on the sequencer, but [Horton] was really writing the parts,” he says. “In programming the equipment, you can discover things, and changes and other parts can be added. The process of programming one idea can inspire other ideas. A lot of it was more serendipity than it was actual vision. We’d find out what sounds something can make and put them together and then kind of go from there.”

They began submitting their initial cassette recordings to one record company after another only to be met with a total lack of interest—until a remarkably lucky break arrived in the form of Emigre Records, a near-bespoke side project of the famed font and design firm founded in Berkeley in 1984. Emigre’s Rudy VanderLans took to Supercollider’s music, releasing both their self-titled debut in 1991 and a follow-up, Dual, in 1993, as well as working closely with the band to create striking cover art for those efforts.

The 1991 debut has recently been remastered and rereleased by the duo, the first in a planned series of reissues and archival recordings; hearing songs like “Primary” and “Aluminum” again with fresh ears makes for vivid listening. Some of the band’s and VanderLans design ideas can’t fully translate to the digital realm—the original CD booklet was only a ⅔-size sleeve, showcasing the physical CD itself in a way few such releases did at the time—but the striking cover art has literally ended up in a museum.

“I liked the idea of those thin and thick stripes just because I saw our music in that way, the positive and the negative space,” remembers Horton. “Rudy liked that idea, and of course he did what Rudy does, which is make everything grey. A poster of that [artwork] is actually in the L.A. County Museum of Art, in their decorative design collection.”

Horton and Haut never formally broke up the band, but after Dual, they felt they weren’t getting enough traction for their work, and maintained a friendship while pursuing individual paths in life and music—appropriately enough, both became graphic designers. And while they’ve recently reactivated their Supercollider partnership, they’re planning to take things as they come, though the possibility of new recordings under the name are very much part of the plan.

“I think what we did with samplers is a lot more like what’s happening now,” concludes Haut. “Because I see a lot of people now working with loop pedals and things like that—just using sounds as musical parts.”

“I want to play live again,” Horton says, “because I think that’s the only way we’re going to build momentum and expose people to the music in a visceral sense. Because I think it shows them that you’re out there: two guys playing instruments, even though we’re also against this machine that’s unrelenting in repeating these sequences on time.”