Two towering speaker stacks flank the Shieling World Stage at the Scottish roots festival, Knockengorroch—an unexpected visual for the folk band who have arrived onstage, armed with fiddle, guitar, and flute. The fiddler launches into Scottish folk’s characteristic birl, the flourishes from cymbals and flutes adding a spectral sheen. But just when you expect the slow build to descend into an old-fashioned hurly-burly, the tune takes a left turn, dropping into the plodding, dreamlike rhythms of dub.

These notes form the introduction to “Blue Dream” by An Dannsa Dub, one of the newest additions to Scotland’s dynamic Celtic fusion scene. Yoking the sounds of folk with contemporary genres like rock, funk, and electronica, Celtic fusion imbues ancient music traditions—sometimes hundreds of years old—with a fresh, modern sound.

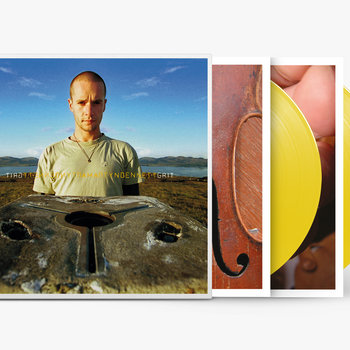

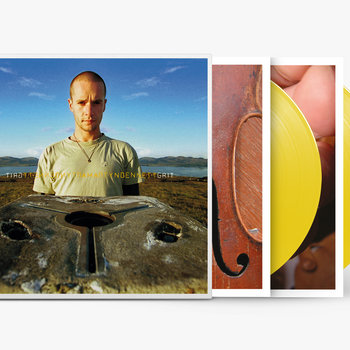

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

It sounds like it shouldn’t work. Bagpipes are a divisive instrument at the best of times, and the prototypical Celtic ballad makes an unusual match for electronic music’s driving beats. But An Dannsa Dub’s founders—Euan McLaughlin, a multi-instrumentalist who’s been playing at ceilidhs since he was 12 years old, and Tom Spirals, a reggae MC and collaborator of the Glaswegian sound system Mungo’s Hi Fi—insist that folk and digital dub make a more natural fit than you might expect. “The scales they use are pretty similar,” Spirals says, “a lot of pentatonics and simple repetitive riffs. The dotted rhythm as well—a little skippy hi-hat.”

“The reggae bassline sounds almost like little bits of Scottish tunes,” adds McLaughlin. “There’s a similarity in there.” Allan MacDonald of Niteworks, a band who blend bagpipes and Gaelic vocals with house and techno, agrees. “Musically the two are very close,” he says. “By and large, house or techno are 4/4, and the majority of stuff that you want to learn when you’re young are reels—which are also in 4/4.”

Niteworks started out as a group of four school friends playing trad instruments on the Isle of Skye before becoming immersed in the sample-based sounds of the label Mo’ Wax and its breakout star DJ Shadow. “One weekend we would be playing traditional stuff, and the next we would be DJing at house parties,” MacDonald remembers. “To us it didn’t seem like such a leap to go from playing trad stuff to buying synthesizers and trying to mix the two together. A large part of that was people like Martyn Bennett.”

Speak to any artist at the electronic end of the Celtic fusion spectrum, and Martyn Bennett’s name is almost certain to crop up. Known in the 1990s as the “techno piper,” he cut a striking image as the dreadlocked producer brandishing bagpipes. He wasn’t the first to combine Scottish trad with dance music—Shooglenifty had already crafted a sound they termed “acid croft”—but he breathed a new kind of artistry and countercultural thwack into the nascent scene. As British dance music evolved and splintered off from acid house into hardcore, jungle, and trance, Bennett weaved each into the Caledonian traditions in which he had trained. When he shared his recordings with the poet and academic Hamish Henderson, Henderson famously declared, “What brave new music.” “It was so ahead of its time,” says MacDonald. “He managed to nail it before anyone else.”

“The natural environment of folk music is informal; down the pub, right? And basically, they just don’t stop playing,” says Calum Cummins, the producer in Edinburgh-based band Yoko Pwno. “A lot of the reason that dance music works is because it’s hypnotic and repetitive and has a lot of space in it, so that’s a challenge. But Martyn Bennett’s work, particularly Grit, works really well because it’s based around a bunch of vocal samples. He was effectively remixing this old music.”

