Some time in the mid-’90s, Tim Wright found himself onstage with The Chemical Brothers. Amped up by the music and “kind of standing around, kind of dancing,” he pumped his fist to the UK crowd and they roared. He was pretty sure no one in the rowdy audience knew who he was.

The Brothers introduced him as CoLD SToRAGE, a musician responsible for scoring the new Playstation game Wipeout. The crowd roared again.

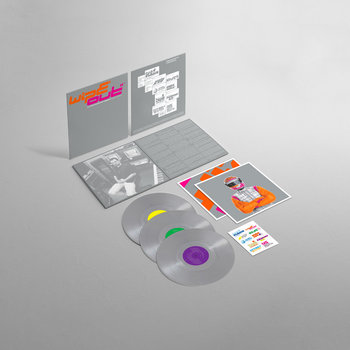

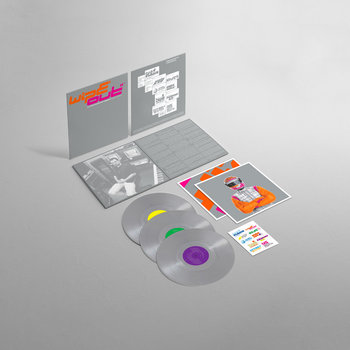

Vinyl, Compact Disc (CD), 2 x Vinyl LP

“They were so drunk they’d probably ‘whoo’ anything,” Wright remembers. A woman towards the front of the crowd flashed him her breasts. For a musician and developer who spent most of his time staring at computer screens in the damp back room of a Liverpool games studio, “It was all very strange,” he says.

A year prior, Tim Wright might have told you that he hated electronic music, though he wouldn’t have really meant it. “I was disinterested,” he clarifies now from the living room couch at his home in Switzerland. “Which is probably worse than hate.”

By the time Wipeout crossed his desk, Wright was an established games musician. Born and raised on a farm outside of Rexham, Wales, Wright wound up in Liverpool in his early 20s. It was there, after a chance encounter in a computer shop, that he became enamored by the thriving European “demoscene,” where amateur programmers, artists, and musicians created short computer programs meant to one-up each others’ technical ability or artistic ambition. Wright’s own three-person crew, Dionysus, created a comedic and artful short narrative about a stranded alien named Puggsy. Wright helmed the game’s sound effects and hyper-melodic soundtrack, which made full and frantic use of the Amiga’s four-channel music capabilities.

On the strength of the Puggsy demo, all three Dionysus members were hired full-time at Psygnosis, a Liverpool studio known for games that were both deeply playable and stylish. The crew would accept a buyout for their stranded alien game (which would go on to be a cult classic for the Amiga and Sega Genesis), but Wright helmed the audio on a number of enduring Amiga games at Psygnosis, including titles from the Shadow of the Beast series, the cult classic Powermonger, and a game he describes as a sort of nightmarish rush-job, Lemmings. “Our business cards when we were at Psygnosis didn’t say ‘musicians,’” he explains. “They said ‘Sound Artist.’ We would program, we’d write little utilities to break up files into smaller sizes and whatnot, and we were creating sound effects.”

Wright was helming all of these roles amidst the biggest technological sea-change in the history of video game audio: the transition from computer disks and console cartridges to compact discs, which functionally ended game audio’s technical limitations. Wright, for one, had learned to love the limitations of making music on the Amiga. “Initially, it was a learning experience and you made the worst music ever, but you learned partly through experimentation and partly through dissecting,” he says, explaining that game musicians of his generation would literally break apart each other’s sound files on the Amiga to see how they’d achieved certain effects or musical flourishes. “You picked up all these hints and tips from other people’s work,” Wright says. “Standing on the shoulders of giants, I suppose.”

Suddenly, though, game musicians like Wright were “now competing with the likes of all the pop and rock bands.” By all accounts, Wright handled the transition well. His first foray into CD game audio was a port of the game No Escape–itself a movie adaptation–from Genesis to the Sega CD system (Mega CD in Europe). The project found him in close communication with famed film composer Graeme Revell, who provided samples for Wright to adapt. When he played the near-finished music for the game’s producer, his response stuck with Wright. “This is too good for the game.”

Vinyl, Compact Disc (CD), 2 x Vinyl LP

Wipeout, though, was a game with higher expectations than games Wright had worked on in the past. Sony acquired Psygnosis in 1993, and Wipeout was to be a key UK launch title for Sony, whose new foray into home consoles, the Sony Playstation, aimed to bury any conception of console games as “kid stuff.” Wipeout would come wrapped in bold packaging by Sheffield marketing firm The Designers’ Republic. The game—or a sexed-up evocation of it—made an auspicious debut in the big-budget techno-thriller Hackers (1994). The advertising campaign felt new: copies of the game were playable in clubs and rave chillout tents. One print ad, which depicted two seemingly unconscious models with blood dripping from their noses, frightened parents and was accused of embracing drug culture (the capital “E” in Psygnosis’ styling of Wipeout didn’t help matters).

