When Brother Ah comes to the door, he extends one hand to shake and carries an autoharp in his other. “C’mon in,” he says, smiling broadly. He is remarkably spry for an octogenarian, eager to explain the ritual he was engaged in. “I was just playing to the plants.”

We’re at his house in Takoma Park, a largely residential neighborhood in the northwest corner of Washington, D.C. There are several potted houseplants in a sunny alcove of his living room; he says he can tell when they respond to the sounds he makes every day. He later tells me he also plays for animals and insects, often during early mornings in the forests of Rock Creek Park a mile to the east. He’s also played for his late dog, or for the robins which took up residence above his front door. Brother Ah plays to connect with, amplify, or complement the naturally-occurring frequencies found in nature, and for his own meditation, circulation and self-healing.

“People feel as though they’re superior, or separate,” he says. “We think we’re the only ones with a higher consciousness. We have to realize that we don’t have the intuitive understanding of many of the other aspects of nature. They’re far ahead of us.”

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

At 82, Brother Ah (whose given name is Robert Northern) has made plenty of music for other humans too: for orchestras in European concert halls and Broadway pits; for recordings with jazz greats like John Coltrane, Sun Ra and Thelonious Monk; for club dates while fronting a worldly jazz combo; for kindergarten students and Ivy League undergraduates; for music therapy sessions in hospices. He still teaches the roots of music to young children at Jamon Montessori Day School in nearby Silver Spring.

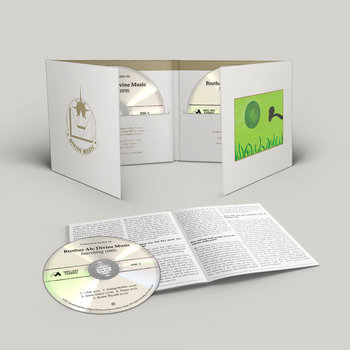

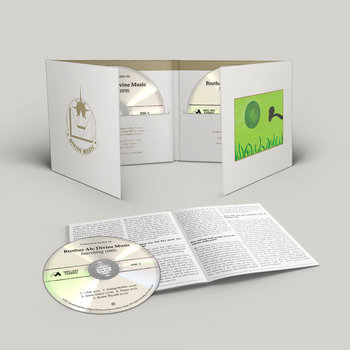

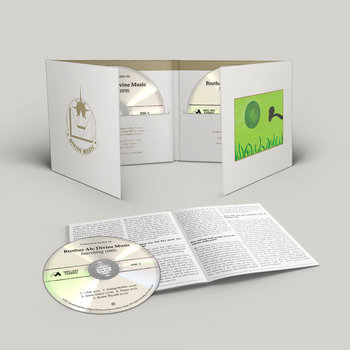

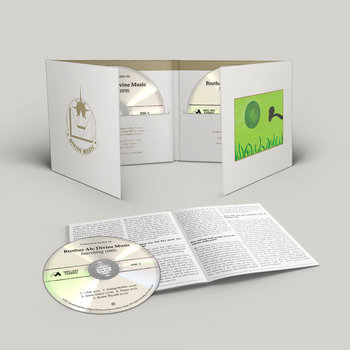

Last year saw the reissue of three of Brother Ah’s studio albums through Manufactured Recordings, the reissue-specific arm of Brooklyn’s Omnian Music Group. The same company has now produced Divine Music, a deluxe box set of Ah’s unreleased recordings, comprising three different album-length projects made between 1978 and 1985, available in LP, CD and digital editions. It is a stylistically diverse collection—you might call a part of it “cosmic” or “spiritual” jazz influenced by African musics, but other sections are genre-resistant improvisation featuring simulated animal noises, synthesizers, flutes, xylophone, hand percussion, muted trumpet, and chants.

These vibrations fit into an overarching philosophy of “sound awareness,” evolved from a lifetime of listening. Nowadays, Brother Ah doesn’t expect anyone to still be aware of his work. He’s always had modest commercial intentions for his recordings and was never “out for name, for fame, or for money,” he says. The contents of what is now Divine Music laid dormant in a file cabinet for decades.

“Everything in God’s time,” he says.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

Robert Northern was born in 1934 in North Carolina, but spent much of his childhood in the South Bronx of New York City. He was drawn to jazz, and even took trumpet lessons from bebop pioneer Benny Harris as a kid. Later, he’d pick up the French horn while attending New York’s High School of Performing Arts. After performing the horn solo in Dvorak’s “New World” Symphony during a school recital, a representative of the Manhattan School of Music offered him a full scholarship on the spot.

At conservatory, Northern met many of the musicians he’d eventually work with—future jazz greats like Donald Byrd, John Lewis, and Max Roach. Unlike his jazz-oriented peers, Northern pursued a European-classical-centered path on the French horn. Following military service, he landed at a conservatory in Vienna and in an orchestra in Germany. When he returned to New York in 1958, Northern obtained gigs with the Metropolitan Opera orchestra and with pit bands for Broadway musicals.

Since he was familiar with jazz, Northern also fielded calls by jazz composers and arrangers when they needed players, which is how he ended up playing with Quincy Jones and on John Coltrane’s 1961 album Africa/Brass.

He often didn’t solo on the French horn, that is until he gigged with Sun Ra, the keyboardist and bandleader who’d moved his large ensemble to New York. Of all his jazz gigs, perhaps his experience in the Sun Ra Arkestra left the greatest impact on Northern, particularly with respect to free improvisation.

