If the American empire is crumbling, Connecticut producer Gaffe of a Lifetime has seen it coming for a while. His debut The Errors: A Kingdom of Loss was a dark, progressive house project with titles that hinted at socio-political anxiety. The March release predated Donald Trump’s ascension to the White House. The Moroder-esque organs of “Plugged Forth, The Worst Has Yet To Come” now feel prophetic, and Gaffe of a Lifetime’s dark techno does not offer utopian futures. The writing on the wall for Gaffe looks an awful lot like an elegy. The music still offers blissed out, arpeggiated pandemonium, like on “21st Century Collapse,” but it’s bookended by a funereal closer called “And This Is Where You Have Died.” None of it has been incidental. Gaffe of a Lifetime—aka producer Alexandre Louis Petion—transmits his belief that dance music can be more than escapism.

Before he started recording as Gaffe, Petion taught himself to translate emotion into electronic music. He says intuitively he foraged for vocal samples and obscure sounds that encapsulated his feelings. As it grew into Gaffe of a Lifetime, the purpose was to hack his consciousness into the framework. In Petion’s music, glitches are used to elicit emotional feedback. With his new release, Mansa, and the Far End of the Death Spectrum, Petion has created a dissenters’ soundtrack, reminding us to question our reality—or worse, our simulation.

Cassette

Why did you include the definition of glitch on The Errors Bandcamp page?

The two words I’m always fixated on [are] error and loss. They signify a sort of shared idea of ‘glitch.’ Loss can be associated with death, or something being taken. It can also be a data loss, or something corrupted—your hard drive being erased. When a glitch happens, you feel set back by it. ‘Glitch’ is like putting you in a constant state of disarray. I feel like that’s what I want to do with my music. It’s an intangible anxiety that you can’t remove.

How is glitch present in your music?

Most people associate glitch with its technological definition. Glitch itself is really not an art style, it’s just a mechanical error inside the language of the image. You’ve messed up the code inside the picture. The intention is to deform the art. I wanted to use that art style with my music. With glitching, it goes wrong. It’s not supposed to be. I intentionally messed up the art cover. You can see a figure misplaced. There’s something wrong with it. For The Errors and most of my work, glitch is very important. It’s not the genre of glitch music. It’s a feeling.

Does your idea of glitch pertain to simulation theory?

I’m always trying to push anxiety onto the listener—that sickening feeling of something not being right. A simulation is definitely part of the idea behind Gaffe of a Lifetime. It’s very much an Internet sensibility I’m trying to connect with, but also disconnect at the same time. I feel like with the Internet and technological stimulation, it’s rooted in the music and I’m trying to take it out and show you the roots themselves.

Are you intentional in not allowing Gaffe to be compartmentalized in a singular genre?

I don’t think people are concerned about social consciousness or intentional messages to be heard or produced in a dance music track. No one is expecting anything other than a four-on-the-floor beat. That’s why I feel like I’m not a part of a genre, even though I make music that sounds similar to it. I’ve got a different philosophy [in comparison] to what other producers are doing. I feel like producers who are just making people dance, I feel like that’s what they truly want to be doing—providing a very pure, organic atmosphere of joy. I’m not necessarily part of that. I want to make enjoyable, danceable music, of course. The goal for me is trying to reach something else, trying to transcend something in dance music. I wanted to make it vague as an aesthetic. I’ve also wanted to be blatant and obvious in what I’m trying to portray. I’m on this schizophrenic pendulum of making [the project] esoteric and undefined, but also very descriptive and informative.

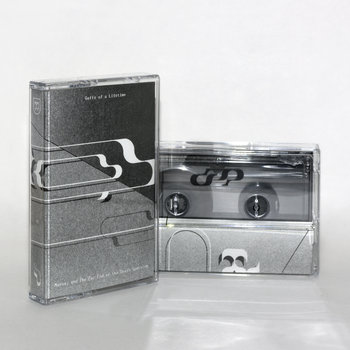

Cassette

Is communicating the intent of Gaffe without being obvious a struggle for you?

I’m still trying to make it really effective. Even with the poems, it’s still not enough for me personally to be effectively translated to people. The song titles are the most explanatory. If you try to use your imagination, there’s something to the song titles you can infer from. To me, it feels like electronic dance music is supposed to be visceral and attuned to feelings instead of having this declaration of process or language. I think that’s what I noticed before I even started Gaffe. From the very beginning, I knew it was going to be challenge. I was looking forward to that challenge.

What role does the idea of imperialism plays in this release? It seems to have an ongoing presence in your work, but this time it’s with the presence of the Mansa, an African imperial figure, which is contextually different than the American one in the My Fellow Americans EP.

Mansa is the Mandinka term for king or ruler, a term I specifically chose for its African subtext of power and nobility. As for this release, it’s more of an underlying role more than anything. My Fellow Americans EP is probably more of an obvious admission of this role and I feel a little bit of the stuff on this tape is still reeling from My Fellow Americans. Maybe the idea you’re picking up is the image of this sort of structure of power that I keep embedding and reintroducing in my work that sort of gives off that presence you’re feeling. The other line “Far End of the Death Spectrum,” is yet another reference towards death, dying, and its literal tangibility. These two separate texts claused by a comma; simply juxtapose one another and stir a feeling, an idea, an image. One, of nobility and powerful rule, and the other, simply an inescapable consequence of biology.

Is Gaffe of a Lifetime you uploading your consciousness?

It’s sort of a musical singularity, I guess. There’s a temporality thing I feel. I feel like I can’t just upload anything. I have to upload everything that’s a part of me and part of my aesthetic and put that into the music. I do feel that way, that it’s part of my consciousness.

That feels attached to your desire to communicate beyond providing joy.

The entirety of Gaffe Season 1 is a message. When I’m making the tracks I’m really uploading my consciousness in that moment. When I’ve completed the tracks I feel removed from it. Once it’s finished, the zone I was in—the digital workspace—the message dies down. It’s further away. So, if I feel a certain way while making a specific song, I feel like it’s forever mummified in the song. When I feel like I’ve completed it, I’m giving those mummifications away.

—Blake Gillespie