On the first track on Heavy Petty, the debut release from Maarquii, Marquise Dickerson sings about pushing boundaries. The lyric is about a foolish affair, but it could double as the mission statement for the EP itself. Oscillating between soulful R&B and club-centric hip-hop, the six tracks on Heavy Petty, out via STYLSS, are united by Dickerson’s lithe, expressive voice, equally adept at dispensing life lessons, posing threats, and celebrating love. It’s a record that is undeniably black and queer, with an attitude and lyrics that defy gender.

Prior to a career as a singer, Dickerson was both a drag performer and dancer for the popular Portland R&B band Chanti Darling. Maarquii began taking shape at the monthly club night Sad Day that brings together DJs, drag performers, and live cryers in an all-night celebration of sadness. It was there that Dickerson—a triple threat who sings, raps and dances—met JVNITOR members Derek Stilwell and Saint Michael. The trio were introduced after Dickerson performed an a cappella rendition of an Erykah Badu track, and began working together shortly after.

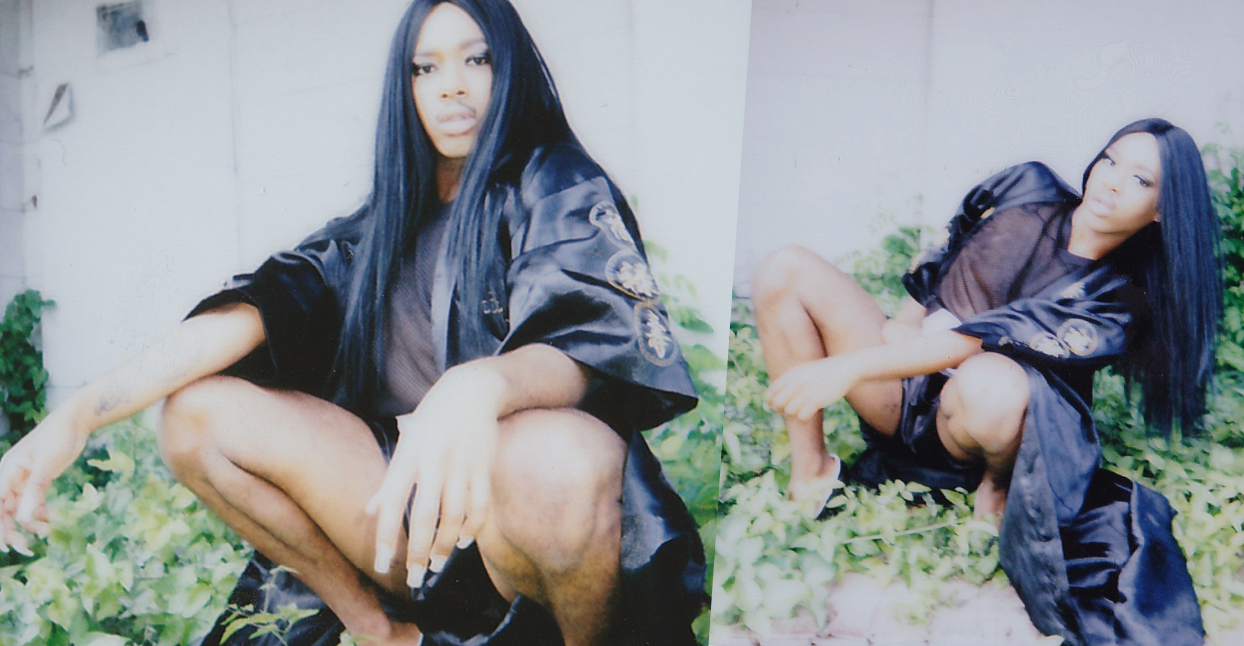

We talked with Dickerson about the real-life inspiration behind their songs, confronting otherness, and growing up gay in Arkansas.

You sing and you rap—does transitioning between the two come naturally for you?

