One sleepless night in 2009, I experienced a revelation while alone on the couch. I was a sophomore in high school, I had school the next day, and I’d given over to my habit of letting the gentle murmur of late-night reruns lull me to sleep. In-between the dulcet tones of audience laughter, intermingled with snide comments by a disgruntled Ray Romano or Ed O’Neil (honestly, it doesn’t matter which), I received a commercial for Dell Technologies’s new Studio 15 laptop and, with it, an aesthetic epiphany.

I’ll admit it’s not the most stylish context for such a realization, but when some savvy music supervisor used the bubbly and strange 1999 recording of “I Love You Ono” by French-German lo-fi pop duo Stereo Total to help sell consumer technology, they undoubtedly altered the course of my young life. After some rapid Googling of what few lyrics I could make out (“I love you, oh no…diamond ring…planet Earth?”) followed by a download of the band’s fourth full-length, My Melody, I found myself at the start of a steady unraveling that would last for at least the decade to follow.

“I Love You Ono” was originally written and recorded as “I Love You Oh No!” by Japanese new wave band Plastics on their 1980 debut Welcome Plastics. Lyrically, the song presents an array of luxuries—a diamond ring, a holiday sun, a swimming pool, 16 karat gold, and a silver fox—in a Warholian, list-like fashion with onomatopoeia and exclamations interspersed throughout (“oh no,” “cha cha,” “zap zap,” “bang bang”). The song’s chorus pushes this dewy-eyed fantasy towards a capitalist critique with its absurdity: “Planet Earth presents you/ Big money/ Big system/ Big fame/ Big brother.”

A 1981 review of Welcome Plastics in the American magazine Trouser Press called the album “extreme kitsch and quirk,” and remarked upon how the group’s fascination with technology aligned with their “clever, nervous, and zany” sound that was reminiscent of “the B-52’s and Devo.” This fails to mention, however, the stark minimalism of early Plastics, which is presented with spacious and thin oom-pah drum machines, dry guitar, cleanly synthesized sound effects, and voices that often land more as squeaks than melody.

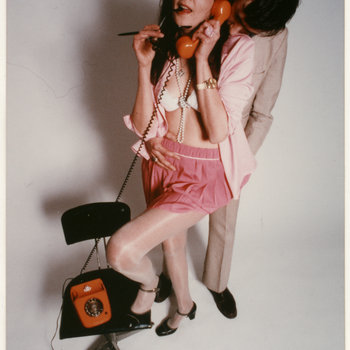

Stereo Total’s 1999 cover of “I Love You Ono” is largely faithful to the original, down to the smallest synth sweep and vocal squeak. In the 19 years between the two records, the biggest change is that, while Plastics opt for a slick undistorted surface, Stereo Total’s is clipping in every way it can. Vocalist Françoise Cactus howls through the lyrics with a distinctive rasp, embodying the specific chaos of the maybe-a-little-too-drunk-and-delusional dilettante at the song’s center. Her voice slides between melodic leaps, somehow hitting the right notes on the other side while a high-camp cacophony of synth, guitar, and drums blares behind her with a certain lopsided but mechanical steadiness. Despite all its subversions, the song is pure pop, and because of that, it was unlike anything I admitted to enjoying at the time.

Growing up as a young punk in Southern California, most of my friends were boys who skated and/or played guitar. Through our pre-teen years, our collective listening followed a trajectory that went broadly from classic rock to ’90s skate punk and emo before boomeranging back to the early manifestations of punk and metal. Music with female vocalists was rare but not entirely forbidden. The usual suspects like Heart and Bikini Kill were eventually welcome, smuggled into our taste under the auspices of a notion that they could play like the guys.

When I was about 14, I gravitated towards more subversive bands like Devo, Suicide, The Stooges, Crass, Bad Brains, and Dead Kennedys. I hand-stenciled a light-gray hoodie with a teal X-Ray Spex logo and proceeded to wear it almost daily regardless of the weather. I remember marveling at the way Poly Styrene’s voice leaped around her band’s firecracker rhythms and DayGlo melodies, propelling the music towards something between fury and elation.

At that age, I didn’t think twice about my identification with X-Ray Spex. I rightfully understood that their music could and should be enjoyed by all types of people including teen boys. In retrospect, however, I have to acknowledge the degree to which I identified with their music and consider why that might have been. Both X-Ray Spex and The Buzzcocks (another early favorite, led by the openly bisexual Pete Shelley) used snappy pop structures to critically explore topics of gender, romance, and sexuality with nuance and fascination. These explorations were well enough couched in the once-revolutionary fervor of punk that my appreciation of their more amorous, traditionally feminine themes was concealed.

