The infectious rhythm known as Makossa was once the heartbeat of Cameroon, and dominated the streets and radio stations throughout Central and West Africa. Translated as “(I) dance” in the Douala language, spoken across Cameroon’s coastal regions where the genre formed, Makossa was very much at the heart of the country’s post-independence musical pride.

Names like Nelle Eyoum and his band Los Calvinos wrote the Makossa rule book beginning in the early ‘60s, declaring that any genre, instrument, or style could only add to Makossa’s musical flavor. Then, driven forward by Makossa’s “second wave” by artists like Francis Bebey, Eboa Lotin, and Jean Dikoto Mandengue, the genre began edging into the Cameroonian mainstream and, eventually, abroad. In 1972, a chance record store discovery of Cameroonian jazz pioneer Manu Dibango by New York icon David Mancuso brought Makossa to downtown disco through his biggest hit in Soul Makossa. James Brown caught the bug too, taking influence from (and arguably plagiarizing) André-Marie Tala’s Hot Koki on his 1973 single “Hustle (Dead On It).” Tala subsequently sued Brown, and won.

Makossa was a melting pot of influences from across the African continent and beyond—the biggest musical impact came from the Congo. In the 2005 publication Africa’s Media: Democracy and the Politics of Belonging, author Francis B. Nyamnjoh spoke of how Congolese rumba initially reached Cameroonian shores through Radio Léopoldville’s powerful transmitters from what is known today as Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Other major influences were merengue from the Dominican Republic, the energetic tropical inclinations of Ghanaian and Nigerian high-life, and the traditional form of Cameroonian guitar music Assiko. These opposing forces all came together in the urban corners of the country in cities like Edéa and Douala.

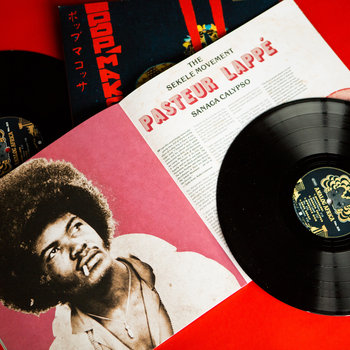

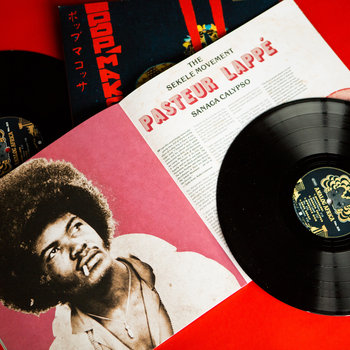

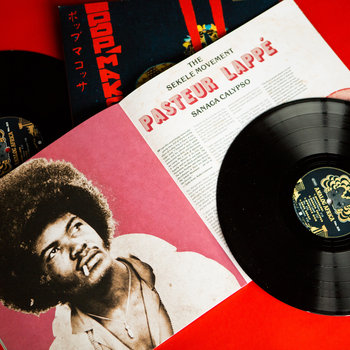

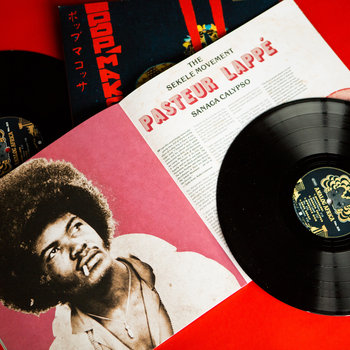

In the new compilation, Pop Makossa – The Invasive Dance Beat of Cameroon 1976 – 1984, Analog Africa celebrates the prime years of beachfront grooves by showcasing the tracks that kept Cameroon bumping throughout the decades.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Since 2001, Samy Ben Redjeb, founder of Analog Africa, has scoured the African nation in search of its long-forgotten hidden gems. Pop Makossa was nine years in the making. “I started the project in 2009 when I went to Cameroon, but the record needed to brew like a fine wine,” says Redjeb, who compiled the album.

