At the start of their concert in Portland, Oregon, on October 24th, 2019, the three members of Cinder Well, without announcement, began singing an old Baptist hymn a cappella, setting the tone for their performance alongside Anna Vo. The set that followed was a mixe of Cinder Well’s own songs—eclectic folk music that tells emotional stories of home and memory—with songs drawn from West Irish villages and the Jewish diaspora. The minimalist production on the group’s most recent record, 2018’s The Unconscious Echo, gives their music subtle, trance-inducing qualities, and the stripped-down approach serves them well. “Strangely, when I try to remember where and when I wrote a particular song, I often find that I have no memory of it,” says Amelia Baker, who plays steel guitar, sings, and does much of the group’s songwriting. “I have found that the best songs come out almost all at once. When I find myself meddling, overthinking, theorizing with a piece of music, it’s usually not going to make it out of the mill.”

Cinder Well are part of a small group of musicians emerging from the metal, post-metal, and industrial scenes to spearhead a kind of new folk revival. Formed, as most micro-scenes are, from informal networks of intensive collaboration—playing shows together and appearing on the same labels—it’s a movement led by women and gender non-conforming artists who see what they do as inherently political. Brenna Sahatjian from Aradia and Tay Lore of Byssus have played together in two side projects: the short-lived crust band Even Wind Turbines Kill Birds and the “anarcha-herbalist folk quintet” project Slow Teeth; Cinder Well developed as Baker was touring with her earlier band, The Gembrokers, featuring Burl Wood from Byssus.

The folk revival of the 1960’s and ’70s went hand-in-hand with the protest movements of the New Left. Though the image that usually comes to mind is that of a white folkie with a guitar—Bob Dylan or Joan Baez—some of the most powerful protest music at the time was R&B, soul, and funk. There were indigenous artists like Buffy Sainte Marie—whose “Universal Soldier” remains sadly relevant—and gospel superstar Mahalia Jackson, who performed at the March on Washington. All around the world, artists playing traditional music and its offshoots—whether it’s labeled as “folk” or not—help to preserve regional folkways historically erased by settler cultures, acting as both reservoirs of oral history and vehicles for storytelling.

“We have a lack of meaningful connection to traditions in general—in the dominant culture at least,” says Brenna Sahatjian, of the neofolk band Aradia. “So folk music, and gathering around music, feels really powerful for those of us craving connection. If it feels connected to the past, it’s even more powerful. Anything that brings us together can lend to the political work we are doing.”

“[Folk] literally means music of the people; it obviously had a rich origin in protest and resistance,” says Anna Vo, a non-binary artist of Vietnamese descent who has tried to reflect in their music the complicated hybridity of indigenous folk traditions in a world mired by American cultural imperialism. A prolific artist, Vo has released almost a dozen albums to date. “I am not a white person, so I don’t have the same connection to Irish, Celtic, Scottish, and Gaelic traditions of folk,” Vo says. “The music I reference in my project is specifically [modeled after] pre-war Vietnamese folk music, that was completely influenced by the U.S. military bringing in ‘60s rock n’ roll. So the questions around diaspora and bleeding influences that happen because of imperialism and immigration get a little more complicated for me.”

Vo runs the label An Out Recordings, which is home to anti-fascist metal projects like Ragana and Thou. With their solo project, they are stepping out of that world, and bringing their entire musical history with them.

Bound by sonics, relationships, and ethos, the artists in this growing scene also share a need to support one another, as their strong leftist stances can occasionally get them shunned by venues and headliners. “I think there have always been political folk acts out there looking to play shows together,” says Sahatjian. “What might be newer is the less blatant ‘protest music’ style and the more atmospheric, aesthetically focused, and genre-blending folk music that coalesces around radical politics. There is a community, but we are spread pretty thin.”