In a 2001 thesis paper, The representation of the feminine, feminist and musical subject in popular music culture, author Emma Mahew cites a 1995 study by German theorist of U.S. culture Ute Bechdolf that demonstrated how “male audiences in research tried to distance themselves from music videos they saw as girl-orientated,” which often correlated with “soft rock” and “pop.” Mayhew states that this shows how male listening is often governed by “a dichotomous understanding of gender and musical taste.”

Mahew likewise points to a 1997 essay by Norma Coates, who studied the developing relationship women had with rock music through the ‘90s. Through this research, Coates found “that there is still a hegemonic hierarchical divide between rock and pop as two distinct genres which reflect gender difference,” the former historically being a genre worthy of critical value while the latter could be considered commercial fluff. For me, Stereo Total bridged this divide, bringing the explicit joys of pop into an aesthetic that resembled rock, loosening my misconceptions about candy-colored music and opening my understanding of what was available to me.

Stereo Total was the first in a continuum of personal musical discoveries that continued through the third-wave feminist electroclash stylings of Chicks On Speed on to the cyborg sonic revolution posed by SOPHIE to the endlessly self-aware twee of Kero Kero Bonito to the sensuality and ecstasy of Janet Jackson and finally the simpler pleasures of Carly Rae Jepsen and Ariana Grande’s sucrose melodies. Accompanying this chain of appreciation was the gradual reassessment of my own once-buried femininity and complicated relationship with masculinity. In parallel to my burgeoning love for this music and my steady identification with it, I had another realization that perhaps I was not a man.

Nine years after I first heard Stereo Total, I began to understand myself as a trans woman. Unlike the commonly propagated narrative of a trans person who had known their proper gender since birth but had simply been trapped in the wrong body, my trans awakening was very much a surprise to me at age 26. If it wasn’t for my already developed taste for art and writing by women and about women, it would have been even more surprising and I think I would have found myself much more lost. When it came to transition, I tended to let the music guide me.

Of course, I should note, liking artists such as those listed above doesn’t innately make one a woman, and not liking them doesn’t make one a man. I’m less interested in how identity might determine taste—or vice versa—than I am in how they might mutually inform one another constantly. Music has always had a stronghold on both the formation and expression of my sense of self. Take, for instance, the way bands like The Clash and Crass helped shape my political sensibility early on while simultaneously providing an avenue for expressing those sensibilities. Likewise, the role of music in helping me understand my gender has been ineluctable. In many ways, my shifting relationship to gender over the past thirteen years can be most easily understood through my gradual understanding that my love for Stereo Total and others like them was not an appreciation of, but an identification with them.

Because my friends and I were white, suburban, and middle class, it would be years before we overcame our learned prejudice towards drum machines and sampling. Because we were boys it would be years until we overcame the subtler learned prejudice that taught us to favor guitars over synths. In her book about Wendy Carlos’s 1968 landmark album, Switched-On Bach, Roshanak Kheshti notes the piano’s historic role in the domestic “performance of Victorian womanhood” before exploring what that history means for our perception of the synthesizer—the piano’s unnatural, malleable, cheap imitation. Paraphrasing an early, negative review of the landmark album, Kheshti writes, “The synthesizer is the dildo to the real man’s piano/penis.”

Considering this, Kheshti reflects on what was, to her, a formative viewing of a performance by Stereolab, describing a sort of feedback loop of meaning-making: “[The] sound of fantasy arose at the juncture between the instrument and its performers, women who seemed to intersect with the instrument, causing a resignification of not only the Moog but also of womanness; the women players altered the Moog, but the synthesizer also altered them.”

In a self-published 2020 essay titled A Sex Close to Noise, Leah Tigers writes of an affinity many transfeminine people seem to have towards blurring distinctions between noise and music. Tigers broadly posits that this affinity might stem from an impulse to harness and redirect the alienating gaze of cis society and shape it into something we can call our own.

As an example of this oft-commodified cis gaze, Tigers points to the way Lou Reed used trans women as a conduit for wildness on his most famous song “Walk On The Wild Side.” As an example of the reappropriation of this wildness, Tigers points to Jackie Curtis’s virtuosic performance in the broadly sexist and transmisogynistic, Andy Warhol-produced and Paul Morrissey-directed Women In Revolt (1971), where one can find the actress improvising a caricatured but still-scathing form of transfeminism. Tigers describes this work as “the labor of articulating your own condition,” a way of arresting narrative and meaning-making devices like music and art from a patriarchal society that would rather do it for us.

