The sun is going down in Cairo, but the action on Misr Wel Sudan Street shows no sign of abating. Puffs of smog dissolve into the winter air. Cars honk their horns, snaking through the narrow but busy thoroughfare. The call to prayer billows from a mosque over scratchy loudspeakers. Men sit in a nearby cafe sipping black tea and playing backgammon.

Across the street, two teenagers kick back in plastic patio chairs next to a tire shop. Amid the bustle, no one pays attention to the abandoned music shop that sits directly behind the kids’ perch. In faded gold letters, a sign above the store says “Maestro.” The windows are caked in dust, the front alcove locked up by a gate. When I peer through the metal grates, I see a blackened void of grime and garbage. It doesn’t look like much now, but to some it’s a historic place: Salah Ragab’s old music shop.

Many people in the West don’t know the name Salah Ragab, but in Egypt, he’s one of the greatest jazz musicians who ever lived. Coming of age during a rich period in the country’s history, this late, great bandleader and drummer (who died in 2008) was the first musician in Egypt to assemble a proper big band orchestra.

His group was called the Cairo Jazz Band, and from the late ’60s to the early ’70s, they mastered an original, bombastic style of Middle Eastern swing, performing in some of Egypt’s biggest concert halls and laying down recordings that still sound fresh today.

Ragab was an officer in the Egyptian army when he put the Cairo Jazz Band together. With the help of friends and collaborators, he’d hand-picked musicians to fill the ranks of his jazz orchestra, then drilled them for months to teach them how to swing. In later years, he recorded and performed with a range of jazz stars, including Sun Ra and his intergalactic Sun Ra Arkestra.

Today he’s an obscure figure, but his peers regard him as a pioneer, paving the way for future jazz musicians and helping introduce Egypt to jazz. “He was a great musician, visionary and adventurer,” says Amro Salah, director of the Cairo Jazz Festival, held every year in Egypt’s capital. “He was a lovely person and a great icon for someone like me.”

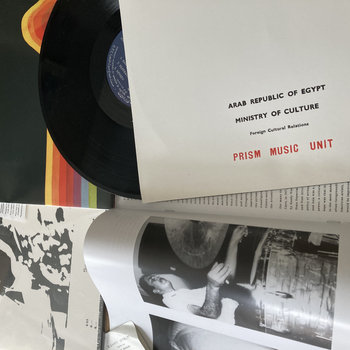

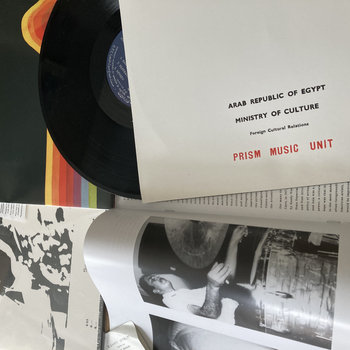

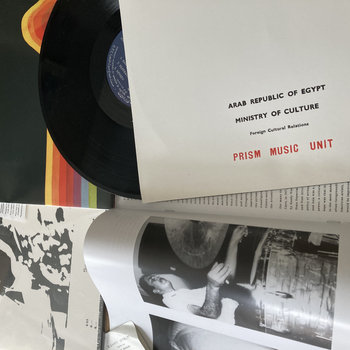

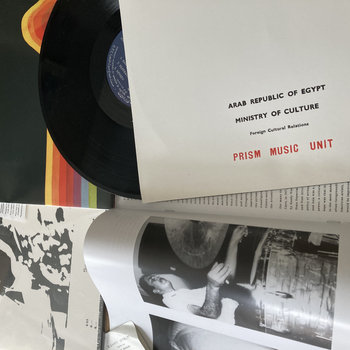

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD), 2 x Vinyl LP

The Maestro music store might be long-forgotten, but Ragab’s legacy lives on in his recordings. In 2006, the Sun Ra-affiliated U.K. label Art Yard collected Ragab’s work with the Cairo Jazz Band in a compilation entitled Egyptian Jazz. Put to tape in the Cairo suburb of Heliopolis between 1968 and 1973, the recordings are lo-fi, but the band sounds muscular and innovative, blending black American jazz with Egyptian folklore and Islamic tradition.