Compact Disc (CD)

Though Bennett grew up immersed in Scottish heritage (his mother is the folklorist Margaret Bennett), and went on to study piano and violin at Glasgow’s Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama, he was equally excited by the dance music then taking hold in Scotland’s cities. In the early ‘90s, he could be found busking with his pipes and a backing track emitted from a ghetto blaster on Sauchiehall Street, or raving at Edinburgh and Glasgow techno nights like Sativa and Slam. Beyond the hybrid sound he managed to conjure, he brought to life the transportive moments he found on the dance floor, both in Trad and club spaces. “Folk music has that sense of euphoria and high energy,” says Cummins. “It’s got a vibe, and dance music is about capturing that vibe, sticking a beat behind it, and then just letting that happen for an inordinate amount of time until the bar shuts.”

“We were trying to figure out how close an ancient Celtic festival would be to a modern-day rave,” says Spirals. “What are the parallels? I think there’s got to be loads—people essentially listening to really repetitive music and managing to access a different part of their brains.” It’s hard to ignore the subversive elements that underpin each genre, too. The UK’s Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, which in 1994 banned public gatherings with music characterized by “repetitive beats,” finds echoes in the Highland Clearances, when traditional instruments like bagpipes, tartan wear, and the Gaelic language were outlawed. The preservation of Scottish folk culture, for a time, was the very definition of “underground.” “Puirt à beul is a type of Gaelic music that came around,” says McLaughlin. “That was rebellion, them going: ‘Right, we’ll just make the music with our mouths,’ and then they all gathered in secret and had a dance. It’s the same as setting up a rig in the woods.”

What Bennett achieved was folk’s return to that countercultural realm, shedding its reputation for rigidity that it had acquired in some quarters. Chopping up a sample of a bagpipe pibroch and setting it to pounding techno, as he does in “Chanter,” should have been tantamount to sacrilege. Yet it secured his legacy as a national treasure. “When I was in high school and starting to learn to play the pipes, there was always a discussion about the naysayers in the folk scene, people who would be waving their finger saying you can’t do that, that’s not traditional,” MacDonald remembers. “And then Martyn Bennett completely blows them out of the water. ‘He’s not even playing live instruments. How the hell dare he?’”

2 x Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

By expanding the limits of trad, Bennett also opened the doorway for those young Scots who associated folk more with an archaic past than with youth culture. Spirals remembers mostly encountering ceilidhs in school which, as a teenager who was more drawn to Galloway Forest free parties, hardly endeared him to the traditional dances. For Cummins, folk music was what his parents listened to—“a bit twee and safe” compared to the drum & bass he was discovering in Dundee clubs. Hearing a fiddle spliced with jungle breaks and an MC was a revelation. “I was at a party at 7am and somebody put on the track ‘Liberation’ with Michael Marra. I was like, ‘What the fuck is that?’” says Cummins. “A lot of the guys I was hanging out with then were older, and they had all this ancient steam-powered gear—old Atari samplers and stuff. They were like, ‘This is this guy. He knew what he was doing.’ The musicality was there in the electronic side, the way it is with Aphex Twin or Boards of Canada.”

Drawn in by the potential of this hybrid sound, Cummins teamed up with fiddler Lewis Williamson, after witnessing him render the riff from The Prodigy’s “Voodoo People” on violin, and departed member Marco Salvatore Baressi; together, they laid the groundwork for what would grow into the six-piece Yoko Pwno. “Scottish music can actually be cool,” says Cummins. “It stopped being this twee thing and started being associated with club culture, sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll—all that fun stuff.” More than that, he continues, Celtic fusion’s explosion may even have helped to reshape Scottish identity. “National music and folk music come from the past. They depict an idealized version of the ideas that bind us together as a country,” he says. “The Celtic fusion scene took that and gave us something of a counterculture and, in doing so, made the way we think about ourselves as a country more diverse, more interesting, more forward thinking.”

2 x Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Certainly, that impulse was what guided Bennett. In the liner notes to Grit, he condemned the “misty-lensed and fanciful” evocations of Celtic culture he had seen multiply, presenting his record as a more “truthful picture” of the nation’s indigenous past. Jacobite elegies (“Why”) appear alongside songs long passed down by Scotland’s Romani Travellers—most memorably in the opening track “Move,” which samples Sheila Stewart’s stirring wail beneath a forceful 808 bassline. It was Bennett’s contention that the Roma, just like the Gaels, were fundamental to Scottish folk. “They have certainly been in Scotland for well over a thousand years,” his notes proclaim.

For much of his career, Bennett’s music sat alongside a growing revival of Scottish culture and political consciousness. In the same year that he was recording his eponymous debut album, he performed in Stirling Castle at the launch party for the blockbuster Braveheart (1995), a film that, in the years that followed, emblematized an increasing clamor for Scottish devolution. When the new Scottish parliament opened in 1999, one of Bennett’s compositions was commissioned for the opening ceremony—an appropriate accolade for a life spent recalibrating the Scottish mythos for an electrified, progressive era.

