“I was really agitated in my 20s in terms of the desire for social change,” says dawson vocalist and guitarist Jer Reid. “I had a lot of rage. It really felt like I had some things I needed to communicate, and noisy DIY music was a great way to do that and make connections with people, feel solidarity.”

Compact Disc (CD)

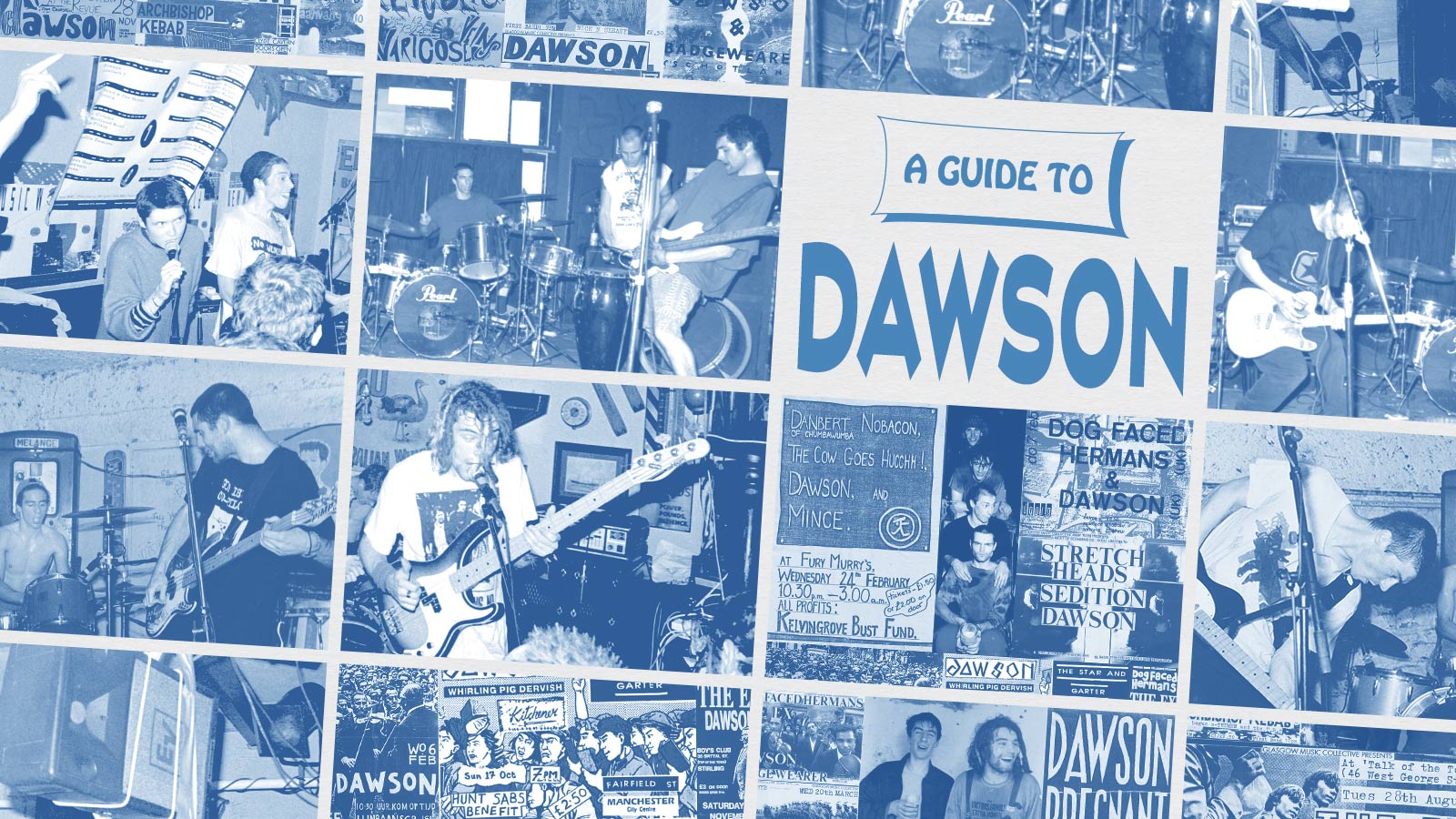

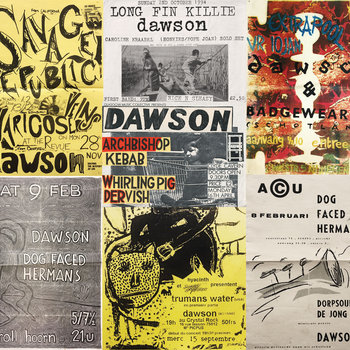

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Scotland was a hotbed for DIY noise, led by bands who fused post-punk’s experimentalism with hardcore’s intensity: Dog Faced Hermans, Stretchheads, Archbishop Kebab, Nyah Fearties, and of course, dawson. Too abrasive, weird, and socialist to fit with the dominant indie trends of the time, these acts have tended to be written out of the official histories. But their wild, inspiring bodies of work are still out there, waiting to be discovered.

Enter Australia’s Sorcerer Records, who have compiled the entire dawson discography—including previously unreleased live tracks—into a single 2CD set. Between 1989 and 1994, the Glasgow trio released three albums and three EPs. At its core, their music is a ferocious blast of barked vocals, razorwire guitar, punk-funk bass, and high-velocity drumming. Add in hip-hop, dub, and free improv influences, a dash of African pop and Eastern European folk, and the end result is the sound of punk futures being born.