Perhaps the group’s catchiest song is “Egypt Strut,” which borrows from a popular Egyptian folk melody, turning it into a funky blues number. Even more stunning is album opener “Ramadan In Space Time.” The song’s minute-long intro opens with a chorus of voices and a slow rhythm tapped out on a tabla—Egyptian listeners will recognize it as the sound of the musaharati, the man tasked with waking up fellow Muslims in the early morning hours to have a daily pre-dawn meal during the holy month of Ramadan. The voices in this case sound deep and cosmic, as if beaming not just from a night’s sleep, but from another galaxy altogether. Then, the quiet mood breaks and the orchestra launches into an attack: drums, piano vamps, elephant-like roars of trombone and trumpet, and the musaharati rhythm keeping pace beneath a gargantuan groove.

“He had the sound in his head, and he was able to translate this sound to life, which is not usual,” Rashad Fahim, a celebrated Egyptian jazz pianist and longtime friend of Ragab’s. “In general, drummers like to learn the rhythm note-by-note, and they play it like they study it. But Salah was playing from inside.”

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD), 2 x Vinyl LP

Born in 1935, Ragab grew up in Hadayek El Kobba, a Cairo neighborhood a short drive from downtown. He had two brothers, three sisters, and he grew up in comfort (his father, who died when Ragab was three, was a pasha, a title bestowed on high-ranking officials and military commanders in the Egyptian monarchy). Today, the family’s five-story, Belgian Colonial-style mansion still sits right behind the Maestro shop on Misr Wel Sudan Street, and it looks like a blast from the past compared with the newer concrete apartment blocks that run down the opposite side of the street.

Ragab’s grandson, Ahmed Aladdin Kassem, grew up hearing stories from Ragab and now serves as the keeper of his grandfather’s jazz legacy. When I meet with him at a hotel cafe in Heliopolis—not far from where Ragab had gotten his military training, and later whipped his jazz band into shape—it’s easy to see the powerful effect that the composer had on him.

“He was calm, he was elegant, decent…but when he gets nervous about something, you have to stay away from him. He has a way of looking—you know when you do something wrong,” Aladdin Kassem says, weaponizing his eyes and darting them in my direction to emulate his grandfather’s glare. “A soldier, you know? The military way.”

Ragab came from a family of soldiers, and after graduating from school, he followed in his uncles’ footsteps and took up studies at Egypt’s Military Academy. Serving in the Egyptian army from 1957 until the early ’70s, he was present during some major conflicts in modern Middle East history. In the 1960s, he was sent to North Yemen to fight with Egyptian forces on the side of the Yemen Arab Republic; he also commanded a tank division in the 1967 war with Israel. At one point during these conflicts, according to Aladdin Kassem and Ragab’s friends, his commanders incorrectly determined he’d been killed in action, and he ended up stranded in the desert, forced to make a death-defying trek back home on foot.

Ragab first got into jazz when he heard vibraphonist Lionel Hampton on an English-language radio station in 1954. Soon, he and his wife were spending nights on the town, tapping their feet to the beat of jazz and blues in trendy clubs and cafes. The most popular artists at the time were Arabic singers like Oum Kalthoum and Abdel Halim Hafez.

But according to Alex Lubin, a professor of American Studies at the University of New Mexico, jazz shows were also quite popular at the time, in part thanks to a growing expatriate population of African-American intellectuals and musicians, who were drawn to Egypt for its Islamic institutions and for the pan-African, anti-colonial politics of president Gamal Abdel Nasser.

The seeds for Ragab’s big band orchestra were sown when the budding drummer joined a group put together by a Kansas City saxophonist named Osman Kareem. Also known as Mac X. Spears, Kareem had spent years touring the United States with bebop pianist Bud Powell, but he’d left the country after growing disillusioned with American racism and found his way to Cairo, where he began studying Islam at the prestigious Al-Azhar University while teaching music lessons on the side.