“I think it’s as a result of [the early folk movements] that we are now able to form a group that is influenced by traditional forms of music, yet challenges the old beliefs attached to it, both politically and musically,” says Burl Wood of Byssus. “I see Byssus as a group who not only speak out against colonization, imperialism, patriarchy, and fascism, but who challenge themselves to unpack and un-do our cultural indoctrination on a sonic level. We attempt to defy the laws of music theory, which itself is colonial in nature. What our ears perceive as sounding ‘good’ is entirely dictated by what we have previously heard in our culture. So, the intentional creation of what we call ‘dissonance’ is actually an act of dissidence,” says Wood’s bandmate Wesley Somers.

“It’s important to be an anti-fascist band, because it’s important to be anti-fascist—and for that to be 100% clear,” says Baker. This is particularly true as bands like Byssus and Cinder Well are sometimes erroneously grouped together with neofolk acts popular with the far right, like Sol Invictus and Death in June. “Music creates vulnerable spaces for both musicians and listeners,” she adds. “All I can ever hope to do with my music is to provide an environment where people can safely feel all the things they need to feel, and have a moment of reflection from the world we live in. Safely, without question.”

The cross-pollination within the relatively small scene between members of different projects have blurred all boundaries between them. Below, we explore these projects in more depth.

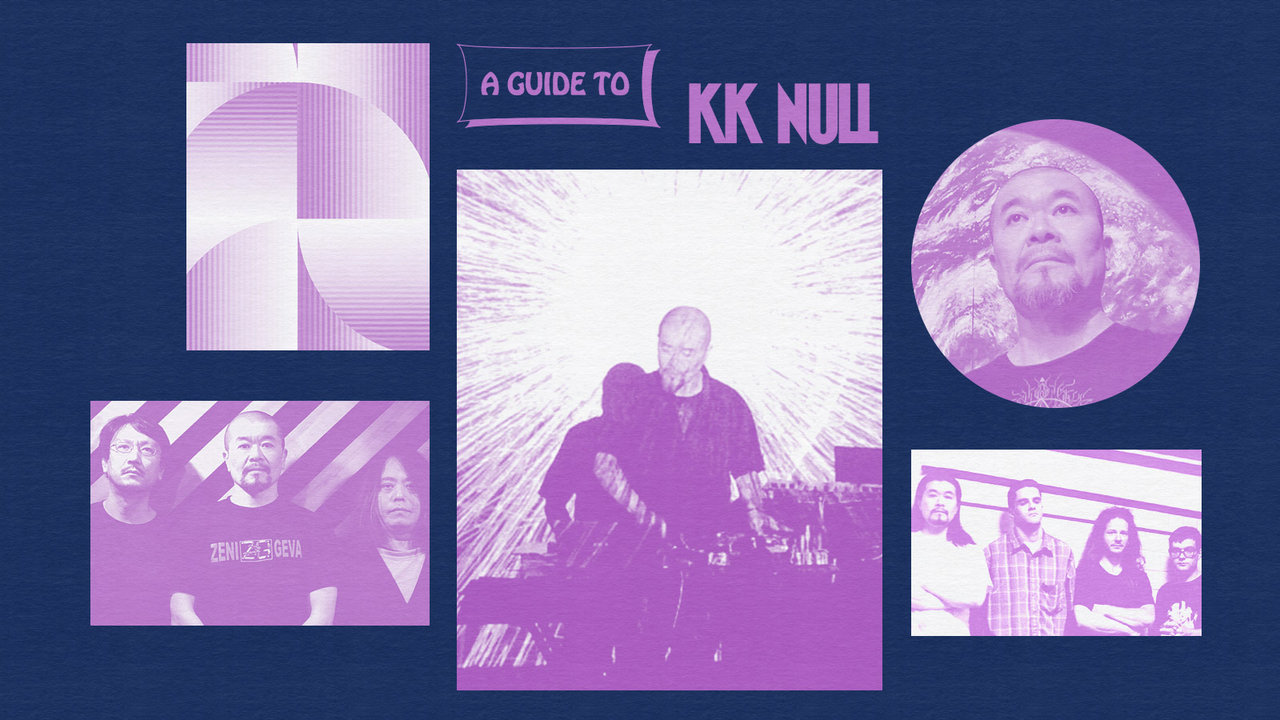

Anna Vo

Vo’s work draws on the folk sounds of the Vietnamese diasporic culture, which they meld with the hand-plucking of their 12-string and field recordings from nature—everything from volcanoes to the ocean. Their concept albums draw on their multi-media artwork, and their chameleonic ability to play multiple styles on multiple instruments (and even build their own). They are also a maestro of collaboration, jumping into projects with members of Aradia and Cinder Well. Vo just released a new two-track titled I call upon the dead to rise; the opening track “We Take on Water” draws from the intergenerational trauma of their family’s refugee story.

Aradia

