Photo by Abney Park Chris Almeida

Photo by Abney Park Chris Almeida

When Gus Fairbairn was in high school, decades before he adopted the moniker Alabaster dePlume, his German teacher pointed at a calculator during a test and asked for the translation. Fumble as he might for the correct answer that day in North Manchester, England, he had nothing but silence to offer.

“I don’t remember the teacher’s name, but I do remember the German word for calculator: tasch-en-rech-ner,” dePlume, now 41, says with a laugh, sounding out the syllables with the diligence of someone who has indeed spent the past quarter-century dwelling on this tiny teenage mistake. “I felt shame. We hold on to lots of things when we feel shame.”

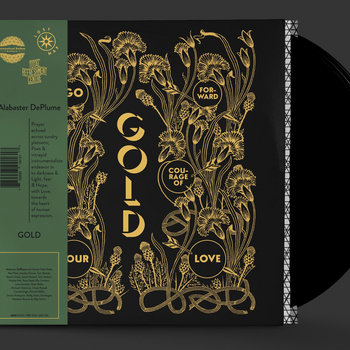

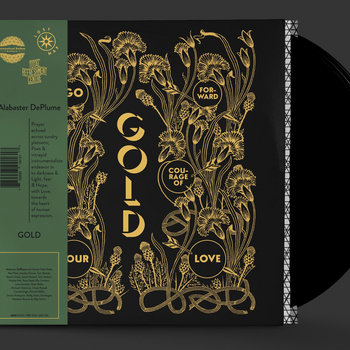

2 x Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

In his warm Mancunian lilt, dePlume also recites the German word for calculator during “Don’t Forget You’re Precious,” the motivational wonder near the start of his musically sprawling and personally affirming new album, Gold—Go Forward in the Courage of Your Love. He presents it not as some point of educational pride but instead as a note to self: the mistakes and minutiae you carry around for life, like an ex’s email address or an adolescent embarrassment, matter less than who you are now and what you can become. “They can’t beat us if we don’t forget,” the poet, saxophonist, singer, and bar-side philosopher warbles over a lush bed of pensive horns and strings and playful synths. “They can’t use us on one another if we don’t forget we’re precious.”

DePlume recorded the 19-track Gold over the course of several weeks at London’s Total Refreshment Centre, the low-rent and high-reward creative hub of which he’s been a linchpin for six years. He built new bands daily from a rotating cast of 21 musicians, asking them to play a set of motifs and melodies they’d barely heard, let alone rehearsed, to a click-track. After creating a graphic illustration of the results on a massive scroll of white paper, he stitched together a 70-minute edit from all those sessions, weaving between versions of the same songs like a mashup master.

“I don’t actually know if it’s finished,” says dePlume four days before Gold’s release on Chicago jazz bastion International Anthem, speaking from the apartment of label head Scott McNiece. “Is a work of art ever complete? But everything in my life has pointed in some small life to this record.”

Indeed, the process of making Gold hinged on skills and enthusiasms dePlume has developed over his lifetime. “I had to grow, and choose courage and love to make it,” he writes in the liner notes. A former teaching assistant, dePlume once worked at a Manchester charity that cared for adults with learning disabilities. He led the music program there, sometimes guiding joyous improvisational sessions with an impromptu orchestra of 30. Some of their melodies served as fodder for the instrumentals of the halcyon To Cy & Lee: Instrumentals, Vol. 1, his breakthrough 2020 debut for International Anthem that came after a decade of releasing albums.

Following a move to London, a gig at Total Refreshment Centre prompted a residency that involved a monthly concert. He initially balked at the invitation, worried that his ambition to write new music for each show would interfere with his day job and wear him out. He recruited new bands for every set so that they could catalyze his work.

“I had to connect to different communities and bring them together—which is what I want to do, anyway, bring people together,” he says. “I was scared of it, because I didn’t have the time. But I had to go towards the fear.”

dePlume often compares fear to encountering a ghost—you can run away, but the ghost will surely follow; or you can wait for the ghost, let it pass by, and then move on with your life. “I want to go towards the fear,” he continues. “How else do I know what fear says?”