“He decides to form a quartet, and someone recommended to him that he choose the drummer from Gamal Abdel Nasser’s military band—and that was Salah,” Lubin says.

Kareem and Ragab started playing shows around town, and over the years they ended up becoming close friends and collaborators. Unfortunately, Kareem ended up having to leave the country due to rising anti-American sentiment in the months surrounding the 1967 Six-Day War. But Ragab kept pushing forward with his dream to create Egypt’s first big band. In 1968, he was appointed head of the military music department, and with thousands of musicians under his command, he hand-picked a group of 20 and dispatched them to a special “jazz house” on the Heliopolis military base where the music department was headquartered. Ragab’s recruits had no idea how to play jazz, but apparently the commander didn’t give them the option to back out.

“He ordered all the soldiers to play those jazz tunes, and if they don’t do it, he told them that he would put them in prison,” Fahim says.

Hartmut Geerken, a musician and friend of Ragab’s—who at the time was working for the Cairo branch of the Goethe-Institut, a German cultural organization—helped Ragab put the ensemble together. A Czechoslovakian bassist and teacher named Eduard “Edu” Vizvari also worked with them, and together they spent months bringing the Cairo Jazz Band to life. Over the span of a year, they taught lessons on jazz history and walked the musicians through rudiments and arrangements written by some of Geerken’s colleagues back home.

“We started not with the whole orchestra but in small groups—the trumpets or the trombones and so on. We started to play very simple things, swing or even Dixieland,” Geerken recalls. “Slowly, slowly, with the help of Edu Vizvari and Salah and myself, we bring [the band] to a point where it sounded [like] real jazz. But it was a long process of learning and teaching.”

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD), 2 x Vinyl LP

The Cairo Jazz Band played their first concert in February 1969 at Ewart Memorial Hall at the American University in downtown Cairo. The set list included originals by Ragab, Geerken, and Vizvari, as well as takes on standards by Dizzy Gillespie, Count Basie, and others. The public response was positive, and over the next four years, they went onto play well-attended concerts at venues like the Cairo Opera House and the University of Alexandria.

As regional tensions flared, Ragab occasionally had to be cautious about his interactions with his foreign friends. A few years into the band’s run, the maestro was called in by the security services for questioning about Geerken and Vizvari. Once, he was forbidden from making contact with Geerken, and the two had to arrange a secret rendezvous in the desert to plan an upcoming show.

“We didn’t meet in Cairo, but we arranged in some hidden way to meet at, let’s say, kilometer 43 on the desert road. We met there and we talked about the program and which titles we will play,” Geerken recalls.

According to Fahim, the Cairo Jazz Band’s illustrious run came to an end with the onset of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. By then, music programming was eclipsed by more pressing strategic and territorial concerns. Ragab retired from the military after the war, eager to focus on his music, Aladdin Kassem says.

In his post-military years, Ragab continued to be a fixture of Egypt’s music scene. In the early ’80s, he toured Europe with Sun Ra; he also recorded an album with the Afrofuturist composer, titled The Sun Ra Arkestra Meets Salah Ragab In Egypt. In the ’90s, Osman Kareem made return visits to Cairo to play shows in Ragab’s combo, which featured Fahim and other local jazz heads and performed regularly until Ragab passed away in 2008.

When he wasn’t gigging, Ragab ran his Maestro music shop, and in his off hours he relaxed in his private study, rolling cigarettes, sipping coffee, and listening to his collection of jazz CDs and tapes. Aladdin Kassem remembers Ragab fondly; one day, the jazz legend came into his room and caught him listening to a cassette of trumpeter Herb Alpert, and handed him a Miles Davis one instead.

“We need to teach Egyptians about jazz music. One by one, step by step,” Aladdin Kassem says. When it comes to Egyptian jazz, there’s no better place to start than with Salah Ragab.