The Atlantic slave trade didn’t just result in the colonization of the African continent—it also resulted in continuous efforts to colonize the minds, identities, and consciousness of the African Diaspora. In Trinidad, as in many other colonies, colonial authorities implemented different strategies in an attempt to distance enslaved individuals from their African roots, from forced conversion to Christianity to policies restricting the use of African languages, separation of communities, and prohibitions on traditional drumming and dancing.

But a quick look at Trinidad’s music today testifies to the vitality of these traditions and the resilience of the diaspora in the face of colonialism’s destructive force. Rooted in West African rhythms, calypso emerged here as a way for enslaved people to communicate, mock their masters, and maintain a sense of identity.

Vinyl LP

After the Abolition of chattel slavery in 1838 (Trinidad was the first British slave society to fully end slavery), hundreds of Mandingo, Igbo, Krumen, and especially Yoruba people who’d been liberated from foreign slave ships began settling in Laventille, a collection of communities nestled among the hills in East Port of Spain. This area became a hub of cultural resistance, and many of Trinidad’s now celebrated traditions, from calypso to carnival and even the steelpan drum, can be traced back to Laventille.

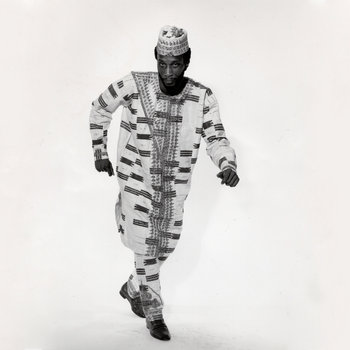

It’s here, in this deeply political and culturally vibrant place, that Oluko Imo was born in 1951. The singer and multi-instrumentalist would go on to become a beacon of cultural resistance, a deeply spiritual and socially committed artist whose music would serve as a profound act of defiance against the erasure of the diaspora’s “Africanness.” Blending calypso heritage with the Afrobeat and jazz of Nigeria, Imo explored and reclaimed the Trinidad-Yoruba connection, and would go on to play regularly with none other than Fela Kuti, with whom he developed a close relationship.

Born into a musical family, Imo grew up listening to the likes of Bert Bailey and his Jets, and eventually joined the Blue Veils, a combo band (a small ensemble that plays a mix of genres, including calypso, soca, and pop) who performed covers of North and Latin American songs, first as a guitarist before switching to bass and vocals. But before his musical career could truly take off, revolution swept Trinidad.

On February 26, 1970, thousands of trade unionists and students took to the streets with their clenched fists held high, crying slogans of “Black Power.” They were protesting the arrest of a group of Caribbean students who had been detained following a sit-in protest against racial discrimination in Montréal, Canada, the previous year. What began as a peaceful demonstration transformed into a more militant movement following the police’s violent crackdown.

Though it was these events that sparked the Black Power Revolution, the deep dissatisfaction with neo-colonial economic and social structures left over from the days of British imperialism had paved the way. Inspired by the words of Trinidad-born, U.S.-based civil rights leader Kwame Ture, Afro and Indo-Trinidadians united to protest the inequalities which kept them subjugated.

A State of Emergency was declared on April 21, 1970, and several of Imo’s friends and classmates were arrested. The violent repression and strict curfew were the last nails in the coffin of Port of Spain’s previously vibrant nightlife. But what could have been the end of Imo’s musical career instead served as the catalyst for the deeply political, socially conscious music he would go on to make for the rest of his life.

“He was always very strong-minded when it came to anything to do with Black Rights and Black Movements,” recalls Grace Imo, his widow. “He always used [his music] for the Black Rights Movement.” It was during this time that Imo also started further exploring the African roots of the music he’d grown up with.

According to Imo’s bio, written by Trinidad-born writer and cultural worker Attillah Springer, ahead of Soundways’ remastering and release of four of his best-known records, Imo and others were particularly inspired by an elder named Baba Imo, who led the local chapter of Marcus Garvey’s UNIA. “Baba Imo was teaching us Yoruba language and drumming. It was under his guidance that we were given new African names. It was in Baba Imo’s yard that we spent time with Bertie Marshall and Rudolph Charles, who were seriously innovating with the steelpan,” writes Springer, quoting the words of Blue Veils guitarist Andre Labeijoba Wallace.

