It feels cliché at this point to describe the music of the U.K. group Revolutionary Army of the Infant Jesus as a “shared secret,” but in the early ’90s, that’s exactly what it was. Their albums seemed to materialize out of nowhere. You heard about them from a friend who heard about them from another friend, who happened to have a burned CD that they’d loan you for a week so you could make your own. (To wit: I was a fan of the band for decades before I knew what the cover of their haunting 1987 masterpiece The Gift of Tears even looked like). Not only were there no interviews, the band wasn’t even written about, not even by the fledgling alt-music press. If you travelled in Christian circles, as I did, they had an almost occult aura; their music drew on Christian and religious themes, but their name came from director Luis Buñuel’s film That Obscure Object of Desire, and they could just as easily have been witches as saints. The lack of any kind of public presence only caused their eerie mystique to grow.

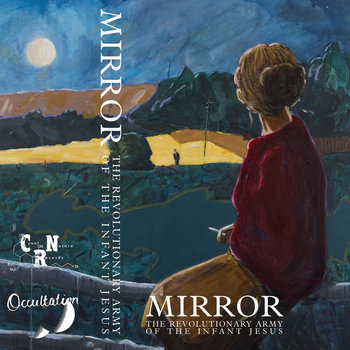

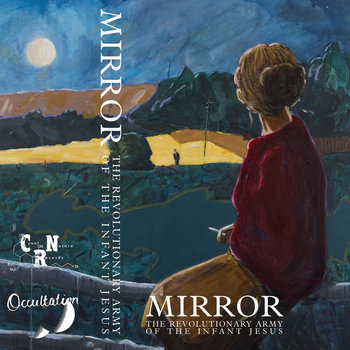

Listening to the group’s two albums—the only works to their name—only added to the mystery. Mirror, from 1991, recently reissued by Occultation Records, felt like the soundtrack to some unsettling ritual, taking place in a deep wood late at night. Their songs were built around ominous, chant-like vocals, full of chilling acoustic guitars, baleful, minor-key synths, and melodies that drew heavily on Medieval modalities. Nowadays, we might call their music “folk horror;” in the ’90s, it felt almost forbidden.

And then, just as quietly as they appeared, they vanished. Even after the arrival of the Internet, information about them was scant—just a few bare-bones fan-created websites (which usually employed white text on a black background), which generally contained brief summaries of their history with no concrete details. But all of that changed in 2015, when the band reappeared after a 20-year absence with Beauty Will Save the World, a record that is just as gorgeous and harrowing as any they made during their initial run. The news of their reactivation travelled much in the same way their music did the first time: via emails from friends, or posts in small-ish Internet interest groups. And while it’s certainly easier to learn about the band now—they even have a Facebook page—their music has retained all of its spectral beauty and glorious ambiguity. We sat down with Jon Egan who, along with Paul Boyce and Leslie Hampson, form the group’s core membership, to discuss their history, and how creating mystery isn’t just a PR stunt—it’s the very core of their art.

Vinyl LP, Cassette, Compact Disc (CD)

One of the things that comes up when talking about your music is the fact that the band always seems shrouded in mystery. But when I read other interviews with you, you’re very clear about the fact that you never set out to be a ‘mysterious’ band. Where do you think this reputation came from?

I think it came from reticence. We always felt a little bit tongue-tied. We struggled to answer questions about our music. It seemed to be something that could only be articulated through the music itself. I think so many artist interviews are really just marketing, so the answers aren’t necessarily authentic or true or explanatory—they’re just part of a marketing exercise. All of that just felt intrinsically uncomfortable for us. Ideally, the work should speak for itself. It shouldn’t require any kind of explanation from us.

It’s especially complicated given the kind of music you make, where mystery is so central. It’s hard to get too deep into talking about what you do without feeling like you’re trying to ‘lift the veil’ or something. Even though the ‘elusive’ nature of your band wasn’t some grand plan, do you feel like there’s a degree to which having a level of anonymity enhanced people’s experience with your music?

Yeah, I think it did. ‘Mystery’ is a word that means a lot to us—we are ourselves interested in and fixated on mystery. I think we look at the world and we don’t find it explicable. It hasn’t been, and shouldn’t be, deconsecrated. The world is alive, and emanates mystery. What we’re trying to do with our music is reconnect people with that sense of mystery, that sense that there’s a depth and uncertainty to everything that we take for granted. This is especially crucial in the secular, materialist, capitalist world, where everything has been reduced to commodity and brand.

