When Kamaal Williams first started recording The Return, his first full album under that name (he’s also known as Henry Wu), he knew the bar was incredibly high. Williams was the keyboardist in Yussef Kamaal, a duo with drummer Yussef Dayes that exploded out of London and made waves around the globe with their 2016 album Black Focus, which fused jazz with electronic dance, creating a crossover path between those scenes in the United Kingdom.

Then, a year ago this week—and one week after the 2017 Jazz FM Awards had crowned them the year’s Breakthrough Act—Yussef Kamaal dissolved as suddenly as they had arrived. “A lot of people were writing me off,” says Williams. “People were saying, ‘Has he got it, man? Can he come back and do it again?’”

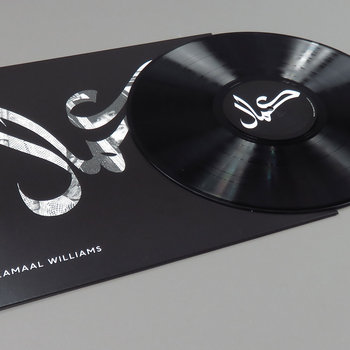

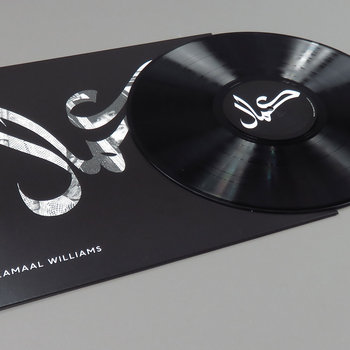

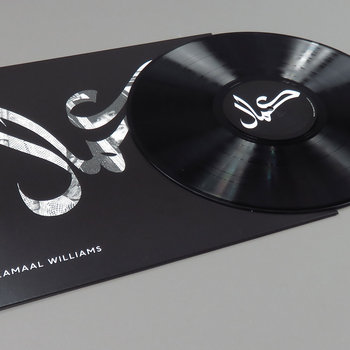

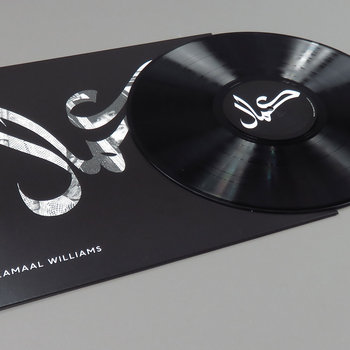

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

The Return picks up the gauntlet thrown down by Black Focus. It focuses on pure groove, augmented with loop-like repeated motifs but achieves them with live drums, funk-driven bass, and smooth, twinkling Fender Rhodes lines. It’s a clear continuation of the sound that earned Yussef Kamaal their reputation as the new vanguard of jazz fusion.

Williams, however, doesn’t feel comfortable with that label. “I wouldn’t call it jazz fusion,” he says. “I wouldn’t even call it jazz, to be honest.” He doesn’t call it EDM, either—or dance music, club music, hip-hop, or even funk. The one label he does apply is the one he used in his March Facebook post announcing the album’s release: “the essence of the London Underground.”

“When I say that, I mean that I think it’s just undeniably London,” he explains. “The four of us who make up the album, we’re all from a different part of London.”

As such, each musician is also rooted in a different music scene. Bassist Pete Martin grew up on the reggae, dub, and funk of 1970s North London; drummer Josh McKenzie, known as MckNasty, was nourished on gospel music in central London; engineer Richard Samuels, from West London, cut his teeth on broken beat and soulful house music; and Williams hails from the grime and garage scene also of West London. Each of these strains derive in some way from jazz, and are now integral to the current London jazz scene. But the band members’ respective pedigrees make them at best tangential to that scene, and resistant to any attempt to fit them nicely into one slot.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

There is one aspect of their music, though, that bears the clear influence of jazz: everything is improvised. “There’s no plan, as such,” says Williams. “There are ideas, and there are feelings, and there are grooves, but there are no plans. I’ll have a seed that I plant in the group and it grows by itself.”

The seed he plants usually takes the form of a rough, basic idea: a motif, a beat, a timbre, or a combination of the above. The band starts there, enters the studio (“When I say studio, it’s my mum’s kitchen in Peckham, South London”) to play. “We’re improvising with groove. We’re improvising rhythmically,” he says. “It’s not what you’d think of in a traditional sense of a saxophone player or a keys player soloing over the top of a groove. The rhythmic exchange between the three of us is where the improvisation is.”

The jams can go on for 20 minutes. When they’ve finished recording, they review it and pick out what they like. “We would listen through, and we would go, ‘Right! That bit there, from minute 12 to minute 18, that’s a tune!’” says Williams. “Or, ‘Oh wow, that bit sounded amazing, let’s take that bit out and put it with this bit over here.’ That’s the most natural way to do it, and we like to keep it natural.”

The music on The Return is too cunningly designed to suggest cut-out fragments or sound collages, however. It flows organically. “Broken Theme” bursts into being with a simple lick from Williams and MckNasty; Martin enters with a slippery bass figure, followed by Williams adding a secondary vamp and MckNasty extending his line; thus, layers of complexity are added one by one. “Medina” opens on a musing electric piano introduction with a few streaks of bass running through it, then settles into a trancelike 3/4 rhythm with Williams developing melodic motifs on top.

After recording these improvisations, Williams and engineer Samuels spent six months editing, processing, and refining the music to get the sound they wanted. (The drum sound alone, which they wanted to “really bang,” took weeks.) It’s for this reason that Williams regards Samuels as a member of the band: “He’s my right-hand man.”

If The Return refers to Williams’s phoenix-like resurrection from the ashes of Yussef Kamaal, it also signifies other returns: to his childhood home, to the genres that first inspired him and his bandmates, to an intuitive music-making process that is also, he says, nearly telepathic. “We very much let the music almost play itself. That’s the spiritual aspect—all of us have a spiritual connection, and we use it. The whole album is a dialogue between the three of us. We’re not just three musicians that have been put together for the sake of making an album. We understand each other’s souls, musically, and that’s why the connection is so special.”