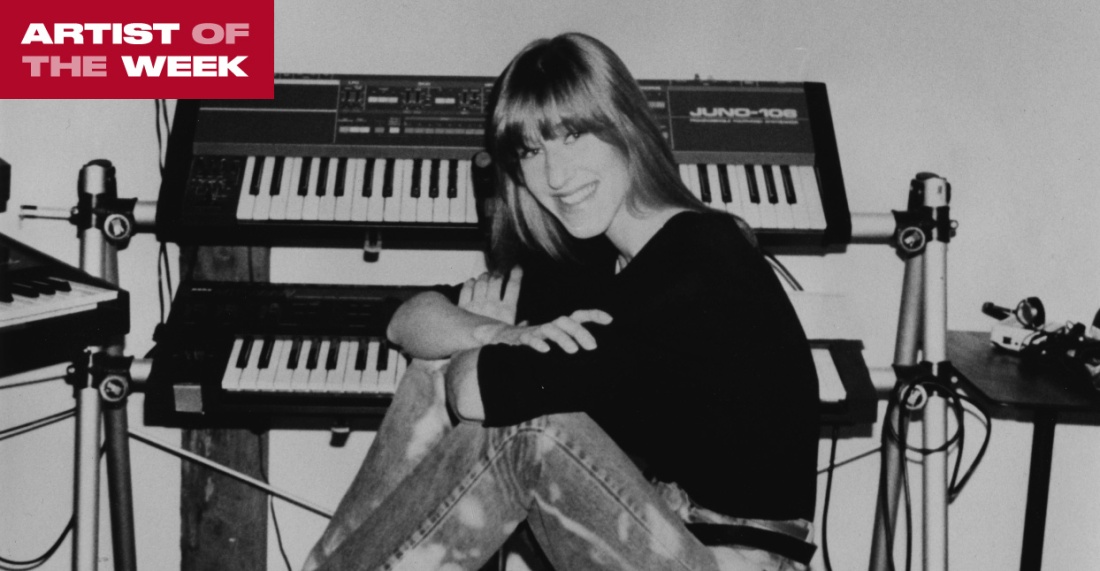

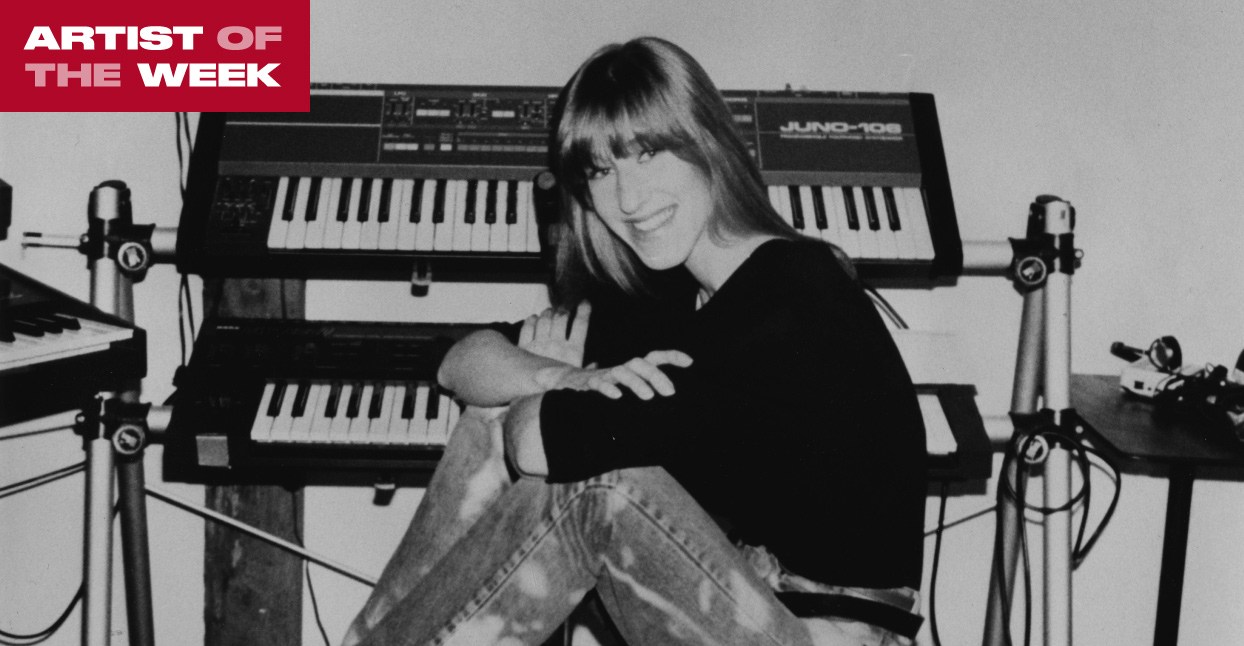

Happy Rhodes’s music first reached me in 1992 or thereabouts; I’d been on early Internet mailing lists dedicated to Tori Amos and Kate Bush, and contributors there led me to Ecto, the list for fans of Rhodes’s work. I special ordered a couple of her CDs—there was no way to sample any of these songs, after all—and when they arrived in a few weeks, probably hand-mailed from Kevin Bartlett of Aural Gratification in upstate New York, they did not disappoint. Rhodes’s work is transportive art-pop built around elegant fingerpicked guitar and synth layers that shift between gauzy hum and opaque buzz—and, of course, her voice. With a four-octave span, she can easily shift from rich contralto to airy soprano, and she creates dizzying studio harmonies with multiple parts, all performed by herself. Her lyrics are imaginative, drawing from myth and literature as much as they do personal experience, and there’s a vein of strong emotion to them—sometimes strength and hope, sometimes anger, sometimes a wild sort of sadness, sometimes a measured one.

When I first heard Rhodes’s music, I was a lonely, odd kid about to enter high school—bright, but troubled, involved with people and drugs who were both very bad for me, and generally less interested in school than I was music. My experiences didn’t match up with most of my peers, and I kept the worst of them hidden for longer than I should have. I was also starting to get really into hardcore and punk, going to Positive Force and Riot Grrrl meetings, and the things that spoke to me about that scene also spoke to me about the art-pop singer-songwriters I loved, though the music seemed 180 degrees aligned. This was all music for misfits; punk externalized, where art-pop turned strange and internal. I had no real concept of where Rhodes’s music came from at the time; turns out that my teenage instinct had honed right in on a similar spirit. “I was forced to live in my own world, in my