I think that sense of ‘sacredness’ is one of the things that attracted me to your music. At the time I discovered your albums, I was attending a very conservative ‘Bible college’ that approached the Bible from a rigid, literalist perspective—which over time started to feel somewhat antithetical to the very nature of religion. There’s something about that tendency toward literalism that I think is particular to the American interpretation of Christianity.

The literalism of both Christian fundamentalism and secular culture are flip sides of the same thing—our collective alienation from the idea of mystery. It’s the idea that, in some way or other, we want to be self-sufficient, we want to be in control, we want a rule book. We want to make the world explicable, and we want to put ourselves at the center of it. And I think we’ve lost that notion of the sacred; whether you’re at the secular end of the spectrum or the fundamentalist end of the spectrum, we have made the world mundane. We’ve impoverished the sense of reality to the point where the poetic, the mysterious, and the beautiful are all concepts that we’re increasingly detached from.

There’s a lovely quote from [Catholic writer] Thomas Merton [that comes to mind]. When he was teaching at Gethsemani, he was in charge of the ‘junior monks.’ And they thought, ‘Here’s this guy who’s been a poet, a campaigner for peace and civil rights, a countercultural icon—we’re going to get some really interesting readings, and we’re going to be subjected to some really interesting, contemporary ideas.’ And yet everything he gave them to read were the Gospels and the Church Fathers. And they got sick and tired of this, so a little delegation came to him and said, ‘Why are we reading this old stuff when there’s so much interesting new stuff happening in the world?’ And Merton said, ‘If you had to draw a pint of water from the Mississippi River, would you go to the delta or would you go to the source?’

For us, [Eastern] Orthodoxy is the source, and I think that’s why it appeals to us on a spiritual level, and I think it’s why we understand the deep intimacy between the Orthodox notion of beauty and the Orthodox notion of the sacred—because they both speak eloquently about how they see creation, and they see it in a way that’s radically different from the modern materialist consumerist worldview we have today.

What I like about your work is that it’s not necessarily specific to any one religion—you draw on multiple sources of truth. There’s an adaptation of a Sufi poem on your latest record.

I think we find that there is deep affinity—a depth—when all religious and spiritual traditions discover commonality. I think what’s happening today in the world, people are searching for connection and identity, and they’re finding it in ways that separate themselves from one another, and in ways that give rise to sectarian disputes. If anything, we’re trying to preach that the deeper you go, the closer you get to something that is fundamentally and irreducibly human.

A lot of those central tenets have been carried throughout your work. Another thing that has remained constant—in a more tangible sense—are the group’s core players. You’re surrounded by a rotating cast of musicians, but the heartbeat of the group has always been you, Leslie, and Paul.

And Paul is the common denominator. I was at school with Paul, and Paul lived across the road from Leslie. Les was a percussionist, and Paul and myself played in a really crap band. We were trying to merge punk, Captain Beefheart, The Velvet Underground, and every other kind of experimental music into one entity, and it was just incoherent. We gave up. We thought, ‘There’s no way we can express ourselves through music,’ so we started making films. But then we had to create some sort of means to show those films with live music, and so Les joined—initially as a musician, but then became integral to the whole thing. And I think we [gradually] discovered that if we wanted to express ourselves, it wasn’t through making films.

It’s become increasingly difficult for us to execute our vision [for live performance], so what we do now, primarily, is record. It’s incredibly difficult to find space to perform because there are too many of us [the group performs as a nine-piece—ed.], and because we don’t fit into a conventional performance space. The other thing which has become obvious to us is that there is a secular presumption that what we’re doing is suspect. A venue we know very well, when we asked about performing there, they said, ‘Yeah, but you’re a bit religious, aren’t you?’ From their point of view, they thought that would grate on their audience, or their self-image, or their brand—whatever. And that’s become a recurring theme. We haven’t crossed over into the levels of popularity that other so-called ‘neo-folk’ artists enjoy because I think there’s a sense that we’re not on that page—that we represent something that is still a little bit disreputable, and a little bit controversial, maybe.

Which is funny, because so many of those neo-folk bands openly draw on Pagan themes and traditions.

Oh, yeah, [apparently] that’s fine. And they do it either in a kind of ironic, post-modern way, or then there’s the more sinister end of the neo-folk spectrum, which is really a kind of quasi-fascism—which is something that worries us enormously. It worries us that we get lumped in with neo-folk artists who I regard as being almost Nazi apologists, or artists who flirt with dark, dangerous, fascistic ideas and motifs in a way that I think is shameful and irresponsible. There’s this idea that you can appreciate their art without buying into their ideology. To me, their art and their ideology are joined at the hip. Especially now, with what’s happened in your part of the world with Trump, and what’s happened over here with Brexit, there is something ugly on the rise. I’m reminded of that quote by W. B. Yeats [from his poem “The Second Coming”]: ‘The best lack all conviction while the worst are full of passionate intensity.’ It’s from this prophetic vision of the second coming, and you begin to feel a little bit apocalyptic when you see the way the world is moving at the moment.

