“This is the song about pickup trucks and liking girls that country music has been waiting for,” Karen Pittelman announced on stage this past January. Pittelman was performing with her band, Karen & the Sorrows, as part of the Queer Country Quarterly, a regular concert series that features a variety of queer-identifying country and roots musicians that she’s both organized and hosted at the Branded Saloon in Brooklyn since 2011.

Pittelman was introducing “Take Me For a Ride,” a song on her band’s forthcoming album that she wrote as her own take on “bro country,” the brand of oft-derided, commercial country that has taken hold of mainstream country music over the past five years.

“Right now, the critique of ‘bro country’ is that it’s the same old ‘girl in the pickup truck, with the painted-on jeans,’” Pittelman says during a recent interview in Brooklyn. “I agree with that critique. It’s boring to have the same song over and over again. But we can also ask more of a genre, rather than just throwing it away.”

In a musical style where heterosexuality is assumed, and where flirtation, sex, and romance is often filtered through a male perspective (to wit: there is currently just a single female solo artist among the 10 most popular country songs in America), Pittelman’s song offers a rare moment of splendid subversion: “Don’t care what those folks say / ’Cause I don’t even have one doubt / Wanna kiss that pretty mouth / And then keep on kissin’ south / You’re still the girl I dream about.”

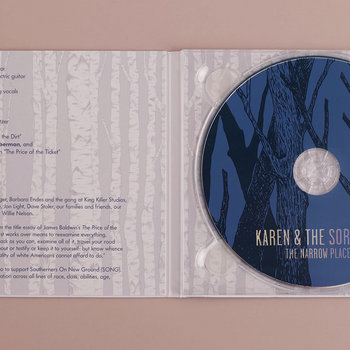

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Pittelman wrote those lyrics after stumbling upon a standup routine online from the Southern comedian Ali Clayton that bemoaned the lack of country songs about “eating a pussy in a pickup truck.”

“If country music can’t tell a story about a girl picking up a girl in a pickup truck, then it’s missing out on so many possibilities,” says Pittelman.

On her band’s second album, The Narrow Place, Pittelman is determined to depict that reality. Described by Pittelman as, “a weird mix of Jewish country songs and queer bro country songs,” The Narrow Place uses pedal steel-driven, rootsy songs that recall Harvest-era Neil Young to explore a variety of unorthodox subjects. The album’s title is a translation of mitzrayim, the Hebrew word for Egypt, and a decent portion of the new record is comprised of Talmudic tearjerkers about Passover. “Price of the Ticket” uses the story of Pittelman’s grandfather to explore ideas of, “immigration and whiteness and Jews becoming white,” while “I Was Just Your Fool” transplants King Lear’s fool into a honky-tonk setting. The album is being released on purple vinyl, a nod to pioneering early ’70s queer country band Lavender Country.

That the stories told on Karen & the Sorrows’ new album feel so radical is a reminder of just how limited the scope of vision and subject matter can be in modern, commercial country music. “An entire genre,” says Pittelman, “is missing out on sharing the perspective of this enormous part of its audience.”

The Queer Country Quarterly

Karen Pittelman founded the Queer Country Quarterly as a response to that lack of queer voices in country and roots music. Unlike mainstream country which, to its detractors, can feel homogeneous in sound, style, and substance, the Queer Country Quarterly’s definition of country music is loose and adaptable. It incorporates everything from straightforward folk to garage cowpunk to traditional bluegrass and rockabilly. On the night Pittelman debuted “Take Me For a Ride,” the QCQ’s three-act bill skewed toward punk and rockabilly—or, as Pittelman put it before the show, “Hard rockin’, guitar slingin’ tough femmes.”

More than 60 acts have played the Queer Country Quarterly, including several of the most exciting young voices in roots music, like Virginia bluegrass traditionalist Sam Gleaves, Tennessee gothic folk-blues singer Amythyst Kiah, and North Carolina indie folk trio Mount Moriah.

The origins of the Queer Country Quarterly date back to April 2011 when Pittelman decided she wanted to organize a show for her birthday. Both Pittelman and Elana Redfield, Pittelman’s partner and the founding guitarist of Karen & the Sorrows, were part of a small subset of musicians who had been playing for a few years in Brooklyn’s burgeoning alt-country/roots scene, but they never quite felt at home. Part of the disconnect, Pittelman says, was feeling out of place in the aggressively traditional, straight-laced world of Americana and alt-country.

“I think it’s hard to feel the urgency for something if you don’t need it yourself,” Pittelman says.”One of the best things about punk’s legacy is the idea that, ‘If you need something, go fucking make it.’”

Pittelman’s premise for her birthday show was simple: recruit some friends’ bands to play a queer-themed country night. She’d call it the Gay Ole Opry. When 350 people showed up on a weeknight to two-step and listen to old-time country music, Pittelman was taken aback.

“People came up to me after the show crying, saying things like, ‘I grew up in the Midwest,’ or ‘I grew up in the South, and I never felt like I could be in places like this with my partner, dancing to this music,’” she says. “I remember thinking that I had to do something with this. I had no choice.”

