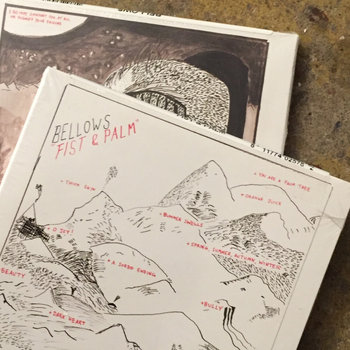

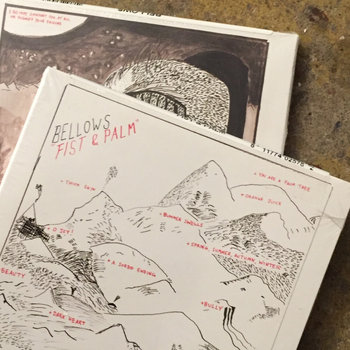

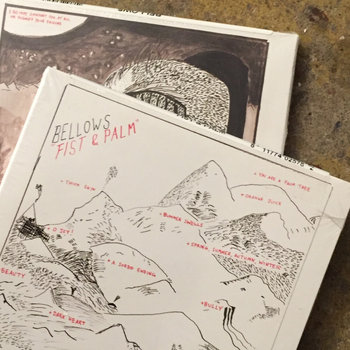

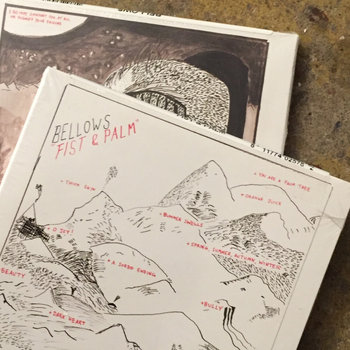

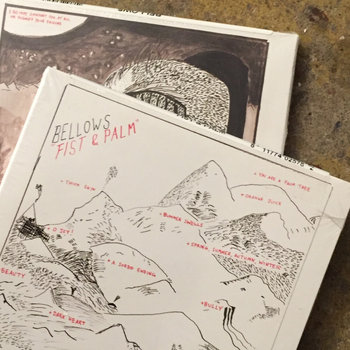

Fist & Palm, Bellows’ third album, chronicles the emotional complexities of a strained friendship at a crossroads. While some musicians may find traditional “break-up” records liberating, Brooklyn’s Oliver Kalb fosters a dialogue where heartache is examined from both perspectives, determining the steps required to find a resolution, or bracing yourself for the inevitable collapse of your relationship. With the help of hip-hop producer Jamie Wilcox, Kalb is able to tap into bouncy, whimsical drum loops and soft-focused chord progressions, honing a more solid pop structure within the evocative folk-rock balladry he’s known for. Each song is deeply personal, with piercing lyrical arrangements that tap into the tumultuous push and pull between hatred and joy in a dying relationship. This makes Kalb’s newfound pop sensibilities on Fist & Palm even more intriguing; they manage to uplift in the midst of the album’s saddest moments, striking a perfect balance between what he describes as “brutal hopelessness and the feeling of grasping for joy and transcendence at the same time.”

Compact Disc (CD)

We spoke to Oliver Kalb more in-depth about making the album, dealing with depression, and his relationship to pop music.

Your last album Blue Breath found you writing and recording in various places. What was the process like writing Fist & Palm?

I wrote the album really quickly, much more quickly than Blue Breath or As If To Say I Hate Daylight. It was basically written over the course of only two songwriting periods, separated by a year just because I had so many touring commitments in 2015. In October 2014, David Combs (of Spoonboy & The Max Levine Ensemble) asked a few dozen of his songwriter friends to participate in this challenge where we were supposed to write a song every day [that month]. It was a really difficult thing to do, especially because I had a day job at the time, but I had a really healthy schedule of waking up early, writing a song immediately before any superfluous thoughts or responsibilities got in the way of sitting down and finishing something, and then going to work right after I wrote the song. I wrote 31 songs that month, and I think seven of them ended up becoming songs on Fist & Palm, after a bunch of revisions and a lot of work. After that song-a-day challenge, I basically spent the next year on tour with Eskimeaux and my other bands, and didn’t have a lot of time to work on music at all. When I finally got back from touring in fall of 2015, the record was finished very quickly. I sort of sat down and listened to what I’d done and could kind of hear where I wanted to record to go. I wrote four more songs for the album and then brought in my friend James Wilcox, who wrote [the] electronic [components] and sequenced drum parts over a lot of the record. Jack Greenleaf mixed the record and we finished it in January of this year. It’s definitely the fastest I’ve ever made an album, and it’s also definitely my best record!

How did you manage to balance more fleshed out pop sounds and folk-rock balladry on this album?