I’ve always sang, and I’ve always written little ballads and stuff like that. It’s corny, but I really did start getting into rap right around the time Nicki Minaj was popping off. I’ve always loved hip-hop, and had a strong, strong pull toward female MCs like Missy Elliott, of course, and Kim and Trina. But when Nicki came out—she was doing it in this different kind of way, bringing in all these personas and stuff. And I was like, “I’m going to try this. I haven’t tried this sector of art, and I haven’t tried to write in this way yet.”

For a little while, I would read the dictionary every day and try to freestyle on my own and just hone those skills. It was really more for fun at first. Then I started looking up queer hip-hop artists and really the only queer rappers at the time that I was finding were Mykki Blanco and Zebra Katz. I was like, ‘Yes! Who are these creatures who are doing this hip-hop game, doing so much justice for queers like me who think, “We don’t have a platform, we don’t have a voice, there’s no one out here killing it on a level like that. We’re not represented in that way.”

Something about that struck me. It’s not really fair. I know so many gay folks out here who need that voice, and who need to be represented in hip-hop. Everybody loves hip-hop. We all love a nasty ‘ol dirty ‘ol hip hop beat. So I just started getting instrumentals offline and writing. Now it’s turned into something that I’m absolutely in love with. It’s just as much a part of my craft as singing. It’s a different vibe. I’m not an aggressive person by nature, so I feel like when I rap, it’s a chance to really hone that and get that out in a way that’s a bit more productive.

Speaking of lyrics and inspiration: In a lot of your songs, you adopt a bit of an aggressive stance. Are you singing from personal experience?

Literally every song on the EP is direct experience. The first song, “Don’t Crash”—there was really this man that I was involved with who wanted to spoil me, to take me all over the world. I was just like, “Look, I’m 19. I just moved to the city. This sounds very tempting, but I’m not in the space to do this right now.” The first line “Daddy came through, first dude on the avenue”—he was this lawyer, he flipped houses. I could really get used to this, but I always pride myself on being self-made and not just ‘Oh, daddy’s gonna fly me around.’ It was an experience for sure, but there’s definitely lots of truth in that one.

“Dam God” is not necessarily one experience in particular—it’s a conglomeration. There was a crazy, crazy week when I wrote that. I had tried to go stripping, tried to do amateur night at the strip club, and it didn’t work out, and I was really upset. My boyfriend ended up taking me out to get a couple drinks to decompress. That night, I was outside the hood of his car talking to a friend, and this girl came over and her and her boyfriend started yelling at me. They thought I was somebody else. I was yelling at them from across the parking lot like, “Look, you got the wrong guy. I’m not who you think I am.” They came up to me, and they were yelling at me and I was like, ”Look, I think this is just a big misunderstanding.” But they were drunk, so they weren’t getting it. And all of a sudden, the girl calls me nappy-headed.

I am the most calm, cool, collected person, but once you step over that line with me with disrespect, I turn. I see red. The country came out in me! I said, “What’s about to happen right now is you’ve got about five seconds to get up out my face or my hands will be in yours.” So that’s where, “Hands all in your face like mace” comes from.

On “Mean Tech,” the “She activated” line is a line that we—me and my friend Will, who’s the other dancer in Chanti Darling—say all the time right before we go onstage. “Oh, she activated. She’s about to call on the spirits to get her through this set.”

I think it’s the best way to do it. A writing teacher of mine once told me the best writing is when you write what you know. The whole record is personal experience. I wrote “Poplite” while my boyfriend was in the studio, right there next to me. It’s about him.

“I Am That” was really just about me moving to Portland. I feel like when I moved to Portland, I had a second coming out. I lived in Tillamook for so long, and there’s only so much of a nightlife scene you can get into in a small town. When I moved to Portland, I got exposed to so much nightlife in a really positive way. You hear horror stories about nightlife all the time, especially when you’re a country boy. “Oh, they get crazy out in the city.” But I really did meet so many beautiful creatures, and I always felt so safe around these people that I would go out with. My fashion game stepped up 200%. That song is really just about my country ass coming out to Portland and experiencing nightlife, and appreciating it, and being inspired by it. I feel like I grew up a lot when I moved to Portland, and acknowledged a lot about myself. But also on that same token, I learned to revel in being a little bit older, being able to make grown decisions and have fun at the same time.