Aradia’s distinct sound exists at the broad intersection of orchestral chamber music, metal, and anarcho-punk. Their political affiliations are right up front, too, with samples of revolutionaries like Audre Lorde and Ursula Le Guin—not to mention the prominence of their refashioned anti-Nazi “Iron Front” logo. Opening track “Omid,” on Aradia’s eponymous 2018 album, begins with a quote about the seeming inescapability of our current world, which is broken by a wall of sound, and lyrics that set the album’s confrontational tone: “Tear down these walls and build anew/ Our hope it arms us threw & threw [sic].” Two instrumental tracks follow, “Resignation” and “Revelry,” which are pressing, urgent songs that use layered instrumentation to beautiful effect—though there’s still plenty of dissonance and dramatics.

Byssus

A two-piece from Santa Cruz characterized by a dreamlike layering of vocals and a heavy-handed accordion, Byssus take a minimalist approach to folk. Their self-titled debut EP rests heavily on the resonator guitar, the sound of Appalachian hill music, and quiet mournful refrains—such as on the track “Osprey,” on which choral singing and instrumentation are layered to create an overpowering emotional outburst.

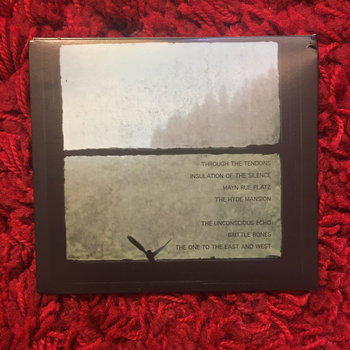

Cinder Well

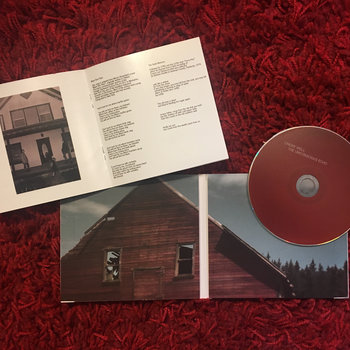

Compact Disc (CD), Vinyl LP, Cassette

Centered (mostly) on two violins and a steel guitar, the music of Cinder Well combines the various regional influences the group comes across during their collaborations with international artists—which they then re-contextualize for a modern audience. This makes their live performances something of an exploration, a mix of original compositions with re-imagined traditional music, always demonstrating a great deal of care and reverence for where the latter music comes from. The Unconscious Echo is an album of original compositions, drawn from Amelia Baker’s own life and travels. On the track “Insulation of Silence,” Baker ruminates on the power of a home—and its dissolution in the wake of sweeping gentrification.

The spontaneity of their live performances, and the deep well of history that guides them, is best heard on Live in the Emanuel Vigeland Mausoleum. Performed inside of a tomb in Oslo, Norway, designed by artist Emanuel Vigeland—the arching ceilings are painted with images of love, sex, and death. Cinder Well played this set in front of an intimate audience of 30, lit by candles. True to their social commitments, all the proceeds from that recording are going to the Water Protector Legal Collective, which supports indigenous activists fighting against climate collapse.