“I was concerned about that,” he recalls. “When Sun Ra said he wanted me to take solos, I would always say, ‘Sun Ra, what are the chords? I don’t want to play stuff that’s not in the right chord.’ He told me, ‘Forget all your rules that you learned in school. In my band, the only rules are the rules of nature.’”

Eventually, Northern became a composer and bandleader himself. But to hear him tell it, his first brush with a composer’s pen wasn’t really a conscious act. One night in the late 1960s, he came home from his Broadway gig to “a very spiritual experience” the likes of which he’d never felt before. “I felt very strange—I really did feel strange—and sat on the edge of my bed. I went into a meditative zone, and left my environment,” he says. “And I heard all this music.”

When he woke up at dawn, Northern says he wrote down as much of his vision as he could remember. He arranged it for a small ensemble and scrambled to record it himself. The resulting work, the narrative sound college “Beyond Yourself,” was eventually released a few years later on the album Sound Awareness, one of the three albums reissued last year.

Another eclectic improviser—trumpeter Don Cherry—put Northern in touch with his next big gig: substitute teaching a course at Dartmouth College. One semester became three years—it was actually his students who gave him the nickname Brother Ah, perhaps as a play on a vocal tic of his—and the Dartmouth position led to a different position at Brown University.

Life as a professor had its perks. He took summers to travel, often to Africa, to study different musical cultures. He recruited students into his ensemble, the Sounds of Awareness. He had time to consider the music he wanted to make for himself, and it didn’t necessarily involve the French horn.

The first part of Divine Music, the 1978 project called The Sea, is easily the most conventional in form and concept. It’s derived from his work with the Sounds of Awareness band, with a bass and drum kit anchoring a grooving rhythm section. It also features the obbligato bowed strings of Lauren Tjane Elliot and the strong, clear singing voice of Natasha Hassan Yousef. Brother Ah is heard throughout on flute.

He says the genesis for this set of works came from a night on the beach in Jamaica. “I spent the whole night sitting there listening to the music—I call it music—the sound of the waves, and all of the different sounds,” Brother Ah says. “And from that came this beautiful composition.”

His study of music in Africa—East and West, urban and rural—also figures heavily into The Sea. Hand percussion and harmonic modes filter into the undercurrents and song structures. And there’s a strong appeal for an ideal of pan-African pride, especially in songs like “The Village Drum” or “Africa We Are Your Children.” The latter, he says, was a plea for acceptance, borne of the chilly reception he occasionally perceived as an African-American among native Africans. “For me, to be an African, one doesn’t have to be born in Africa—Africa was born in me, in us,” Brother Ah says.

A few years later, 1981’s Meditation reflects Brother Ah’s African travels in a vastly different manner. Whether deep in East African or Ghanaian bush—or on a farm in rural Vermont he owned for several years—Ah does much of his meditation outdoors. So when he tasked himself with creating music for meditating, he laced it heavily with emulations of the sounds of animals and other natural phenomena.

The final album in the Divine Music trilogy, 1985’s Searching, is also a duo session made for personal purposes—“healing and spiritual consciousness,” Brother Ah says.

It stemmed from many jams with Richard Ashman, an engineer at a studio across town. Ashman plays the synthesizer beds and some percussion, and Brother Ah—adding to his flutes, harmonica, hand drums, and conch shell—also picks up the trumpet, his childhood instrument. He describes the session as “spontaneous creativity,” without preconceived forms. The density of Ashman’s synths suggests a sound collage, but Ah says there are no overdubs or post-production edits.

Song titles like “Prayer” and the presence of chants also suggest a divine inspiration. The album title comes from an experience he had as a teenager. “One day the priest from the Catholic church … came to my house and told my father that I hadn’t been to church, and had so many sins now,” Brother Ah recalls. “My father said, ‘My son is searching.’”

Brother Ah’s career as a public performer and recording artist has slowed in recent years, but he’s far from inactive. He still makes music for others, especially with an all-female string ensemble, though these days he’s limited to music therapy sessions and other private rituals. For nearly 20 years, he’s hosted a weekly on-air jazz program for radio station, WPFW. All the while, he has actively taught music at all levels in the D.C. area.

“It’s amazing what they hear,” he says of his Montessori school students. “I walk them down U Street, where all the traffic is, and you’d think they wouldn’t hear anything except the buses and the horns. All the birds that they heard, all the insects—all these things they heard, these children are hearing it. They’re more connected with it. With an adult, they don’t hear anything.”

On my way out, Brother Ah walks me into his basement studio. There are instruments of all sorts to complement the zither and piano and xylophone upstairs: Western flutes, bamboo flutes, wooden flutes, homemade flutes, a didgeridoo, hand drums, and a conch shell. Photos of departed peers like Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach (“ancestors,” in his parlance) are a reminder that he is among the last of his generation, and it’s clear that that although the term jazz can describe only a portion of his career then and now, he feels an obligation to celebrate the history at the root of his endeavors.

I finally get a look at the Divine Music box set sitting on his dining room table—the packaging, the extensive liner notes, the original painting of him that became the booklet artwork. Even after our detailed discussion, he still looks for morals to the story of why, after all these years, his forgotten creations are just now coming to light.

“I really, really, really want to encourage people to stick with your goal,” Brother Ah says. “I didn’t compromise, I didn’t go commercial, I didn’t add a lot of junk stuff. I just left it pure as it came to me. And now people are ready for it, I guess.”

—Patrick Jarenwattananon