Hearing you say this, I’m reminded of something you said in an interview, where you described your music as providing ‘restoration.’ I’d be curious to hear what you feel humanity to be restored from, and what it needs to be restored to.

It’s extremely difficult to not become overtly spiritual while talking about this, but I think humanity needs to be rescued from the delusion of self-sufficiency, and I think it needs to re-root itself in a sense of the sacred and the Divine. This comes back to the core of both Orthodoxy and Sufism, the idea that you only begin to realize your obligations to other people when you’ve plumbed the depths of your humanity until you reach a point of connectedness to what religious people call God. And I think that’s what we’re saying when we talk about ‘restoration.’ You’ve got to recover the authentic potential of humanity and stop living in this kind of distorted, subverted, tediously narrowed notion of humanity that is only leading us toward literal self-destruction.

Vinyl LP

We talked earlier about the fact that, initially, you had set out to become filmmakers. Film figures prominently into your work, especially those of Andrei Tarkovsky. What draws you to his films?

We just collectively fell in love with Tarkovsky’s work. We talk about our music as not being music, but almost almost like simulating the memory of music, or the residue of music. We saw our music as being a soundtrack to something. It was trying to delineate or describe something that was not visible or not yet audible. And when we saw Tarkovsky’s films, it was almost as if we saw the film we were trying to write the soundtrack to. It’s just beautifully transfigurative—the depth, the beauty, the mystery. All of his films, in a sense, are about that journey toward restoration, that journey back toward a sense of wholeness.

Another touchstone, obviously, is Luis Buñuel. The name of the band comes from That Obscure Object of Desire. That’s an interesting combination, to me, Tarkovsky and Buñuel, because one of them is very spiritual, and the other is a bit more interested in absurdity. I wouldn’t necessarily think of the two in the same space.

Well, what we liked about the surrealists was that, although they collapsed their radicalism into a Marxist vernacular, they were rebelling against the same reductionist view of humanity, the same reductionist view of reality, and the same reductionist view of the poetic potential of the everyday. I think Buñuel as a complex character. He lived his entire life both as a kind of atheist, and also as someone who was obsessively preoccupied with religious questions. But I think what attracted us to the name ‘The Revolutionary Army of the Infant Jesus’ was the fact that there was an ambiguity to it. There was this provocative sense of ‘proclaiming a mission.’ The name is more problematic now, I think, because the notion of religion and terrorism have become inextricably connected in a rather horrible way. But at the time we liked that juxtaposition, the idea that one could assert spirituality in a way that was radical, challenging, and uncompromising. To be honest, we recently had an internal conversation about whether or not the name had become a bit of a barrier, or a bit of an albatross, and whether we should say ‘this project is now terminated.’ But for the time being at least, we’re still in this vehicle.

One of the reasons we’re talking today is because your 1991 album Mirror was just reissued. Looking back on that record now, what about it stands out to you?

I don’t think any of us had listened to Mirror a great deal in the intervening decades, and so we were kind of surprised by how much we liked it, I think. I was remembering how it was a much more difficult album to record than either The Gift of Tears or Beauty Will Save the World. But listening back to it, it does sound quite fresh. It’s got a depth and subtlety to it that we didn’t necessarily appreciate in the immediate aftermath of recording it. It took so much out of us that I don’t think any of us really wanted to play it that much once it was finished!

Vinyl LP

And to close, given the fact that your music is so hard to categorize, I was genuinely curious to know: Who were some of the artists who first changed your idea of what music could be?

Some of the commonalities between all of the members of the band are quite obvious: The Velvet Underground, Scott Walker. I think we all, in different ways, were influenced by different kinds of sacred and liturgical music and by classical minimalist music—composers from Messiaen to Arvo Pärt. The reason why our music doesn’t sit within a specific genre is because we’re not ‘musicians.’ We’re trying to create soundtracks for something, and whatever that is, it pushes us. I don’t think we’d ever define ourselves as being musicians—I don’t think we’re good enough to be musicians! I’ve got proper respect for people who are musicians, and it normally requires a great deal of hard work and technical discipline, and these aren’t virtues that we necessarily distinguish ourselves in.

If you don’t think of yourselves as musicians, how do you think of yourselves?

I think we think of ourselves as confused individuals, stumbling around in the dark, trying to find some recognizable landmarks. Trying to find our way home.

—J. Edward Keyes