From its grand opening in 1976 until the mid-2000s, the imposing Palast der Republik (Palace of the Republic) stood on Spreeinsel, the small island that bisects the Spree as it flows northwest through central Berlin. Under the auspices of Erich Honecker, the leader of the Socialist Unity Party and by extension the single-party state of East Germany, construction took nearly three years and well exceeded its budget of 484 million Ostmarks. It was the most expensive building the German Democratic Republic—the GDR—ever built, with an enormous bronze glass facade and thousands of pendant lights suspended from its ceilings. East Berliners jokingly referred to it as “Erich’s lamp shop.”

As was common among the era’s socialist-minded public architecture, the Palast was multi-functional, designed to facilitate the holistic cultural and political education of the citizen. Besides federal offices and parliamentary assembly chambers, it contained a bowling alley, a cinema, art galleries, 13 restaurants, an indoor pool, a disco, and a rooftop ice rink. Festivals and performances were held regularly in its two auditoriums, often arranged by the Freie Deutsche Jugend (FDJ), the lone state-sponsored youth organization.

One such event was a 1986 FDJ music and theater festival headlined by the British blues rock band Ten Years After. Brothers Ronald and Robert Lippok were in attendance, on hand to provide musical accompaniment for a staging of Henryk Ibsen’s five-act play Peer Gynt. Once finished, the brothers snuck their instruments and the rest of their band through a back entrance. Ornament und Verbrechen played for roughly 40 minutes in the middle of a foyer. No encore.

This was entirely illegal. It was also so far outside the realm of reasonable possibility that no one asked questions. “It was in the eye of the storm,” says Robert Lippok now. “Nobody could imagine that there’s a band playing illegally in the Palast der Republik, the most looked-after building in the city.”

Vinyl LP

By this time, the Auftrittserlaubnis—the mandatory state-issued performance license granted to bands following an acceptable audition; something Ornament und Verbrechen most certainly did not possess—was old news. It was handed down in November 1965, just after Leipzig youth, protesting a citywide clampdown on local beat bands, nearly rioted when the police arrived with dogs and water cannons. The initial ban was an attempt to stymy the supposedly pernicious influence of beat music and the British Invasion specifically; the national Auftrittserlaubnis targeted Western musical decadence in its totality.

Of all the measures enacted to keep the decadent West at bay, the very literal closed border was the most effective. Technically speaking, there were two western borders: the inner German border that stretched 858 miles from the Baltic Sea to Czechoslovakia, and the Berlin Wall, a heavily-mined sand strip encased by 13-foot concrete barriers and fortified with guard towers. Western records, music magazines, stereos, recording equipment, and the like flowed freely across neither.

Soundwaves, however, did. In the Wall’s looming shadow towards the close of the 1970s, a small cohort of young East Germans tuned into the English-language station Radio Luxembourg, which broadcasted the banner British punk bands of the day: The Clash, The Sex Pistols, X-Ray Spex, The Buzzcocks. They co-opted British punk’s sneering nihilism—no future—and redirected it toward its opposite extreme: too much future, a rallying cry against the state’s intense involvement in every stage of their lives as socialist citizens in a planned economy.

If the British punks had nothing to lose, then the East German ones had everything to lose—a somewhat appealing prospect when it’s everything that you despise. “Our generation was fed up with the GDR, the whole system,” says Bernd Jestram, guitarist in the arty East Berlin punk band Rosa Extra. “There was no drive to rebuild it or think about how to make it better, to renew it.” Out of this climate sprung overtly political bands like Planlos, Namenlos, and Wutanfall, whose singers railed against society and the state at illegal shows held in parks and Protestant churches.

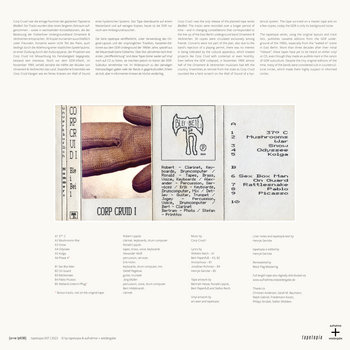

Cassette

But almost as quickly in the early 1980s, an artistic fission began to form within the burgeoning musical underground. It was partly stylistic. Darkwave, experimental, and post-punk moved in, helped along by John Peel’s border-hopping transmissions of Throbbing Gristle, Bauhaus, Killing Joke, and Cabaret Voltaire. It was also ideological. The naked political rage of punk’s first wave had accomplished little besides the interrogation, imprisonment, conscription, and forced emigration of many of its adherents. And realistically, there was only so much one could scream into a microphone about it. Meanwhile the relatively small size of the scene had enabled a musical and literary intermingling, suffusing East German punk with avant-garde poetry.

