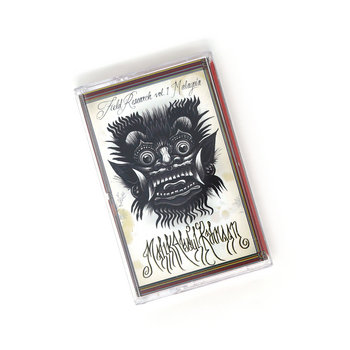

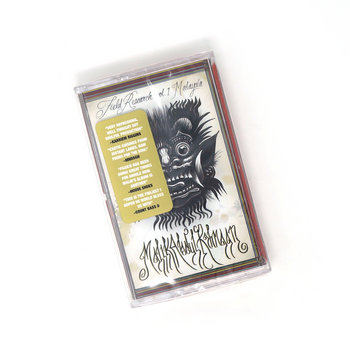

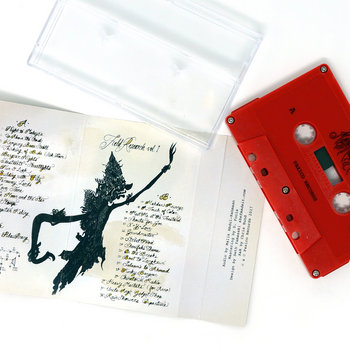

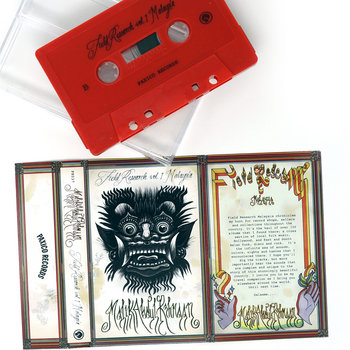

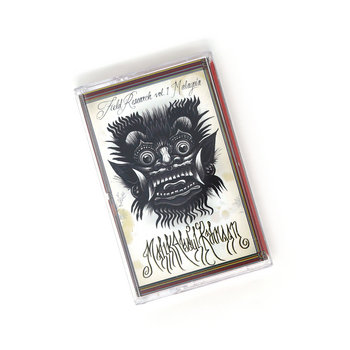

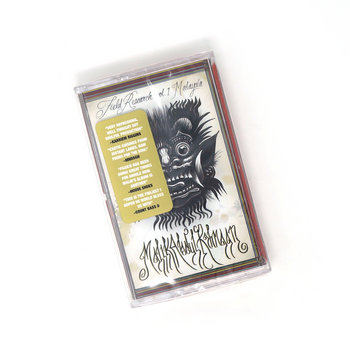

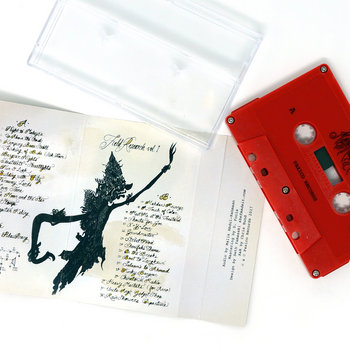

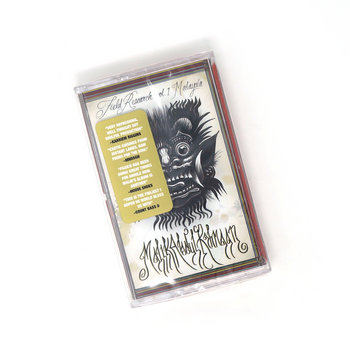

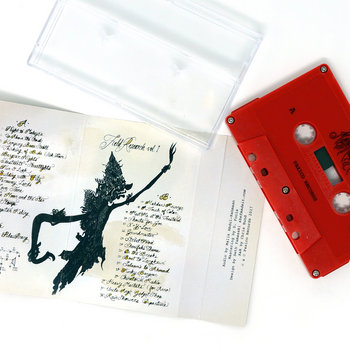

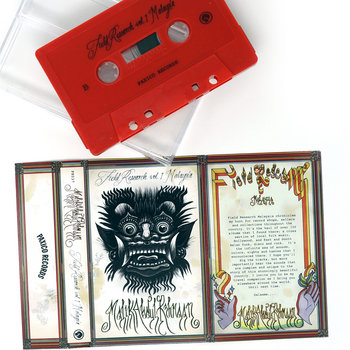

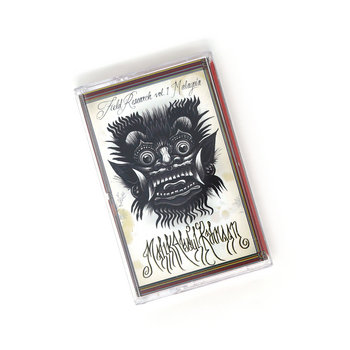

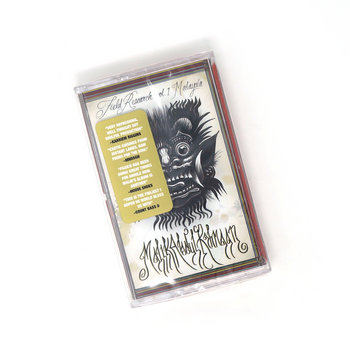

Malik Abdul-Rahmaan is a truly global citizen. Born in Texas, Abdul-Rahmaan spent his early adult years in the Air Force, stationed in Japan. Frequenting the legendary club Harlem in Tokyo’s Shibuya district, Abdul-Rahmaan found himself immersed in Japan’s rich and energetic hip-hop scene. After cutting his teeth producing soulful, dusty sample-based tracks for various Japanese rap acts, Abdul-Rahmaan returned to the U.S. and continued building up an impressive résumé that includes work with heavyweights like Ghostface Killah and progressive hip-hop label Paxico Records. Inspired by his time abroad, Abdul-Rahmaan conceived the Field Research project, a series of instrumental albums in which he captures the sound and essence of a specific country that he has visited, absorbing the local culture, digging up obscure vinyl and creating a beat tape inspired by each trip. Field Research: Malaysia, the first in the series, is an impressive start to this ambitious project, pulling from steamy Southeast Asian funk, Bollywood-style soundtracks, garage rock obscurities, and more. Abdul-Rahmaan has created a rich and kaleidoscopic listening experience that translates Malaysia’s deep musical traditions into cutting-edge future beats while still honoring the original source material.

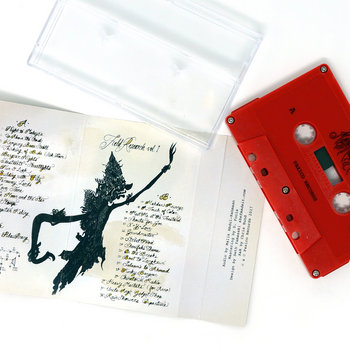

Cassette, 2 x Vinyl LP

I’m a bit familiar with your work, mainly through Paxico Records. Could you give a little background on how you started composing and producing music?

I grew up near Denton, Texas with an older brother who was a multi-instrumentalist and attended the University of North Texas there, which has one of the best music schools in the country. He kind of lit the fuse for me and would take me to some of his music labs and classes. I’ll always love and appreciate him for that. I took up percussion. He eventually got into beat making (this was the late ’90s) and I eventually followed, though it wouldn’t be for several years later. I ended up living in Tokyo for over seven years and that’s where I first learned to make beats and locked in my first credits.

Word. That’s amazing. Who were you producing for early on?