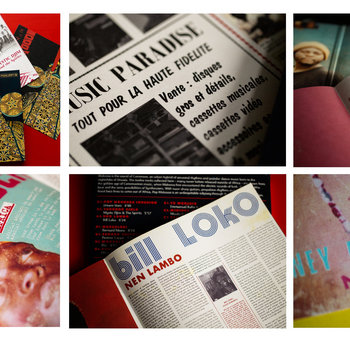

“For this record we managed to find around half of the people in Cameroon, and the rest of them were in Europe, mostly in France. Generally, finding the artists wasn’t so complicated,” says Redjeb. He makes the act of tracking down forgotten names sound far too easy. “One musician takes you to the next, and where there is a will there is a way. Finding the music is not the most difficult part,” he continues. “A picture of a musician can be as exciting to me as finding the music itself. You meet the people, you hear the stories, and it gives you a totally different level of appreciation for the music itself. To me, it all belongs in the same world.”

Like many nations in Africa fighting for independence from the colonial powers (France, in this case) after World War II, Cameroon’s population began to take pride in their culture and heritage throughout the 1950s. Music genres popularized during this time—such as Bikutsi, a more modern form of fast-tempoed balafon music defined by artists like Messi Me Nkonda Martin—and became sources of pride and identity in a rapidly-changing Cameroonian society (the country’s soccer team also heavily contributed to unifying the nation).

“Makossa became a word of reference,” says Redjeb. “People may not have known what it was, but when they heard the word, they were curious to find out more. Most of the African countries have a vibrant music scene, but Makossa was very catchy. It was pop music mixed with modern forms, so it had a much broader appeal than other styles from across Africa. Bikutsi, for example, is very rooted in tradition. So it was big in Cameroon, but never expanded outside of the country. Makossa had traditional elements, but it was modern, and Makossa could absorb everything from disco to music of old. That’s why it spread like wildfire throughout West Africa.”

When the country gained independence on January 1, 1960, drinking spots and venues flourished, the cities started to modernize, electricity became widespread, and new musical instruments (often imported) became easier to get a hold of. With their newfound freedom, Cameroon became a melting pot of different cultures and musical infatuations, and with that increased interest from people on the street over the next decade—Makossa would become Cameroon’s greatest musical export.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Homegrown labels like Disques Cousin and Africa Oumba kept Cameroon dancing, and names like Nkotti François, Ashiko De Luxe, and Namy Jean Deboulon became national sensations throughout the ‘80s. Eko Roosevelt, whose 1980 recording “M’ongele M’am” is a particular Pop Makossa standout, became one of Cameroon’s most successful and idolized musicians. Disco-influenced classics like “Kilimandjaro My Home” and “Ndolo Embe Mulema” are still peak-time radio hits across Central and West Africa to this day.

In addition to being a renowned musician, Roosevelt is also known by a different title, “His Majesty,” and not simply because to some he is considered Cameroon’s Prince. Kribi, a port town formed of palm trees and white beaches in Cameroon’s southern province, is where Roosevelt gained the hereditary role of village chief. “I arrived in Kribi to attend a funeral, and after the ceremony I was surrounded by the traditional leaders who asked me to replace my grandfather as village chief,” Roosevelt says in an excerpt from the Pop Makossa liner notes. “I didn’t want to leave music, but I loved the idea of helping my community. I thought to myself, ‘Cameroon is not that big; I can live in Kribi and play music in Douala or in Yaoundé.’“