Helmed by Jestram and Günther Spalda, Rosa Extra was among the first to outsource its lyrics to the poets in the scene, namely Stefan Döring and the late Bert Papenfuß-Gorek, who passed away in August. Jestram had moved to Berlin from the Brandenburg countryside at 16 and taken a job heating the meeting rooms of a local chess club. It paid, required minimal time (especially during the summer), and provided him with an Arbeitsvertrag, the all-important work contract in a state where unemployment was considered suspect and asocial. He fell into the underground circuit, picked up a guitar and formed Der schwarze Kanal with Spalda in 1979, then Rosa Extra in 1980. He made friends with the Lippok brothers, and Ronald joined Rosa Extra on drums.

Agents from the Ministry for State Security (the Stasi) approached his parents about their son’s behavior first. Jestram didn’t care, but it was only a matter of time. In 1983, Rosa Extra recorded several songs for DDR von Unten, a compilation of East German punk intended for publication in the West. Tapped to help coordinate the project, the poet and underground man-about-town Sascha Anderson made a full report to his Stasi minders. Spalda and Jestram were collected and threatened with a ten-year prison sentence if they didn’t hand over the session tapes.

They balked. “To be honest, I didn’t want to go to prison to make a record,” Jestram says.

Eager for something “more experimental, more noisy, more open-minded,” Jestram started Aufruhr zur Liebe. “This punk rock style, for me, it was over,” he says. By 1986, so was his time in East Berlin. He’d refused to become an unofficial Stasi informant and told his friends he’d been ordered to do so. “It didn’t take too much time until they threw me out,” he says.

This wasn’t uncommon. The underground was continually plagued by the abrupt departures of its members, spirited away by police and carted off to military service, tossed into prison, or, as in Jestram’s case, deported to West Berlin.

But the 1980s carried on, and so did the scene. The musicians who filled out Ornament und Verbrechen’s lineup, always in flux around the Lippok brothers, spun off into Corp Cruid, The Local Moon, and Neuntage Alt. The poetry got denser, and so did the music. Klick & Aus interspersed their elemental, ghostly post-punk with abrasively cheery field recordings of Christmas markets. Der Expander des Fortschritts, formed in 1986, superimposed their shambolic, expressionist pop abstractions with cynically deployed socialist slogans. AG Geige and Kartoffelschälmaschine emerged from Karl-Marx-Stadt, the former with multimedia “trickbeat” sets performed in elaborate costumes, and the latter with deliberately alienating noise sets requiring three saxophones.

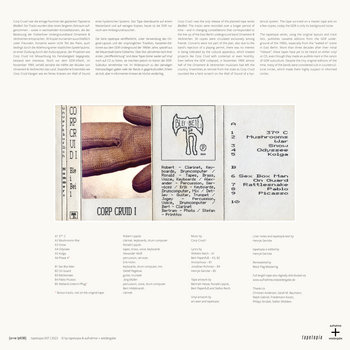

Vinyl LP

Karl-Marx-Stadt was an underground hotbed unto itself. The city’s proximity to the inner German border put its residents within listening distance of Bayern 2, the West German station that broadcasted Public Image Ltd., Wild Man Fisher, and The Residents from its Munich headquarters. Sufficiently inspired, Claus Löser and Florian Merkel formed Die Gehirne there in 1983. They recruited Frank Maibier, a painter, to read August Stramm poems about trench warfare over their manically improvised no-wave sketches, which they recorded onto West German cassettes Merkel’s aunt brought from Stuttgart during sanctioned family visits.

Music circulated the East German underground exclusively on tapes. This was a matter of convenience, not thrift. A single poor-quality cassette ran for about 20 Ostmarks. Monthly rent on a one-bedroom flat, for comparison’s sake, ran for about 25. If you could scrounge up a few West German marks, you could buy better quality cassettes at Intershop, the government-run stores carrying West German products. Otherwise, you made do. The Lippok brothers raided their parents’ cassette collection, recording Ornament und Verbrechen’s music over their mother’s old Mirelle Mathieu albums. (No teenagers were grounded in the making of these tapes. “We asked first. We were quite nice kids I think,” says Lippok.)

The ironic upside of the Auftrittserlaubnis, which only some of East Germany’s underground acts ever applied for, was its built-in repressiveness. The inherent illegality of performing in the first place lessened the compulsion to spend all your stage time sending up the system. “It was not political in the sense that we were onstage and cried, ‘Kill the government!’ But it was political that we were onstage,” says Merkel.

There was also some fun, quite frankly, to be had in being a bohemian enemy of the state.