My first placements came via Japanese MCs who were on various different Japanese hip-hop labels. Japan has a massive hip-hop scene with some really quality MCs, producers and DJs when you dig under the surface. Living in Tokyo, I was constantly heading out to shows and meeting people involved in the hip-hop scene. I eventually produced a couple of singles for an artist named BES out there that caught some burn, and it kind of took off from there.

I’m curious—as an American, how did you start collaborating with artists like BES and Issugi From Monju? I know that you were living in Japan for a while. Were you just embedded in the scene there and that just led you to working with Japanese acts?

That’s essentially what it was. I mean, I had a truck and was mobile so every Saturday night I was driving down to Shibuya to go to Club Harlem to peep my man DJ Hazime at his party. Everyone who was anyone at that time would fall through. I had done quite a bit of research on the scene prior to even arriving so I kind of knew where to go, what to do, and who to check for. I could hear the newest music downstairs or peep DJ Muro upstairs. He would often tell me what records he was spinning and that helped me with my record knowledge and digging. Fridays, I was heading to Club Bed in Ikebukuro to catch live, up-and-coming acts and that’s where I linked with BES. I learned that having showcases there was a kind of rite of passage and BES held down a bimonthly party there called Monster Box with another MC called Kan. They kind of precede Issugi and his crew, Down North Camp, but it’s the same lineage. I learned to make beats on an MPC-3000 out there and by digging in their shops. Anyone who’s been to Japan knows they have some of the absolute best record-digging, period. I learned a lot about my craft and got my foot in the door simply by being around and soaking it all in. It was a really special time.

When you were hanging at Harlem and building with Muro and all those folks, around what year was this?

This was like 2002-2005.

I’d like to switch gears and talk about the Field Research project. How did you come up with the idea to do these kind of musical travelogues?

Really, through my time spent living overseas, my musical connections with people in those different places, and our enduring relationships that have been made possible because of those connections. A few years after moving back to the States, I began studying ethnomusicology at The New School. But long before that, I had this concept of music and communication deeply embedded in my mind. Whether it was the Philippines, Thailand, South Korea, Singapore, or Okinawa, Japan—or several other places I visited during that time—music was my portal into the different cultures I encountered and was the foundation for relationships that I forged. Like, everyone knows what a good beat is. And everyone in every country nods their head and taps their foot when they hear it. I wanted to cast a light on that universality that music holds.