It all started in the mid-’80s when Reid and school friend Ali Begbie started making a racket at home in Bearsden, near Glasgow. “We were both rubbish, but it didn’t matter,” laughs Reid. In time, they started writing their own material, inspired by the music they heard on John Peel’s BBC radio show: scratchy, discordant guitar music like Big Flame and A Witness, infused with hip-hop, reggae, and African music. While still at school, they’d talk their way into legendary Glasgow club night Splash One, where they came face-to-face with Sonic Youth, Firehose, and 23 Skidoo. All of this shaped dawson’s nascent sound. “Tom [aka drummer Graham Thomson] was really into James Brown, which brought a really nice funkiness that I don’t think me and Ali would necessarily have had,” says Reid. I’ve been thinking about how, even though it’s noisy guitar music, maybe it was always music to dance to as well.”

Dawson played their first gig in 1988—“seven songs in eleven minutes” as Reid recalls in the discography liner notes. Like The Minutemen, dawson jammed econo, packing multiple ideas into raw blasts of noise. The elements are all there on 1989’s Romping Egos EP, released on Reid’s own Gruff Wit records, but it’s with 1991’s debut album Barf Market: You’re Ontae Plums, that the trio’s imagination runs riot. With Stretchheads’s Richie Dempsey replacing Thompson, the band stepped up a gear, racing through stop-start structures and dynamic shifts. On Barf Market and its 1992 successor, How To Follow… Dempsey’s skills as an engineer enabled a level of studio experimentation not often associated with DIY punk. “We were trying so many different things in the studio,” says Reid, “especially in terms of having dub and hip-hop influences. We were trying really interesting mixing techniques. It’s that classic creativity of being 22 in the studio and not knowing what the rules are, just doing what was exciting.”

While most of the songs were fully realized before recording, others were constructed in the studio. The playful experiments of Barf Market take in loping breakbeats, comedy snippets, and home-brewed techno. “We were pissing ourselves at all the stupid things we were coming up with,” recalls Begbie, “You would hold it together to get to the end of the song.”

Compact Disc (CD)

Their techniques grew more sophisticated on How To Follow, as the band weaved samples of Malian pop and performance poetry into carefully constructed songs. While motivated by curiosity and adventure, Reid acknowledges that their approach was of its time. “You cringe a bit listening back because there just wasn’t a dialogue about the appropriation of other cultures then. Sampling, especially at that point, was just people grabbing what they wanted from where they wanted.”

By their third album, 1994’s Terminal Island, dawson relied less on samples, having developed their chops touring Europe and the U.S. “It started to be a bit more exploratory and tightened up,” Reid reflects. While staying on as studio engineer, Dempsey had passed the drumsticks to Robbie McKendrick, whose supple playing was augmented by carnival flourishes from percussionist Craig Bryce. The opening, “Post Preposterous Pre Perfect Post Prefect” shows how far they’d come: a spectacular eruption of droning feedback and frenzied guitars, darting from post-punk scrabble to sputtering noise by way of a nimble mbaqanga-inspired breakdown.

In true DIY style, dawson’s wildly inventive and powerful music is informed by their left-wing politics. Their lyrics take on imperialist wars, consumer capitalism, racism, and misogyny, the invective cut with a healthy dose of Glaswegian absurdism. “From Bearsden to Baghdad (via the Erskine Bridge)” is a vivid depiction of the first Iraq War as mediated through Western television, with the mundane details of domestic life contrasted with the horrors of modern warfare. Environmental concerns provide another running theme, be they the polluted rivers of “Fifty Years” to the mass extinctions Keebé Begbie sings about on “Booger Hall.”

Reid went through a period of disillusionment after parting ways with his bandmates. “I never really thought the music amounted to that much, but that’s because I was looking at it through the lens of a desire for widespread social change,” he says. “I loved the music that was around us—Dog Faced Hermans, Stretchheads, and all our other peers. And I could definitely see the change to the world those folks [were making].” Being away from music made Reid miserable. “So, I went back and haven’t stopped doing music since then.” A cornerstone of Glasgow’s underground music community, Reid has been involved in numerous projects over the years, from collaborations with dancers and poets to the structured improvisations of Bravest Boat. A member of Glasgow Improvisers Orchestra, he regularly plays in duos with saxophonists Raymond MacDonald and Tony Bevan. He’s also reunited with Begbie and Dempsey as Sumshapes, playing entirely new material.

Reid recently published a book, Days and Diary Entries, gathering ideas, lyrics, and poems from his teens to the present day. “I’m a bit allergic to nostalgia,” he confesses, “but I’ve been really enjoying looking back, especially old photographs and making connections, sharing memories with Ali.” Discussing dawson’s apparent erasure from official histories, he sounds like a philosopher: “Those subcultures that we were a part of, we were not interested in being well known.” Another issue, Begbie notes, is that dawson didn’t really fit in: “It wasn’t straight-up punk or twee indie pop.” Nobody was queueing up to give dawson gigs, Dempsey recalls, so he and his peers had to do it themselves, leading to the formation of Glasgow Music Collective, which hosted globally known bands (Fugazi, At The Drive In) alongside local acts. “I think it’s maybe not so much written out of history,” Dempsey adds, “as it was never really recognized as a part of things, apart from about 100 die-hard people in Glasgow who are like, ‘Man, that was amazing.’”

To launch the discography, Reid, Begbie, and Dempsey announced a one-off dawson gig in Glasgow. Such was the demand, they swiftly organized a second date, with support from some of the younger artists Reid has championed. “It doesn’t feel like it’s coming to an end because it hasn’t really restarted,” Reid relates, “but it’s definitely nice to tie it all together.”