Folk-rock balladry is definitely my instinct when it comes to writing songs—I write with an acoustic guitar, and even when the songs end up super-embellished and not at all acoustic, the acoustic guitar’s spirit finds its way into my music. It’s something I’m trying to move past! I don’t listen to much folk, or indie rock any more, so my musical touchstones when I made this record were mostly pop and hip-hop. Even though Fist & Palm is not a pop or hip-hop album obviously, those kinds of sounds (percussion, big drops, dynamic leaps, etc.) were much more inspiring to me when I wrote the record than any of the rock music I was hearing. Or not hearing, since I don’t listen to much of it. I think hip-hop is the site of a lot more innovation right now than I hear happening in rock. Why listen to a dead genre?

Would you say the pop approach on this album makes the sad moments feel somewhat uplifting and less hopeless?

Maybe. I think that pop music is interesting because, even when it’s very upbeat and dance-oriented, there’s often very dramatic and sometimes sad music hovering under the beat. One of my favorite radio pop songs from the last few years was “We Found Love” by Rihanna. It obviously has this huge drop and a kind of European club beat going on throughout the whole thing, but it’s also this totally devastating, sad song about finding love when everything else feels hopeless. That tension of the sadness of the song and celebratory feeling of the beat is amazing. I wanted to channel something like that on my record—to make a record that found a balance between real brutal hopelessness and the feeling of grasping for joy and transcendence at the same time.

Do you shy away from the “breakup song” format on this album to give your songs a better sense of what’s required in order to try and rebuild a friendship?

Yes! The album is very much about dialogue. It’s about accepting responsibility for the pain you’ve caused others, at the same time as it is about admitted that you’ve been hurt. Fist & Palm are two conditions of the same thing—a clenched fist, an open hand—they’re both the same hand. The fist is capable of hurting others and symbolizes receding into oneself and being closed off. The palm is an open hand—it’s an offering of friendship, and it’s a symbol of giving and of letting go. The record is both about aggression and generosity, and about hatred and joy. The record presents a lot of different sides of the same central issue: a strained friendship on the verge of collapse. Some songs long for collapse, some songs long for resolution. I think “break-up songs” usually have simplistic ways of looking at problems. I would never want to make a song with such a simplistic message as a traditional breakup song.

Compact Disc (CD)

What real-life sacrifices do you feel are necessary when giving second chances?

I think that self-sacrifice is sometimes important to resolving conflicts. But it’s also important to have a clear sense of who you are and what you need for conflicts to resolve in a permanent way. Being selfless is only possible when you’re centered and stable enough to be truly giving. A lot of times people think they’re being selfless when really they’re just being self-abnegating and allowing themselves to be hurt more because they won’t assert their needs. I guess you need to just listen to others but also listen to yourself.

Is it hard putting such personal emotions into words when you’re reliving these moments in your music?

It’s not hard to channel personal emotions and speak honestly, but it is hard to make difficult feelings into a product, and feel OK about delivering the story of a difficult time in my life in a bite-size way that can be easily turned into a blurb or single premiere or something. The more honest and true-to-life my songs are, the more hesitant I become to talk about them in interviews. It feels like I told this whole difficult story on my album, but have to relive these difficult moments over and over again in order to market and sell my records. My new record is about the ending of a close friendship—it’s all based on true, sad things in my life. But the conflicts I describe on my record also have resolved somewhat since finishing the album nine months ago.

I had three interviews last week, which is a lot more than I’m used to, and each of them asked something about this conflict—things like, “Do you feel weird describing fights with this friend?” [and] “Have things resolved between you two at all since making the album?” I answered those questions honestly each time, but found myself feeling yucky afterwards. Like I was somehow exploiting the truth of these events, and was exploiting the person these songs are about by delivering these interview answers in such a crass, bite-sized, marketable way. Not that I spoke in a crass way, just that the repetition of my answers in interview after interview has dulled their meaning for me. It’s a weird paradox of making confessional music: it’s almost like once the music reaches an audience, it sort of loses the privacy and intimacy that made it meaningful in the first place. I love Fist & Palm and feel no embarrassment about the album itself, but something about the whole music industry roll-out interview aspect of it, testifying about this difficult subject over and over again, is really weird.

How important is it to push through depression and mental health stuff when you’re trying to finish a record like this?

Over the past year or so, I’ve struggled with anxiety and depression. I had my first anxiety attack last summer — I didn’t know what it was at the time, but it manifested almost like a punch in my stomach. I couldn’t catch my breath, couldn’t really talk to my bandmates, super accelerated heart rate, dull ache in my gut. It’s happened a few times since. Even though Fist & Palm is sort of about anxiety and depression (or at least those problems exist under the surface of the narrative), I mostly found myself recording it in times of lucidity and relatively stable mental health. I think that in times of crippling anxiety and depression, it can be impossible to make art. I know that in the worst times of my problems with anxiety, it’s incredibly hard for me to even interact with people in a normal way, much less make interesting, complicated music. I don’t think it’s healthy to expect that a person can simply push through mental health issues and make amazing illuminating art. Sometimes, the problems are just so overwhelming that the basic faculties required for creativity are denied you. Music can be a great therapeutic tool, but it also shouldn’t be seen as a failure if depression makes it impossible to get to the point where your music can speak to you in the way that a therapist or friend would be able to. I found it very rewarding to finish my record, but it didn’t solve any problems in my life.