Plus, I’ve dug for records in many places. Some people gauge a good trip on the food or the sights. I often gauge a good trip on how interesting the records I found there were. [Laughs] It gives me an insight into the people who live in that place.

No doubt, that’s a common thread that I’ve noticed in talking with crate-diggers. We tend to think about music in the context of genre and locality. ‘Oh, I found a bunch of psych joints from Japan. I sampled this jazz record from Brazil,’ etc.

It’s really true. I mean, the irony of it all isn’t lost on me. I was a young black man living in Japan, learning about hip-hop and Black music history through all these stores around Tokyo and Osaka.

That’s amazing, traveling far away yet somehow finding your way back ‘home.’

I think I said it the same way once to a friend, actually, but yeah. That’s what it is. I mean, in my early days I was digging mostly Black-American musical gems out of Japanese record shops. Nowadays, I’m more interested in piecing together their musical history and I’ve found some incredible music out there. Some of that will make it into the Field Research: Japan project, coming up next.

Dope. I’ve been bumping the Malaysian tape all week and it’s an amazing piece of work. Can you speak a bit about your travels in Malaysia, the music that you discovered and the process of putting together this tape?

Thank you kindly. That really and truly means the world to me. So, the entire idea to do a series blossomed from this one trip. My lady and I were going there for nearly three weeks and, obviously, I wanted to dig for some records. I don’t know why, but I had this idea that I would find some great music there. I also figured that I would hear some amazing things, so I brought along my field recorder. I did a little pregame work and tracked down a long running record shop in Kuala Lumpur through Facebook. But there really weren’t many. Once there, it kind of turned into a hunt with friends of friends kind of pointing us along to weird spots until we found exactly what we were looking for. There is a real mix of cultures in Malaysia unlike that which you see anywhere else in the world—Malay, Chinese, and Indian. But there are other cultures blended in as well. Geographically, Malaysia sits at an amazing crossroads with Thailand to the north, Indonesia to the South, India to the west, and the Far East to the…well, you know.

Cassette, 2 x Vinyl LP

On a cultural and culinary level, that makes for an incredible blend, and the music that I discovered was no different. Malaysian funk and soul ballads, garage rock, Bollywood soundtracks. Korean bangers and kung fu movie soundtracks. It was really my life in those crates. I really couldn’t have asked for a more diversified digging experience.

Yeah, it’s interesting, the tape is so diverse stylistically. Even if you’ve never been to Malaysia or know nothing about the culture, you can tell that it’s a really eclectic place musically.

I really wanted that to translate over. I was nearly in tears when I left. Up to that point, I had never really had a travel experience like that. The common decency and downright goodwill and positive energy that the people I encountered there radiated—the sun and all of the bright colors that grew naturally there. The food and [its] infinitely complex blend of spices and seasonings. And the way music seemed to float in the air everywhere. Whether it was the Islamic call to prayer (which was everywhere), Buddhist temples with loudspeakers blasting out chants and mantras, or all of the sounds in the markets and hawker stands that we frequented…that place was just downright musical. It had soul and a real rhythm to it.

So, when I decided to start flipping the sounds I found, I thought about how I wanted to share that experience in sound with people. I remember playfully thinking that I was gonna do what Anthony Bourdain does, but with sound. The more I thought on that, though, the more serious I got about it. I mean, why not? He goes to different countries and eats amazing foods, but the viewers can’t taste that. And I totally respect him for that. But unless you live in one of a handful of U.S. cities, the odds of people ever getting to taste what he’s eating are pretty low. But sound, that’s a different story. There’s far, far more ability to share within that. I mean, rhythmically speaking, what’s the one thing that all human beings share?

Ears?

Close. I would assert that after our ears were developed we all used them to hear our mother’s heartbeats. The first thing that we all heard was a rhythm, and it communicated something. That’s what sound is supposed to do. For babies, it’s safety and security. But there’s a whole universe of sound out there that communicates all kinds of things for people in different circumstances. I chose to start my project with the Azān, a sung Muslim call to prayer because it’s so ubiquitous in Malaysia. And I want folks to hear that. I live in a country and region of the world where Islamophobia is a real thing.

One of my best experiences was staying near Kampung Baru in Kuala Lumpur. I would wake up around five o’clock every morning in a state of bliss. The house I was staying in was in the middle of no less than seven mosques and they each broadcast a call to prayer. But since they were each a few seconds off from each other, it created the illest psychedelic reverb wash/call and response.

I still go back to that recording sometimes and just listen to that. It was so calming and peaceful—meditative, even. My hope would be that if people saw why I saw and hear what I heard, it would start to knock down some barriers that they’ve put up around themselves. Because sound—and by extension, music—has the power to do that.

—John Morrison