Fawda Trio’s debut album is, in some ways, an unusual prospect. Building on the North African, ancient musical tradition of gnawa, it’s a music mostly listened to live—the krakab percussion’s thundering volume, paired with the simple, repeated basslines of the stringed guembri, have been honed over centuries to induce trance-like states in intimate, hours-long performances. Road to Essaouira translates those traditions onto record; channeling live gnawa’s meditative intensity, the album draws on outside influences—most audibly, jazz and hip hop—for a spiritually-minded focus guided by a wider musical approach.

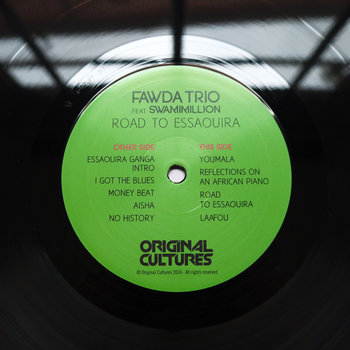

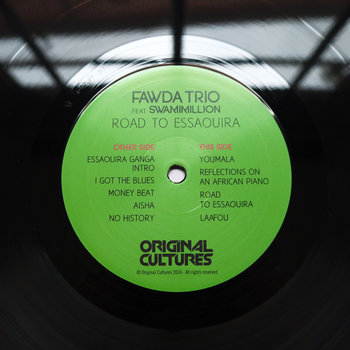

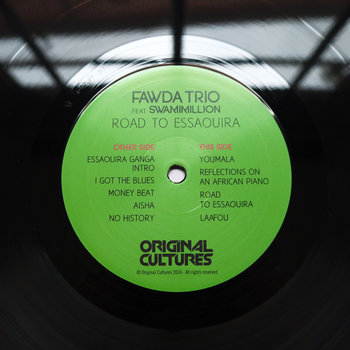

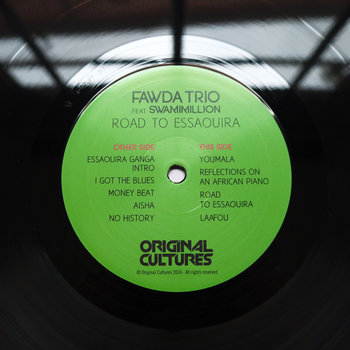

Vinyl LP

Based in Bologna, the band are outsiders to gnawa culture. The northern Italian city has a fertile jazz and experimental scene, with each of them playing together in different projects over the years. Reda Zine, who—for Fawda Trio—plays an electric version of the guembri, is originally from Morocco. Hailing from Casablanca, it was only after moving abroad that he discovered an interest in his country’s traditional music. Before that, he was involved in a homegrown culture of abrasive, heavy metal bands, as documented in Mark Levine’s book, Heavy Metal Islam. But it was a a move to Paris changed his perspective.

“I started opening my eyes, because Paris is like London—it’s a big platform,” he says. “I started meeting with people from all over the world, and giving value to my own heritage.” Moving there in 1999, it was collaborating with Moroccan and French-Algerian bandmates—in acts like the Cafe Mira collective—that awakened an interest in music which, previously, hadn’t felt relevant to him.

It soon prompted him to learn the guembri, one of the instruments central to gnawa. It was another two or three years, making regular return visits to the elder musicians in Morocco—known as maalems—before he would get to grips with the instrument. While it’s possible for anyone—tourists, local or otherwise—to simply buy a guembri, Zine went through the traditional teaching process, whereby it’s only when you’re deemed ready that the maalems present you with your own instrument. “You go from singing, to percussion, to playing,” he explains. “And when the masters tell you to play, that means you’re ready to play.”

Describing the role of gnawa within Moroccan culture, he says, “The masters are kind of like doctors—it’s like going to psychotherapy or something.” Drawing out the liberating, cleansing possibilities of the trance state that’s intended to be attained through the music, he says, “It helps you to metamorphosize, to funk, to throw away a lot of all this civilization bullshit, this smog [created by] superficial things.”

Zine later moved to Bologna, where he met his Fawda Trio bandmates. He and percussionist Danilo Mineo visited Morocco together, providing Mineo with his first proper introduction to its culture. For the band’s keys and synth player Fabrizio Puglisi, his knowledge stretched back further—a jazz piano teacher at two of Bologna’s academies, he’s long nursed interests in different kinds of African music.

Building up a repertoire of reimagined gnawa staples, along with new compositions, it was coming into contact with Original Cultures—a Bologna-based, non-profit music organization—that set the idea for an album in motion. Connecting the group with production duo SwamiMillion (aka LV, made up of Will Horrocks and Simon Williams), the London-based producers joined the band for a 2013 live show in Bologna. Then the following summer, through Original Cultures’ four co-founders’ pooled funds, along with a crowdfunding campaign and some additional money from Bologna’s city council, both SwamiMillion and Fawda Trio headed to Morocco’s coastal city of Essaouira to record the album.

Vinyl LP

Essaouira’s status as the unofficial gnawa capital made it a natural choice for the band. Setting up in the interior courtyard of Dar Souri, a cultural centre in the city, the space itself shaped the sound of the record. “There was an amazing reverb in the room, which we recorded from the first floor balcony,” co-producer Williams recalls. A means of incorporating a live feel to the recording, he and Horrocks also took up-close recordings of individual instruments, allowing them to rebalance the all-conquering sound of the krakab; using field recordings from around the city, too, an ambient undercurrent of marketplaces and moped engines fits with the travelogue idea suggested by the album’s title.

And it allowed them to visit the Sanctuary—or Zaouia—of Sidna Bilal, believed to be a black, African-originating companion to Muhammad, a figure to whom the gnawa community have ascribed their lineage. This, as Zine explains, is owing to the music’s roots in the trans-Saharan slave trade; transporting slaves from what would now be states like Mali, Chad, Sudan, to Morocco, Algeria and other Arab states, the slaves brought the culture of their homelands with them. “Gnawa was in the middle of this: with this art, with this music, they maintained their identity in the form of resistance.”

It was during that visit that they encountered Maalem Soudani, a meeting which would lead to him featuring on the album. Having discovered that a plan to meet one maalem after arriving had fallen through, they decided to drop their bags and take a tour of the sanctuary. Arriving at the well-preserved, ancient site, they entered to find a hushed audience observing a performance led by Soudani. Meeting him over tea at his shop the following day, he agreed to join them at Dar Souri, bringing his son and a student to jam and record. As a gesture, it affirmed the community-minded spirit that still prevails in the city. As Zine says, “It’s not just entertainment, it’s really healing music. A healing process.”

—Jake Hulyer