Traditional music can often be extremely…well, traditional. Often emphasizing preservation over innovation, practitioners of traditional forms can find themselves feeling stuck in the past. But pianist Eunhye Jeong, who has worked with Vijay Iyer and Tyshawn Sorey, and performed in an ensemble led by trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith, says that’s not the case with Korean music. “It really honors and respects a level of originality, she says. “That’s what I’ve found—it was never about preservation and following in your teacher’s footsteps. It was more about you bringing your own self, and reaching the highest level possible as a person, and to cultivate yourself and just become a better person. I find a lot of that idea in jazz as well.”

Between 2015 and 2019, Jeong studied the Korean pansori, an operatic form of musical storytelling, with Il-dong Bae, a master of the form. Pansori is a traditional Korean art form that lands somewhere between opera, ritual music, and flamenco or fado. In pansori a vocalist, often accompanied only by a drum, sings lyrics drawn from history and folklore. The pansori repertoire consists of 12 song cycles, but only half of those are still performed. “The main characters are mostly poor people and women,” Jeong explains. “They have hardships, they don’t have money, they get treated badly and then they overcome it and they forgive the people who did the wrong thing to them—things like that.”

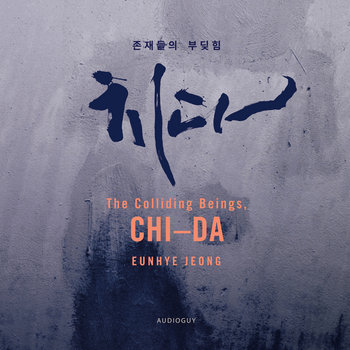

Compact Disc (CD)

On Jeong’s album The Colliding Beings, Chi-Da, Il-dong Bae delivers pansori lyrics over improvised music arranged for piano, cello, and drums. Jeong’s technique at the keyboard is shocking in its potency; her jackhammering left-hand figures bring to mind Cecil Taylor, Matthew Shipp, and the compositions of Galina Ustvolskaya. Cellist Ji Park creates long, keening drones that ripple and waver in the air, while percussionist Soo Jin Suh attacks the kit in a way that combines free jazz energy with breathtaking precision. She’s never trying to enforce a rhythm; instead, she drives the energy level higher and higher, feeding off the emotions of the other performers.

Il-dong delivers his lyrics in a powerful voice that can hold long droning low notes or rise to a violent, barking cry. Sometimes, he sounds like a monk, or like Keiji Haino; other times, he sounds like Ol’ Dirty Bastard. “He is more traditionally rooted than other contemporary Korean traditional musicians,” Jeong says. “Others who are younger [have] adapted more European free improvisational practices, or they can go more electronic, and fuse other elements into their music, but this guy, he sticks to a very traditional philosophy and principle around the music.”

“Chi-Da” is the animating concept behind the album—and behind Jeong’s work in general; the word also appeared in the title of her 2018 solo piano album. It is a term meant to describe collision. “You hit something, and you create a sound. So that’s the basic principle of making any kind of music, and that’s the core of the project—chi-da. The solo [album] was the chi-da between me as a pianist and the piano, the instrument. The new album is about the collision between the other people—the four instrumentalists. We have different backgrounds, our interests are different, but then we bring whatever we had in our musical or life context and instead of compromising any one of our sensibilities, we try to create a new sound.”

Some of the tracks on The Colliding Beings, Chi-Da are radical interpretations of traditional pansori songs, recontextualized and re-arranged. “Sarang-ga,” from the chunhyang-ga song cycle, is combined on the album’s first track with “Jeogori,” a children’s song that students in the Jo-seon classes in Japan sing. The Jo-seon people are Koreans who live in Japan, but they are citizens of neither country, having arrived there after World War II, but before the Korean War, when their former homeland split into North and South. “They still have this mentality—they maintain the history of loss of the nation and loss of the authority over our own country and things like that,” Jeong explains. “Il-dong actually went to visit them and was very impressed by the song that the schoolchildren sang for him. So he took the lyrics and made it more pansori, but the lyrics are the same.”

Compact Disc (CD)

Another piece, “The Sacrifice,” is a tribute to the victims of the 2014 Sewol Ferry disaster, in which nearly 300 Korean schoolchildren died; Il-dong performs an adaptation of famous Korean poet Kim Sowol’s “Mother, Sister.”

Collaborating with a pansori singer enabled Jeong to play high-level, freely improvised music for an audience that might never be exposed to that kind of expression under other circumstances. “The Sacrifice,” dealing as it did with one of the worst tragedies in recent Korean history, was particularly well received, according to Jeong: “I saw some people crying. A lot of people there hadn’t really experienced free improvised music before but they still felt connected to it, because he was singing a lot of the numbers they might know, but also we were delivering some of the stories that we [Koreans] share together.”