“It was a bit like being Harry Potter and fighting the evil. When you’re a teenager you don’t give a fuck anyways,” says Lippok. “So it was also fun to fight against the government and the police. It was fun to make illegal activities and to try to organize shows which did not get busted by the police.” (Most did. The cops pulled the plug on Klick & Aus’s live debut after just 15 minutes; Jestram can’t recall a single Rosa Extra set that wasn’t busted.)

Lippok was 23 when he left for West Berlin in January 1989. The Wall fell ten months later, and the GDR was formally dissolved in October 1990. The East German underground, always something of a Notgemeinschaft, or emergency community, dispersed. Finally able to travel freely, many did. West Germans and young people from across Western Europe, the United States, and Canada flooded in, plunking down in vacant flats and storefronts. Out of this influx came what remains the predominant music culture of Berlin: not clanging experimental poetics and choppy buzzsaw punk, but house, jungle, breakbeat, and techno—music to rave to, in short.

Henryk Gericke grew up in East Berlin with a view of West Berlin, its rooftops visible out the window of his father’s 19th floor apartment on Fischerinsel. He worked at the print shop of a film distribution company and, beginning in 1981, fronted the punk band The Leistungsleichen. By the mid-1980s he was running a one-man clandestine press out of the print shop, producing small runs of his own Surrealism-inspired magazine Caligo and of ART 27, a political samizdat magazine cheekily named after the constitutional article granting press freedom. “That was a great part of my Stasi archive,” he says.

Gericke still lives in what is now the former East Berlin, in an apartment set back from the street lined with books and records. Several shelves are dedicated to storing LPs in the Tapetopia series, which he has coordinated since 2019. He’s an authority on East German punk, having assembled multiple compilation records, co-curated the 2005 exhibition ostPunk! Too Much Future, and co-written the 2006 documentary of the same name. And now he’s done. “For me it’s really over,” he says. “I give no more interviews about punk rock.”

The rehashing of GDR punk largely exhausted, Gericke started the Tapetopia series to shift focus to the scene’s lesser-known and more experimental acts. Tapetopia is at base a corrective effort, one Gericke hopes will elevate this music within the subcultural legacies of the GDR and divided Germany at large.

“If you have exhibitions about the subculture in Germany, it’s always an exhibition about the West part of the subculture,” he says. “The East part gets a corner, and always with Ornament und Verbrechen instead of the whole scene.”

There’s a preservational element at work here too. Gericke calls Tapetopia a “physical protest,” one that manages to capture the sound of “a forgotten culture” before the last of the tapes slide into oblivion by way of a neglected drawer.

And on top of it all, it’s personal. He saw these bands in real time, and many of the musicians are still his friends. When Ronald Lippok unearthed the master tape for Corp Cruid’s off-kilter, industrial synthwave record at the back of a cluttered shelf last year, he called Gericke straight away. The remastered reissue went out in December.

Vinyl LP, Cassette

“It’s a hard project. I spent so much time, love, and money on this project,” he says. “It’s, for me, really important to sell the records, to leave it in the world. Like kids, like children. Perhaps it’s a bit pathetisch. A bit emotional.”

Thirty-plus years later, there’s shockingly little physical evidence besides Gericke’s reissues. Jestram periodically screens a short film of Rosa Extra performances shot on Super 8. The Lippok brothers still occasionally perform as Ornament und Verbrechen.

But that’s about it.

Apartments in Prenzlauer Berg and Mitte, the districts where Berlin’s experimental underground flourished, are now among the most expensive in the city. The concrete remains of the Wall have been repackaged as tourist attractions for selfies or sticking your gum. Karl-Marx-Stadt is once again called Chemnitz, reverting its pre-GDR name following a 1990 referendum.

And the Palast der Republik, where Ornament und Verbrechen orchestrated arguably the East German underground’s most subversive performance, is not only long gone but virtually memory-holed. Demolished between 2006 and 2008, it was replaced by a faithful recreation of the Berlin Palace, the baroque royal residence that occupied the area before it was gutted by Allied bombs in 1945 and razed in the early 1950s. The contemporary recreation includes a copy of the dome originally commissioned by Friedrich Wilhelm IV, the Prussian king responsible for the bloody suppression of the democratically-minded Revolution of 1848.

Maybe it’s a metaphor. It’s certainly a statement. In any case, which aspects of East German history get preserved—and how, and by whom—is fraught with contradiction. The cohort of artists who populated the East German underground in the country’s final decade aren’t nostalgic per se, but they share a distaste for the papering over of history and the shunting off of East German culture, sub- or otherwise.

“Building a castle and pretending there never was a Palast der Republik or there never was a ruin or there never was a war—this is a war, to me, against truth,” says Lippok. “If I had a tank I would knock this thing down.”