own head,” says Rhodes of her childhood. “I was an extremely quiet child in my home—that’s not to say I was not outgoing, I was outgoing enough. I liked to be funny and I liked to have fun when I was outside of the home. When I was inside of the home, I was like a mouse, I didn’t make a peep. It was mostly because I don’t think I ever felt safe, so I retreated a lot and I had to learn how to rely on myself and only myself.”

Rhodes’s mother, Susan Stamper, was a dancer who’d trained with the New York City Ballet; her father, Vernon Rhodes Jr., was a visual artist. Art, and expression, was in her blood, and though her parents divorced early on in her life, Rhodes took inspiration from both of them. She was an outcast at school; like me, she just didn’t fit. “I felt sorry for myself; I was angry; I was resentful; I felt deprived,” she says. “There was a deep sadness in me that drove a lot of my music, and also, just a desire to not be the same, and I was inspired by other music that was quite like that. One of the reasons Kate Bush inspired me, who I didn’t hear until I was probably 14 years old [on Saturday Night Live]—the reason she inspired me was because she was so damn weird.”

Rhodes had been given a guitar by her mother for her 11th birthday, in 1976; she’d always known she was going to make art, but she’d never felt a particular affinity for the instrument. “Immediately I adopted this philosophy of ‘make it my own’,” she says of developing her fingerpicking style. “I don’t know where that came from, but there was a music teacher in my school at that time who was giving after-school guitar lessons, acoustic guitar folk lessons… I think I took one class with a bunch of other people, of course, and her whole thing was strumming—‘That’s what you do on a folk guitar, you strum it, and this is how you strum.’ Those were the lessons, and my immediate reaction to that was ‘Why? Why does it have to be that?’” Rhodes fingerpicked “Silent Night” at a school talent show—and, despite her unpopularity, won.