Shortly after the Blue Veils dissolved in 1971, Black Truth Rhythm Band was born, with Imo contributing lead vocal, bass, kalimba, conga, flute, and percussion, and Andre Labeijoba joining him on guitar. This time, their sound was much closer to calypso, which was proving to be a powerful agency of Black Power and Black consciousness. They also looked to Africa for inspiration, going as far as giving themselves African names and dressing in African clothes.

“He even changed his name from John Andrews to Oluko Imo. Anyone who heard that would think he was from Nigeria, but he had no ties to Nigeria at all,” recalls Grace Imo. “He believed in spirituality, he believed in tradition, and he believed in culture. So when it came to African traditions, he was very interested in the spirituality and rituals of, for example, the Yorubas and Igbos, and he had full respect for them. He was a very peaceful man and very open-minded with everything.”

Inspired by the Black Power movement and by Orisha, the spiritual tradition of Yoruba people, along with his own Afro-Christian Spiritual Baptist faith, Imo grew ever more convinced that Black Truth should be committed to making socially conscious music. Trinidadian audiences were not so sure. After a rocky first few years, the band’s steadfastness paid off when they won a local competition in 1973, resulting in a cash prize and a recording contract. Black Truth Rhythm Band soon became the biggest band in Port of Spain. In her bio for Soundways, Springer quotes the late Brother Resistance, revered as the Father of rapso music, reflecting on the impact Black Truth had on him: “It was music that showed me that I could bring out my African self in my music.”

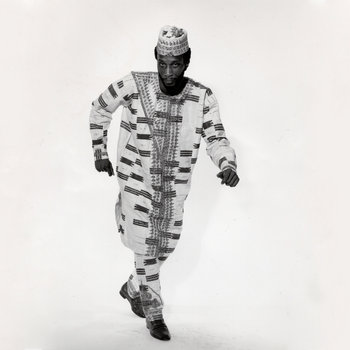

Vinyl LP

“Aspire,” Black Truth’s first single, was released in 1974, its B-side track “Imo” reached number three on the Caribbean Hit Parade. Ifetayo was released two years later and was an instant hit. The Soundway reissue gives new life to the record’s deep, rich grooves, and highlights the band’s Afro-Trinidadian style right from the start with the colorful medley of mbiras, flutes, and hypnotic Yoruba drumming on opener “Kilimanjaro.”

“We would like for you to join us on a journey to Mount Kilimanjaro/ We will be traveling into higher highs and deeper depths,” Imo intones in his smooth, deep voice, as the track escalates to the sound of cries and ululations, capturing the transcendental energy of spiritual gatherings and rituals. On eight-minute slow-burner “Umbala,” a mellow Hammond organ, light steel drums, and West African percussion coalesce into a laid-back, dreamy groove, while Imo’s soothing voice floats above. The title track is a funky, upbeat cut that blends catchy guitar riffs with polyrhythmic percussion and flourishes of flute and thumb piano, while “Save D Musician” adds a stronger Trinidadian flavor and a touch of melancholy.

Yoruba for “love is enough for joy,” Ifetayo would be Black Truth’s only album, but it was only the beginning for Imo’s journey into African music and culture. Though the album had been a success, and the band even opened for Peter Tosh in Port of Spain in 1978, they dissolved before another record ever materialized. Imo left Trinidad for Venezuela, where he reconnected with musician and friend Franklin George, a member of armed Marxist revolutionary group The National Union of Freedom Fighters (NUFF) who’d been forced to flee Trinidad after many of his companions were killed by the police in the early ‘70s. However, it was an encounter with another musician that would alter Imo’s life forever.

Imo met Fela Anikulapo Kuti when he left Caracas for New York, and the two immediately bonded. “They were more than brothers. He loved Fela’s ideas and music, and how he focused on Black nations and talked about the corruption of the leaders and all the bad things they were doing to citizens. He especially liked the idea that Black nations should start managing their own business, instead of looking to the White Man for help” says Grace Imo, who is originally from Ghana and now lives in New York.

