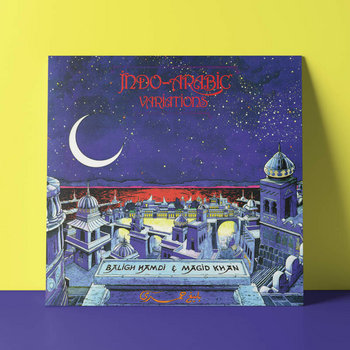

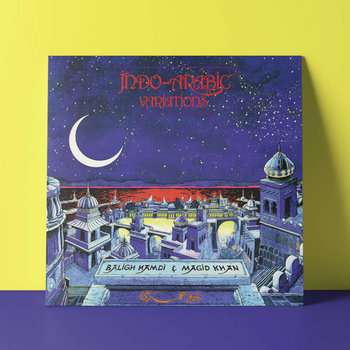

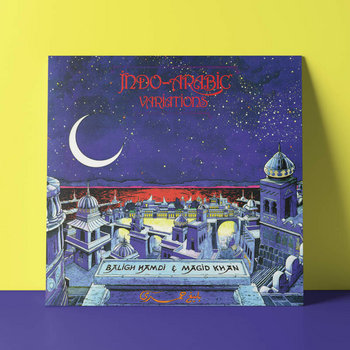

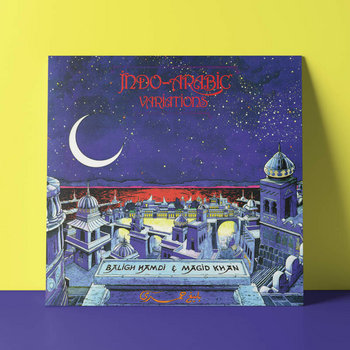

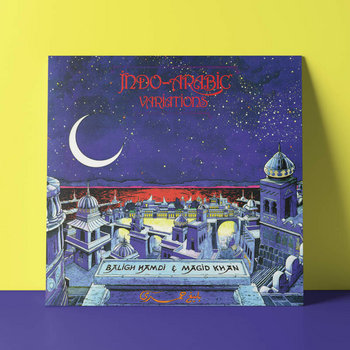

Baligh Hamdi was one of the most prolific and successful composers in modern-day Egypt, helping to usher in a new cosmopolitan age in Cairo and beyond in the 1960s and ’70s. In the liner notes to his recently re-released 1980 album Indo Arabic Variations on Altercat, Hamdi is quoted as living by one rule in his music: “Draw from the local tradition to reach the world.”

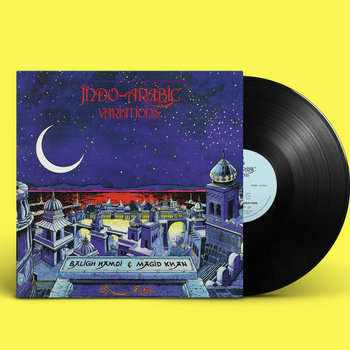

Vinyl LP

In the mid-1950s, Hamdi began composing for popular Egyptian singers, drawing upon traditional folk melodies and rhythms and adding luscious string arrangements for a decidedly classical sound. “Baligh’s brilliance is associated with our cultural calendar,” says Tamer Hamdi, Baligh’s nephew, speaking over the phone from Cairo, Egypt. “His sounds are what people listen to here. They are the most famous songs ever created in Egypt.”

These sounds would most knowingly proliferate Western culture in the form of samples utilized by Jay Z, who controversially borrowed Abdel Halim Hafez’s “Khosara Khosara” in “Big Pimpin”; Earl Sweatshirt, who used Umm Kulthum’s “1001 Nights” in “EAST”; Madonna and Aaliyah, who sampled Warda (whom Baligh was married to for ten years); and many others.

The relevancy of these cross-cultural transmissions from East to West in the 2000s is that it was also Hamdi who pioneered similar transmissions, but in reverse, from West to East, many decades before. In the ’60s and ’70s, he began experimenting with Western instrumentation in his music, writing for saxophone, guitar, drumkit, moog synthesizer, and many others heard throughout the essential compilation Instrumental Modal Pop of 1970’s Egypt, released by Sublime Frequencies in 2021. The sounds produced are Eastern-tinged psychedelic jazz, pop, and rock; equally as appealing to fans of the Sun Ra Arkestra as they are to fans of Dick Dale and the Del Tones—a far cry from Hamdi’s earlier orchestral output.

“If we are talking about the concept of merging two civilizations, Baligh was before the trend,” says Tamer Hamdi. “He did it before Peter Gabriel, before Led Zeppelin, before Buddha Bar. He was a visionary.”

In the late 1970s, and in the spirit of constant progression and innovation that had defined his career up until this point, Hamdi turned his attention Eastward to India, and in particular, toward the majestic sounds of Magid Khan: a well-known sitar player at the time, who came from a rich lineage of musicians. On the occasion of Khan’s visit to Cairo in 1979, Hamdi rearranged some of his own compositions to feature the sitar player as a prominent soloist in a body of work he named the Indo-Arabic Variations.

Unlike West-meets-East collaborations, which merge vastly different tonal and harmonic understandings of music alongside one another, this East-meets-East collaboration features more subtle disparities. With Indian and Egyptian music both utilizing similar modal scales (the Indian raga and the Arabic maqam), monophonic textures, and an equal emphasis on quarter tones, a main point of difference lies in the timbre of the respective countries’s instrumentation. On Indo-Arabic Variations, the sitar and tabla, pillars of Indian music, comfortably coexist alongside the qanun, arghul, and ney of Egypt and the Middle East.

Vinyl LP

The resulting output is a beautifully melodic and heavily percussive orchestral album featuring half a dozen hand-picked soloists improvising over centuries-old modal systems from the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia. It’s a unique conversation between ancient styles flirting with an essence of regional familiarity. The interplay between soloists adds an element of surprise to each track on the album, as disparate melodies fade in, out, and on top of one another, causing a murky tonal center. Hamdi sets real-time parameters for the instrumentalists to take their turn at soloing. They roam far, wide, and free, albeit at the constant whim of the maestro’s watchful baton. A few years later, in New York City, experimental jazz musician Butch Morris would coin this technique “conduction.”

For Sergi Roig, label head at Altercat and a collector of Arabic music, the Indo Arabic Variations album cover is what initially caught his attention on a recent trip to Egypt. Upon first listen, Hamdi’s international influences were instantly recognizable. “When you hear 200 songs and your ear is not as accustomed [to Arabic music], they can start to sound the same,” he says of his own listening habits. “But when you hear [those sounds] mixed with jazz, you immediately think “Wow, what is that?” I don’t recall any other easily digestible music that fuses Arabic, Indian, and jazz.”

Although recorded in Cairo, Indo-Arabic Variations was released exclusively in France, where a large diaspora from the North African Arabic community resided. Hamdi had spent a lot of time in France, and ended up living there in exile for a number of years in the 1980s following a controversy in Egypt. Asked about his broader contribution to the cultural canon, Tamer Hamdi offered the following: “Art has to be put in the perspective of time. Time and history are the artist’s enemy. Van Gogh won time, Beethoven won time, and Baligh Hamdi won time. Fifty to sixty years later and you still hear his music on the radio all throughout Egypt. This is winning time.”