What was it like finding yourself in New York after moving around a bit after you graduated?

I had a really eye-opening experience when I moved back to New York after living in Chicago for a little while—I suddenly understood what a strong connection I had to the city and decided that I really never want to leave again. I grew up in New York and I have a really deep, nostalgic love for the place. The feeling of getting lost walking around, or the feeling that you could move around the city for days and weeks and never run into anyone you know (unless you are walking around Bushwick)—these were things that had been really missing from my life when I didn’t live here. It’s possible to feel totally anonymous in New York City. The feeling of anonymity has played a big role in how I write songs: to be able to walk around so freely, just getting lost among a ton of people in my neighborhood while I listen to my demos. Something about the constant motion and the fact that no one stops me, that I don’t know any of the people I see, and I don’t have to interact with anyone, but am still somehow with all of these anonymous people on the street and living among their bodies—something about that feeling motivates me creatively. I feel more creatively motivated taking walks in Brooklyn than I have in any other place I’ve lived. I love that feeling.

Compact Disc (CD)

A personal moment at Palisades was the inspiration behind “Orange Juice.” What spaces in New York make you the feel the most comfortable being a musician?

Palisades was cool because they were very welcoming to touring bands who have never played in New York before. It’s great when DIY venues aren’t so money-conscious and are willing to give newcomers a chance. Palisades shut down this year, and Aviv might be shutting down, too, so there are really only a handful of all-ages DIY venues left in New York. That’s terrible, especially because Palisades and Aviv were so democratic and non-hype-oriented in their booking practices. I love Shea Stadium—it’s where I’m doing my record release show—and I love Silent Barn. I hope they can both stay open forever. We need to protect those spaces! It’s so easy for venues like that to shut down for sad reasons. The NYPD really jump at an opportunity to do a sudden inspection and just ruin everything. People don’t realize how many people have to be involved to keep an all-ages DIY venue running. They need a lot of selfless people and a lot of volunteers. If you’re reading this, please consider volunteering at a local DIY venue!

How important is it for you to work with smaller labels and collectives who share similar visions and intentions in terms of community building and music business?

I think the most important thing to consider in choosing a label is whether the label is run by people you trust and who respect your art. I don’t think that bands should feel pressure to never sign with a bigger label just because the of some puritanical DIY ethos—but I have had a lot of friends get sort of screwed over by bigger labels who seem friendly at first, but then when “hype” becomes a factor, the label suddenly wants to make creative decisions for the band and make weird marketing moves that just end up sapping the original creative spirit and idea that made them sign that band in the first place. I’m very wary of multiple album contracts, and of big monetary advances that have to recoup endlessly before the band can be paid or freed from their contract. I think if you can have a face-to-face conversation with your label about what they expect from you and what you expect from them it’s a very beautiful thing, especially if the conversation is based on a shared love of the album you’re putting out together. Double Double Whammy are definitely a very trustworthy, non-evil label. I love working with them a lot, and they’ve done really great work with all three of my bands’ records at this point (Bellows, Eskimeaux & Told Slant).

Can you talk about your upcoming tour with PWR BTTM?

I went to college with Ben and Liv from PWR BTTM and I feel a big connection to their band through being fellow Hudson Valley people and having gone to Bard together. The music scene at Bard, where both of our bands went to college, was really supportive and I think of Bellows as having been formed in a big way by Bard and the Hudson Valley as a space. It’ll be great touring with PWR BTTM and just reviving some of the positive energy that we had in the show spaces we both contributed to in school.

What have you added to your live set-up ? Are you bringing anyone from THE EPOCH on tour?

We’re actually just preparing for our record release show and fall tour right now, and trying to come up with ways of interpreting Fist and Palm with the limitations of the four-piece band set-up. I think this record is particularly not suited for a rock band arrangement, so we’ve been talking about incorporating sample pads and SP-404 samplers into the arrangements to try to recreate some of the exact sounds on the album and not just “rock-ify” everything, which has been our instinct with past Bellows albums. I think of Fist & Palm as a lot more of a pop record than a rock record and it’ll be a fun challenge to try to orient the live band to play the songs in a way that’s true to the recordings. As far as the tour goes, it’s just the usual band—Felix Walworth (of Told Slant), Gabby Smith (Eskimeaux), Henry Crawford (Small Wonder) and we sometimes tour with Jonnie Baker from Florist.

—Max Mohenu