This very punk attitude didn’t lead her to the style itself, as it well could have; Rhodes loved the baroque, the complex, the multi-layered and carefully crafted in music. She loved Wendy Carlos. She loved Queen. She loved Genesis, Yes, and David Bowie. Her love of both Bush and Freddie Mercury encouraged her to experiment with her voice, pushing her natural alto to its fullest limit. Music absorbed her; finding school an untenable environment, she dropped out in 11th grade and started trying to make her way in the world as an artist. This brought her to Cathedral Studios in Rensselaer, New York, to Pat Tessitore and Kevin Bartlett. She walked in with the intention of becoming an engineer, learning at Tessitore’s hand; that goal changed pretty quickly.

“[Tessitore] said, ‘You’re a singer, right? Let’s get you in the vocal booth and you bring your guitar, play something. I’ll put it down on tape, and we’ll start from there’ and I did that,” she says. “And I came back out, and he said, ‘Well, I got news for you—you’re not gonna be an engineer, you’re gonna be a singer.’”

These early recordings Tessitore made with Rhodes, which were recorded and released on Bartlett’s label from 1984-1986, are the focus of the new Numero Group collection Ectotrophia, and they’re an excellent introduction to her work for those unfamiliar, and a reminder of what’s so thrilling about her for those of us who have loved that work for a long time. (The Ectophiles have supported Rhodes through the decades, a small but passionate following, even putting on Ectofest events on both coasts.) Many of my high school mixtape favorites are here: “Come Here,” which sounds like an intimate transmission from an alien dimension, and “If So,” which sounds like it’s touching a raw heartstring with the tip of a melancholic claw, and “Because I Learn,” a statement of steely determination bricked up with synths.

Rhodes drew the cover art for many of these early recordings (Rhodes I, Rhodes II, and Ecto)—Ecto was the first I owned, and I was always fascinated by the fact that these beautiful, delicate records featured such toothy, skeletal monsters on the cover. (You might think at first glance that they’re metal albums.) “My father used to tell me all the time, ‘There is nothing that you could create from your own brain, from your subconscious, there’s nothing that you could create that would be bad, it’s all good,’” she says when asked about these creatures and their place in her creative universe. “I thought that was really lovely and freeing, ’cause that implies that we are innately all good, and I like that notion.”

Compact Disc (CD)

“Even if you’re a visual artist and you create dark imagery, it doesn’t mean you’re a dark person,” she continues. “I certainly am not a dark person, but that was very freeing… so I would always try to make really scary things and just test that theory. If these really strange, scary things can come out of me, should that scare me? I was never for a moment scared. Each monster I would try to make scarier and scarier, [with] sharper teeth and crazier eyes, and very skeletal, and claws. You’ll notice I never did make cute, round, Jello-like monsters.”

Rhodes’s music is often haunting, too, but it thrums with persistence, with determination, with love. “I Am A Legend,” which appears on Ectotrophia, is a bit of a love song to herself—at the time, she was trying to convince herself that her songs were worth hearing (“I am a legend in my own mind”); “Feed the Fire,” from 1991’s War Paint, offers the thought that “My ears are lucky to hear / These glorious songs / Of inspiration / And voices crafted from thunder / The power of life.” “It’s like my album [1993’s] Equipoise, which means equal balance, roughly,” she says of her music. “It’s all about light and dark. That’s why one half of me is my face and one half is a monster face, albeit it’s not a very scary monster… but still, we all have monster in us and it’s not a bad thing. You need it, we all need a balance of light and dark. It’s not good and bad, it’s just this and that.”

During our interview, when I mention to Rhodes how much her music particularly meant to me as a fellow outsider teen, she offers me a piece of particularly salient advice. “Spend the rest of your life just letting yourself be a kid, because that will really help,” she says. “I mean, we don’t need to hold onto the anger for our entire lives. The anger and the resentment, they’re not helpful, really, but allowing yourself to be a kid—I mean to be goofy as hell—that is extremely healing.” It’s great advice, and it makes something clear to me that wasn’t when I first heard Rhodes’s music—it is all in the service of healing, in doing one of the best things art can do, pulling the threads of beauty from pain.