You grew up in Tillamook, Oregon as well as Eldorado, Arkansas before moving to Portland. What was it like living in such small towns? Did you feel a sense of ‘otherness’?

I’ve always experienced people feeling some type of way about me, from a very young age. If it wasn’t about my sexuality, it was about my skin. I was getting bullied. From early as I can remember, I’ve always been beaten up for being gay. Once I realized that it was okay to defend myself, that I didn’t have to let people put their hands on me and talk to me all kinds of crazy, it really changed my perspective. I remember this like yesterday: We lived on a farm, [and] my mother pulled me in that big ‘ol yard and she said, ‘You gon’ learn how to fight today.’ Because I wouldn’t fight, I never liked to fight back. I don’t like violence, I really don’t. But she was like, ‘You’re not gonna be walking through this world getting your ass beat.’ My momma made me spar with her. [Laughs] I really appreciate her for that because it helped me gain the sense of self that I have now.

How do you keep up that inner strength? Did you know that as soon as you got out of Arkansas, you’d be making art and fulfilling yourself? Otherwise, you’d have been fighting back for the rest of your life—that’s just not motivating.

It’s kind of bittersweet, because I really did have to mature early. Not necessarily [in the way of] missing out on stuff young people do, but my mental state of being. I had to mature very quick. I don’t regret that, and I’m not upset about that at all. I am very very thankful for that fact. When I moved to Tillamook, I was in choir, drama, video productions—I was always doing something artistic, and so that was my saving grace. I knew that once I was done with high school, I would be making all of this art. But then also, I did get to a point where I had to relinquish a bunch of anger, because I was a pissed off, angry teen for a very long time, and I didn’t have a lot of friends that I trusted. I had to let that go. I really did have to get to a point where I didn’t let it affect me like that, because I realized it was killing me. Holding on to all that anger wasn’t doing nothing but stifling me.

It’s still something I’m working on. I don’t think it’ll ever go away completely, but with completing that record—“Dam God” is one of the most angry songs—it was really cathartic to feel that anger, and feel all of that pettiness and sassiness, and put it out there, and move forward, and learn from the ways in which it affected me. I can move through the world now that I have made peace with that, in a sense, and brought it to my own attention, “Okay girl, this is what it was. How can we be better?” It’s a big, mature thing. I’m all about my growth and trying to be better and better than I was before. I think that’s the ultimate point.

How did this collaboration come together?

I had done a music project a few years back called The Chronicles of Lolita Black— that was right when I was just like, ‘I want to write rap music, I wanna do something, I need to.’ So I put the feelers out into the world, and I ended up with another 6 song EP that was really… I just wanted to dabble into everything, and talk about coming to grips with my sexuality, my femininity. There’s a track on there called “Faggot Freshman” where I talk about being in high school, the things I experienced. It was really cathartic, but I also had so many expectations for the success of it. I didn’t know anyone. I wrote and produced it in Tillamook, Oregon. I had all these grandiose ideas of what it was gonna be like, and that didn’t happen. And I trusted my art with the wrong people, and I got burned and was really, really discouraged from music for a while, until I met Derek and Michael. I was really into their industrial sound. I really hadn’t been exposed to that, and I started to gain a really awesome appreciation for it [thinking] ‘How dope would it be to blend this kind of aesthetic, this kind of sound, together?’ It’s been great. I’ve had no expectations with the record, I really just wanted to have fun, and to share the art with people. And so that in itself, I’ve succeeded. Anything that comes after the record being done is really just blessings and cherry on top an already great pie.

That’s the thing about me, I love working with people who are kind first, and then their art is great second. I just want to work with some great artists who are sweet angels—[but] who can also get crazy when they need to.

—Nilina Mason-Campbell