Soon after, Pittelman reached out to Gerard Kouwenhoven, whose band Dolly Trolly shared rehearsal space with Karen & the Sorrows, and who Pittelman had collaborated with over the years. When Pittelman found out that Kouwenhoven was opening a new bar called Branded Saloon, she asked if she could turn her one-off Gay Ole Opry party into a regular show. “Instantly, I set aside one Saturday a month for her, and the Queer Country movement was born,” says Kouwenhoven.

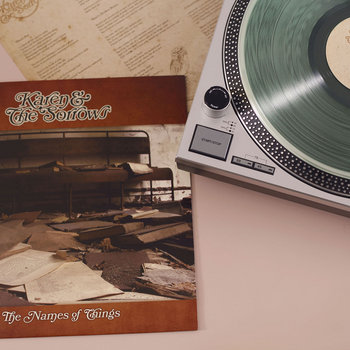

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

In the six years that followed, Pittelman eventually became a central figure in New York’s queer country music community, organizing regular shows for the Queer Country Monthly, which eventually became the Queer Country Quarterly. Occasionally, she puts together larger events, like Another Country, a festival taking place over 4th of July weekend that brings together “queer, trans, and/or POC musicians” to communally question the definition of country music.

Pittelman has also become one of the most important focal points for the scene nationwide, expanding the community’s network by bringing artists from around the country to play assorted Gay Ole Opry gatherings and the regular Queer Country Quarterly shows in Brooklyn.

“It’s surprising how many emails and calls I get from people who want to play the Queer Country Quarterly,” says Kouwenhoven (who, in addition to owning the Saloon, also mans the soundboard at the QCQ and sings harmony for Karen & the Sorrows). “The fact is that there are a ton of gay people who create and enjoy country and folk music.”

“There’s always been queer people making country music,” says Pittelman. “We just started labeling it as such. Building this network has been really exciting because you see how many people all around the country are having the same thoughts.”

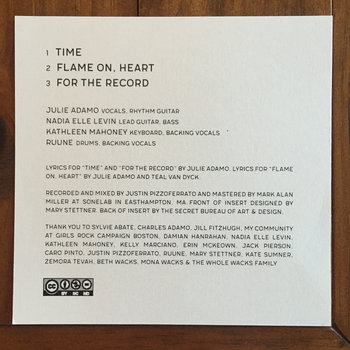

“Karen’s done such great work, as far as making a locus of community around country-related styles of music and queer folks,” says Julie Adamo, who fronts the roots-punk outfit Julie Cira. “I’m so appreciative to be a part of it.”

Julie Cira’s music blends the melodicism of Lucinda Williams with the punk energy of Lydia Loveless, but in Western Massachusetts where the band is based, they don’t quite fit either into the traditional folk scene or the DIY punk scene. Their sound is more at home in the former, but their ethos and sense of community is much more closely aligned with the latter.

Compact Disc (CD)

When they performed at the Queer Country Quarterly this past February, Adamo expressed gratitude for the QCQ community during her band’s ferocious set. “This is a dream come true,” she said. Then, she played a new song called “Drown Out the Voices That Tell You You’re Nothing,” which seemed to encapsulate the precious space that the QCQ provides: “When you feel you’re the only one,” she sang, “know you’re one of many.”

Appalachian folk singer Sam Gleaves offers similar praise. “Karen’s done a really special thing organizing this series,” says Gleaves, who first met Pittelman when he was opening for Karen & the Sorrows during their southeastern 2016 tour.

“There aren’t very many places where I can celebrate my identity as an Appalachian musician and as a queer man, and this is a space to do both of those things. It’s not so much about me as it is about the community and the feeling of knowing that there are other people who are on the road using country music to sing about their identity and our place in the world.”

In his own music, Gleaves excavates untold Appalachian stories and forges new ties across class and gender lines. On Sam Gleaves & Tyler Hughes, his new album with his musical partner, Gleaves recontextualizes traditional music during moments like “When We Love,” an Appalachian-tinged ballad that turns Donald Trump’s campaign slogan into a prayer for love and compassion.

“When people hear these old sounds, they think of their community, and when they hear the contemporary, political lyrics, they think, ‘What will we do?’” says Gleaves. “I love that.”

On the title track to his 2015 breakthrough Ain’t We Brothers, Gleaves tells the story of a gay coal miner seeking solidarity with his fellow workers. Pittelman can still recall the first time she heard Gleaves perform the song.

“I felt so connected to all the people for whom that’s their song, who never got to have a song before. That’s the whole point of this, to make it possible for people to tell the truth about their lives because we all need songs. That’s part of how we survive this shitty world. When Sam sung ‘Ain’t We Brothers,’ I felt the presence of everybody who, for all these years, have been waiting for that song, and of people in my own life who died for the lack of that song,” she says, before arriving at perhaps the best possible explanation for the precious importance of the Queer Country Quarterly: “It’s a serious thing when you don’t get to see your own life reflected back to you by the art that is meaningful to you.”

—Jonathan Bernstein