Imo began traveling regularly to Lagos, and eventually moved there, working both as road manager and bassist for Fela’s Egypt 80 band. Here he endeavored to learn everything he could about his African roots: “Oluko was very exceptional, he wanted a link to Africa and to study who his ancestors were” says Duro Ikujenyo, who played keys for Fela Kuti in the Egypt 80 band, in an interview with Soundway. “He met the Young African Pioneers [the direct-action political movement Fela was involved with] in Fela’s house, not just anybody. People who were reading Black Man of The Nile, Religion of the Yorubas and so on, so that gave him a bit of inspiration to say he wants to be a part of Africa.”

Imo’s 1988 song “Oduduwa” directly stems from his interest in Yoruba spirituality. Taking its name from the founder of the Ife Empire, who is also seen as a divine Orisha (deity) in Yoruba culture, the track is a plea to the Black diaspora to stay connected to their African roots, and to Black people to stay united in the face of divisive forces such as poverty and oppression. Both Fela and Femi Kuti appear on the flip-side track “Were Oju Le (The Eyes Are Getting Red),” a shining example of Oluko’s laidback transatlantic Afrobeat, with its Caribbean-inflected guitar, characteristically Nigerian horns and keys (played by Duro Ikujenyo) providing a solid starting point for Fela Kuti’s brilliant sax solo. The song is a biting commentary on the dire economic state of Nigeria at the time, and encouragement to the people to fight against the system. “Were Oju Le is like a street language that means that you are repulsive to the conditions of the system, and […] that people must just fight against such situations. Everything is difficult, there is no food, there is no house. He was the voice of the masses,” says Ikujenyo.

Grace Imo recalls her late husband’s deep commitment to social justice: “He was very into politics, but not for his own interest. He was actually against people who wanted power all for themselves. He didn’t want to become a politician or pursue power, but he always had strong opinions on what was right and what was wrong. It was more of an awakening, to wake people up so they could make the right decisions.”

In 1995 he released Glory of Om, which was written in Lagos and sleekly produced in New York. By this point, the Afrobeat rhythms which he’d absorbed during his time in Lagos playing with Egypt 80 were an intrinsic part of his music, but his voice, melodies, and delivery are unmistakably Caribbean. The title track is catchy and uplifting, propelled by Imo’s sun-soaked, calypso style call-and-response vocals, backed by a radiant burst of percussion, keys, saxophone, and guitar. All across the album, like on the lovely, soaring “Seeking For The Right,” underpinned by Fela-style Afrobeat rhythms, Imo spreads messages of unity and positivity, highlighting the injustice of enduring post-colonial structures across the world.

After Fela died in 1997, Imo traveled to other places in West Africa, including Accra, Ghana, where he met his wife Grace in 1998. They married a year later, and although they moved to New York in 2000 they returned often to Ghana, where he would seek out local musicians to play with. “He got very close to [British-Ghanaian-Caribbean rock band] Osibisa, so he would rehearse and play with them if they had a show,” recalls Grace.

In 2002 he returned to Lagos to collaborate with Fela’s son Seun, who in the meantime had taken his father’s place as Egypt 80’s bandleader. The result of this collaboration was Anoda Sistem, Imo’s last album and the culmination of his efforts to reconnect the music of Trinidad with its African roots. This “mixed heritage” is immediately obvious a few seconds into “Devine Mama,” the album’s opening track, with its punchy horn section and rumbling Afrobeat percussion subtly intertwined with those infectious hip-swaying Caribbean rhythms. Seun Kuti lends his vocals to the Afrobeat cut “City of Gate,” in which he sheds light on some of the issues affecting Lagos. As he had always done, on Anoda Sistem Imo addresses themes of inequality and global struggles for freedom and rights.

When Imo passed away in 2007, he was relatively unknown in his country of birth. “Even though he is gone, the message he put into all his songs and writing is still meaningful” reflects Grace. “His music, like Fela’s, is a weapon. It might sit in your mind, until you see something that rings a bell and think ‘Oh! That’s what that musician was talking about.’” Safe to say that, all these years later, Imo’s message remains as crucial as ever.