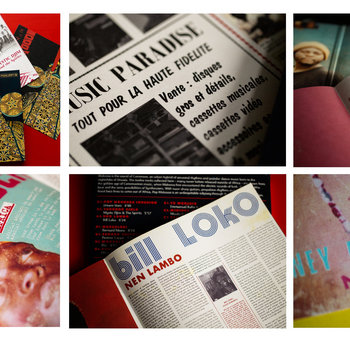

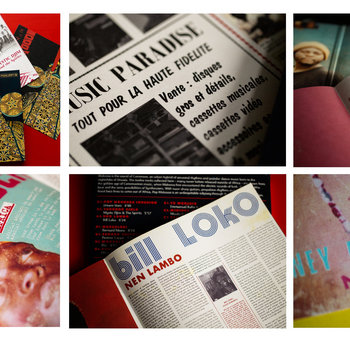

In the mid ’80s, Cameroon was in the midst of an economic crisis. While Makossa had thrived in Cameroon on a grassroots level after the country gained its independence, during the time of economic downturn, few recording studios in the country were able to keep up with the growing demand. With prospects low, many musicians travelled elsewhere, mostly settling exclusively in Paris, where Makossa defined a new underground within the French capital’s endless supply of nightclubs and drinking spots. Record labels, radio stations, and music studios soon followed, and fueled what came to be known as “Makossamania” across Europe and West/Central Africa. The movement was further defined by labels like AfroVision in Paris, and the music was pumped into people’s homes by the famed Africa N°1 radio station.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

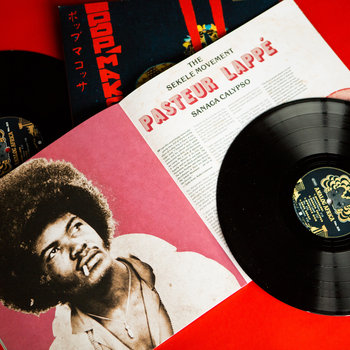

L’Equipe National du Makossa (“The National Makossa Team”) were one of the premier Makossa “hit”-making factories; it was a supergroup formed of Cameroonian musicians including Manu Dibango, Eko Roosevelt, Toto Guillaume, Aladji Touré, and several other high-caliber musicians. The band averaged 50 gold records per year, and scored tracks for many of Makossa’s then-rising stars. One of those names was Bill Loko.

The 1980 release “Nen Lambo” sent Bill Loko into Cameroon’s pop upper echelons almost overnight; it was Makossa’s “Thriller” equivalent, if you will. As “Nen Lambo” played throughout every street corner across Cameroon, Loko, a student at the time, found the attention all too sudden. “He couldn’t walk the street without people recognizing him,” Redjeb says. “There was an explosion after ‘Nen Lambo’ hit the airwaves and everyone wanted to hear that song. People went mad, but he felt like his privacy was jeopardized.”

Perhaps Makossa’s biggest influence on the global dance scene, accidental as it was, came with the emergence disco in the early ‘70s. David Mancuso’s famous NYC epicenter of dance party hedonism, The Loft, helped cement many of the disco traits we associate with the genre today, like bellowing brass sections, euphoric chants, and guitar-driven, four-to-the-floor rhythms. Adopted by the dancefloor and given cult-like status amongst the loyal Loft patrons from its very first spin, Manu Dibango’s “Soul Makossa” became an unlikely hit and one of the first disco records to hit the U.S. Billboard Top 40, peaking at #35 in 1973. Other than its name, the song shared few characteristics with the soundtrack to Cameroon’s streets at the time. Musically, “Soul Makossa” was closer to American jazz and R&B than any form of authentic Makossa flavor. It was a Westernized form of Cameroonian dance music that was easier for younger crowds to comprehend on first listen than many Makossa records of the time.

Through this one-hit wonder (at least on U.S. soil) Makossa had gained international acclaim. Michael Jackson’s “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’,” Kanye West’s “Lost in the World,” and Rihanna’s “Don’t Stop the Music” have all sampled Dibango’s chant of “ma-mako, ma-ma-sa, mako-mako ssa.” Few Makossa records would reach the heights as that of Dibango’s, but in one way or another, Makossa stars continued to be born long after disco had died, and the genre has evolved into fresh ways of dancing for the new generations. Today, Makossa lives on, albeit in more auto-tuned forms through names like Hugo Nyame or Jacky Kingue. With that, Cameroon’s dance beat has never stopped, and Makossa still has its soul.

—Jack Needham