Few songs better represent the continuity between Bennett and today’s Celtic fusion scene than the piece that was broadcast that day from Edinburgh’s Princes Street Gardens, called “Mackay’s Memoirs.” When Real World Records reissued Grit in 2014, they chose a version of the song as the new album closer, which pupils from the City of Edinburgh Music School had recorded in 2005. Yoko Pwno’s vocalist and violinist, Lissa Robertson, happened to be part of that orchestra.

2 x Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

“I remember we took a bus all the way through to Glasgow. Martyn Bennett was supposed to be there that day, but we got there and they said, ‘Sorry, he’s actually too ill today to make it,’” she says. “It was my first time being in a studio session, with headphones on, and recording it over and over again. It was wonderful. Everybody’s in high spirits. And then on the coach back, the head of the music department got up and said, ‘Everybody, I need to tell you something. We’re so sorry we didn’t tell you this before, but Martyn Bennett passed away last night.’ It was a wee bit of a shock, but it meant all that bit more to be on that record.”

“Mackay’s Memoirs” would be Bennett’s last recorded work. He died from a long battle with cancer on January 30, 2005—a mere nine years on from the release of his first album. What would surely have delighted the virtuoso is that the genre he popularized continued to develop. Thanks to the evolution of studio recording equipment that democratized production for a new generation of artists, Celtic fusion has grown up.

“It’s become more sophisticated,” says MacDonald. “Part of that is people getting more accustomed to it. People are open to a broader range of ideas.” The track “Teannaibh Dlùth,” from Niteworks’s latest album A’ Ghrian, is a case in point, mixing a shuffling breakbeat and cascading bleeps with a moody Gaelic vocal. “I went through a big phase of listening to East London drill music. I got really into Headie One and people like that,” says MacDonald. “Innes [Strachan] had come up with this synth bit and then I had this idea to do this odd repeating pattern break, similar to what you get in some drill music.”

Compact Disc (CD), Vinyl LP, 2 x Vinyl LP

“At the moment there seems to be a really big resurgence to bring Celtic fusion up to date and merge it with things that are happening now, rather than copying things,” says McLaughlin, describing An Dannsa Dub’s own mission to reflect trends in the dub scene. “It’s making sure to tap into what that scene is doing at this moment in time.”

“For example, mixing psytrance elements,” Spirals adds. “We’ve been able to merge the basslines together, so you can choose whether you’re tuning to a dub or a trance speed. They’re both kind of present and hinting to each other and swapping between the two, which is something that’s been happening in the dub world in the last two or three years. In France, they call it ‘la dub,’ not ‘le dub.’”

That continuous appetite for invention has taken An Dannsa Dub to ever bigger stages—from Glasgow’s Celtic Connections (recognized as Europe’s leading roots festival) to Boomtown Fair, one of England’s biggest hubs for underground dance music, where the band whipped up a frenzy with 10,000 bass music fans. As Celtic fusion spreads beyond Scotland, its unique place within the global folk music scene has crystallized. “The amount of people that are involved in it and the caliber it is being done to, it’s so high,” says McLaughlin, “especially in young people trying to push things. It’s super exciting. I’ve not quite seen that anywhere else to the level that is here.”

“Ireland has a very strong folk scene, and it probably has a similar, if not higher, proportion of players. Yet, they don’t really have the whole fusion thing like we do in Scotland,” MacDonald agrees. “It was Martyn that kickstarted that movement, and then it’s weird how the two paths have diverged.”

Part of that distinction could be down to the particular way that Scots experience their folk culture, according to Cummins. “When we talk about folk music, we mean two things,” he says. “There is a definition of folk music, which is pretty loose, that’s the sort of thing you might find listed under folk or traditional in a record shop. But then there’s another definition, which is that folk music is a practice. It’s not something you can put on a stage or record on a CD. It’s a group of people getting together and playing this music.” The key to authentic Scottish folk, then, may not be a strict idea of how the music should sound, but the feeling it gives. You can hear it in Bennett’s wild, weird, Frankenstein-like productions—the background hum of a smoky pub where musicians improvise together is almost audible beneath the ecstatic pace of the underground rave (one track on Grit is fittingly called “Ale House”). Stuffy convention, meanwhile, is abandoned at the door.

“I was recently playing a rave in an Iron Age roundhouse,” says Cummins. “Some guy came up to me and was like, ‘I really like your band, and one of the reasons that I like you is because you do folk music, but you’re not twee.’ That’s the best compliment I could possibly have been paid. It should be cool and contemporary and sincere and diverse.”