In a way, Gold itself is an act of going towards this fear. Cy & Lee omitted the sociopolitical poetry of dePlume’s past works in hopes of offering an easygoing entryway for newcomers. It worked, earning legions of new listeners including Bon Iver who sampled “Visit Croatia” after being introduced to his music by Drew Christopherson. But Gold is a more robust and complete manifestation of dePlume’s vision, his poetry and playing coiling in continual motion. And when International Anthem encouraged him to turn it into a double LP, he again balked, anxious it would feel too pretentious. A friend reminded him, however, that The Clash’s London Calling had been a double LP; now that was a lead he agreed he could follow.

It is tempting to label dePlume as some facile New-Age jazzer obsessed with talking about love and solidarity or a self-hope guru playing saxophone out of the side of his mouth before offering up another inspirational mantra. There’s more to Gold and to dePlume on both counts. DePlume’s saxophone lines, for instance, have an uncanny ease, with the graceful lead of opener “A Gente Acaba” unfurling like a slow spring breeze. And his musical zone is notably ecumenical, as he zigs and zags from spiritual jazz to no-wave bedlam, from blissed-out dub to twilit ballads.

Working with so many musicians and letting in so many sounds was another opportunity to overcome fear, or to get over any sounds that didn’t immediately strike him as right. “When players come and there is a difference in sound to what I expected—which is always, by the way—I love it,” dePlume says. “It is what I asked, so how can I do anything but celebrate it? Sometimes that can be challenging it, but I love it.”

2 x Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

And despite pleas to remember that you’re precious or dePlume’s promise at one point that “I will not be safe/ I will be magical,” Gold is laced with bouts of self-doubt and darkness. During “Broken Like,” a seesaw between the propulsive and the pensive, dePlume details ways we’re all obsolete and injured. “Now (Stars Are Lit),” however gorgeous, wallows, its squelching electronics and muted horns suggesting a mind that just won’t start. To overcome an obstacle, dePlume suggests, you have to acknowledge it—how can you remember you’re precious, after all, if you don’t forget in the first place?

“Those feelings are all part of me, all a part of our experience of this world. If I am going to make choices that bring me pain, I am still going to celebrate my choices in leading my life,” he says. “We’re not going to bring peace to this world by saying, ‘Let’s not talk about nasty things.’”

On a recent Sunday, dePlume played the opening set of the final day of the Big Ears festival in Knoxville, Tennessee. The faces in the room betrayed the hangdog exhaustion of people who had spent three days experiencing an immersive world of free jazz, experimental electronic, and psychedelic pop. But just after noon, the towering dePlume bounded on stage in jeans so baggy he looked like the mere suggestion of a skeleton, glowing from behind his scraggly brown beard.

“I don’t know if you can tell,” he greeted the capacity crowd, “but I love my life.” He jumped up and down repeatedly, waving his red-gloved hands. The room’s energy instantly shifted, every hangover lifting.

The trumpeter Jaimie Branch and her versatile band Fly or Die had trailed dePlume onto the gear-clotted stage, set to perform with him for the first time ever in that moment. He had met briefly with Branch and bassist Jason Ajemian a day earlier, showing them a few melodies and tunes he might want to play. Every few minutes onstage, he would hum a few bars or suggest a key, and the band would dig in, motivated by the possibility of what might come next. “If in doubt, yes,” dePlume told both band and crowd, everyone laughing though it was clear he fully meant and embodied this axiom.

As they worked through a half-dozen tunes, the band seemed to surprise itself, as if the tunes had allowed them to go somewhere they never expected to visit. dePlume read bits of text he’d collected for three days at an art installation he calls “Confusion Desk,” where he invites anyone to share anything, a mutual lesson in radical vulnerability. There were birthday wishes, pleas for world peace, and bits of life advice like “Come with fierce grace.” Everyone smiled at that note, pondering the sudden insight. “That’s a good one, isn’t it?” dePlume beamed, a benevolent Cheshire cat.

It all felt like a nondenominational communion, a word at which dePlume bristled slightly a few days later for its cult-like connotations. But everyone seemed vulnerable and open, the barrier between audience and performer interrupted by a communal intrigue: What might happen next? “Have you come to my gig and forgotten that you’re precious?” he quipped at one point. If they had, no one seemed to leave that way.

That’s the trick that animates Gold and, it seems, dePlume’s status as one of modern jazz’s great new facilitators of exploration. “Technically, I’m just the entertainment,” dePlume says, chuckling. “But we’re not decorating. I used to think it was sad when people would see music as decorative, but these days I think it’s dangerous, an attack. We are working on something real.”