“It did strike me at the time, ‘Shit. They’re throwing a lot of marketing money at this game,’” Wright says. “I think they saw it as gaining an audience. [Sony] already had all the geeky gamers, and now they were going to get all the chic cool people who are clubbing.”

Part of the game’s outsized marketing budget included in-game advertising from the nascent energy drink Red Bull. “These little fridges started appearing in the development office stacked full of Red Bull and I’m looking at it going, ‘What’s this?’” Wright remembers. He found the beverage “fruity and sugary but with a sort of darkness underneath” and took a handful to his studio while he worked on Wipeout. His fellow Psygnosis Sound Artist Mike Clark found him, crazy-eyed, his head hanging out of his studio window to examine how the sound traveled through walls. “I’m just really into the music, Mike, I don’t know what it is,” he told Clark, who asked how many Red Bulls Wright had consumed in the last hour. “Like six?”

While he had worked on some industrial music for his previous score–for the eccentric mech shooter Krazy Ivan–Wright says making the music for Wipeout meant going out and embracing club culture. That and buying “a shit-ton of sample CDs” and learning the intricacies of a Roland JD-800, which had “all these fantastic squelchy sounds.” Over the course of just a few months (and with a little help from caffeine), Wright went from EDM know-nothing to full-fledged recording artist with a nom de plume (Cold Storage, stylized CoLD SToRAGE) and snazzy logo.

Almost 30 years later, Wright’s contributions to Wipeout remain sonically intriguing and compositionally ambitious. “Cairodrome” melds club energy with exotic samples and crowd sounds, some of it pulsing and some of it frantic. “Cold Comfort” uses its breakbeats as organic texture and then lets them drift out of the mix in favor of scrambling synths and dreamy bells. These songs each contain multiple movements. Wright played the sprawling “DOH-T” for a friend while he was working on the soundtrack. “That’s great, so you’ve got those five tracks now and you can elongate them,” she said, to Wright’s puzzlement.

It wasn’t just Cold Storage creating music for Wipeout, though. Sony had leveraged its licensing muscle to bring electronic heavyweights like Orbital, Prodigy, and the Chemical Brothers on board as well. It’s a testament to Wright that his tracks not only stood their own against these known quantities, but many of them (particularly “Messij” and “Canada”) became fan favorites. I bought the Wipeout official soundtrack. (I, for one, felt a bit ripped off when I bought Sony’s official Wipeout soundtrack on CD at 15, only to discover my favorite Cold Storage tracks had been replaced with licensed music that wasn’t in the actual game.)

In retrospect, it’s clear that Wright’s music did a lot of work that Wipeout’s marketing and design couldn’t completely handle. Because the game was developed on hardware that hadn’t even been released yet, its technical limitations were formidable. The game’s music, though, is fully formed: not to mention burned into the brains of a generation of ’90s gamers.

“I love the genre now,” says Wright, who returned to the Wipeout series to contribute tracks for its follow-up Wipeout 2097. “I found a joy in creating it, and that’s why I was pretty prolific. It was only a number of weeks, and I managed to create all the music because I just got really into the vibe. It went from having no time for it to genuinely loving it.”

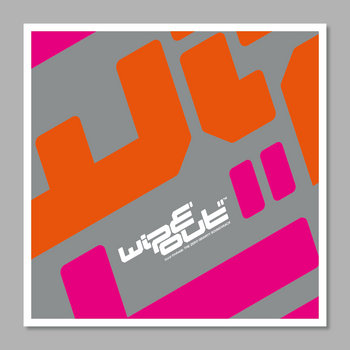

Among the music’s superfans is Albert Salinas Claret of the Barcelona-based label and agency Lapsus. Earlier this month, they released a new three-LP compilation, Wipeout: The Zero Gravity Soundtrack, on vinyl. It collects all of Wright’s original and 2097 tracks together for the first time–in fact, it’s Wright’s first-ever vinyl release–and it also features remixes by established and emerging electronic musicians from μ-Ziq and Kode9 to Datassette. The LP set is now in its second printing.

Wright’s career didn’t end with Wipeout. He created memorable soundtracks for games like Colony Wars and Tellurian Defense with Psygnosis before leaving to form Jester Interactive with his brother. If Wipeout had an impact on gamers and music fans, Jester’s first big endeavor might just have dwarfed it. The Wrights built MTV Music Generator (Music 2000 in Europe), a $50 console-based sound production tool that taught a generation of producers how to make music: Lex Luger, Skream, and Hudson Mohawke are among the artists who got their start on the software.

It’s humbling, Wright says, to have been involved in so many great projects from disparate eras of music and gaming. And yet inevitably, he finds himself at a party or a meeting, being introduced to someone new, and confronted with his true claim to fame. “I rattle off the names of a few different games” like Wipeout and Colony Wars, he says, to blank stares. “Then, with a resigned sigh, I’ll say Lemmings.”

“Oh, I fucking loved Lemmings,” they inevitably reply.

Wright laughs, and then he thinks on it for a second.

“God, I’m eternally grateful,” he says.