This leads me to consider the noise made by Stereo Total members Françoise Cactus and Brezel Göring, where it might have stemmed from for them, and what I once found liberatory about it. My Melody’s opener “Beauty Case” is Fashion Week rendered uncanny by chaotic layering, a wobbly pulse, and sudden shifts between sections. The beat for “Du Und Dein Automobil” somehow incorporates more than one regularly recurring sample of a car skidding out. On “Discjockey,” a noisy, makeshift attempt at an acid house beat bolsters Cactus’s declaration “je suis okay, je suis discjockey,” a functional mantra for more than a few trans girls I know. Even a melancholy ballad like “Larmes Toxiques” explodes at moments with rapidly arpeggiated synths, more reminiscent of “game over” screens than as actual accompaniment.

Throughout it all, Stereo Total’s noise on My Melody does not sound to me like the noise of careful mastery, such as that of Jackie Curtis, Wendy Carlos, Jordana LeSesne, or SOPHIE. Instead, it’s an incidental noise, one that arises from a comfort with (and perhaps a comfort in) mistakes. It’s the sound of distortion, of playing in the red. It’s watching a machine at work, noisier and more cacophonous than simply seeing a final product. It’s a messy masterpiece of the highest order.

In this light I consider another aspect of Stereo Total’s work, another source of my admiration for them: their unabashed fandom. They were broad and deep listeners, producing sunshine pop by way of Shibuya-kei, ’60s R&B by way of yé-yé, and lo-fi by way of komische. They made it clear at every turn that their cultural interests were vast and fanatical, with candid references and tributes to Serge Gainsbourg, The Beatles, Andy Warhol, Yoko Ono, KC and the Sunshine Band, Velvet Underground, Salt-N-Pepa, David Bowie, Brigitte Fontaine, filmmaker Pedro Almodovar, and cult actor Divine. My Melody alone contains six cover songs, paying tribute to artists as disparate as Cher, Japanese art pop group Pizzicato Five, German performance art group Die Tödliche Doris, and French model/pop star Vanessa Paradis. This fandom is a crucial aspect of Cactus’s lived and embodied commentary on womanhood.

At the birth of pop music in the ‘50s and ‘60s, young women were considered a crucial market, namely because they were seen as passive and easily manipulated. Mayhew considers research on fandom that shows otherwise, stating that “the activities of female audiences of the 1950s and 1960s have been reexamined by feminists as an empowering and active experience for women rather than as an empty and passive one.”

Mayhew looks to research by John Fiske that points to productive fan practices, including the simple act of “making meaning out of commercially produced texts” as well as the production and circulation of new “texts” (i.e. fan clubs, fanzines, fanfic, and fanart; or consider a hand-stenciled X-Ray Spex hoodie that one might wear every day regardless of the weather). Stereo Total’s predilection towards the cover song, tribute, allusion, and pastiche is not simply derivative, but a reclamatory act of meaning-making, a way of owning for themselves the pop culture they’d been fed. It’s their own highly productive form of fandom.

When Cactus slurs her way through the hook of Salt-N-Pepa’s 1987 hit “Push It” over a garage rock riff culled from a synth line, she is not only celebrating the sexual wonder and joy of the original but enacting a form of feminine production that rejects passivity by redirecting the energy of art and media consumption into something new. The duo’s cover of “Ringo, I Love You”—a song about Beatlemania written by murderous creep Phil Spector to be performed by Cher—explodes the cool, daisy-in-her-hair demeanor of the original, more accurately presenting some of the feverish vibrance of Beatlemania itself, with Cactus’s voice clipping to near-unintelligibility throughout.

Now, I sit here with a tightly cropped head of hair and a voice that sits well below what is typically understood to be a feminine register, writing 2,500+ words on an album I heard a decade ago, performing the role of the fangirl in my own demented way. Occasionally, when I write—continually dancing around and picking apart a topic—my subject deadens before me and I have to keep prodding it to coax out the meaning. In this case, however, it only continues to grow more vibrant. I recognize new dimensions and depths to what originally spoke to me about Stereo Total. I recognize what parts of My Melody are with me today, aspects of myself that it either actively formed or that it gradually drew out of me.

Regardless of which one it was, Françoise Cactus showed me a path to womanhood which was both grounded in traditional notions of femininity and which resisted those same notions at every turn. Her punky, endlessly distorted voice rejected prescribed tropes and roles while delivering chipper bubblegum melodies about boys she loved. On “Ringo, I Love You” she was the fangirl par excellence, whose scream marked the timeless angst of adolescent girlhood, a dominating sound pulled out from the very lexicon of submission. In this way, “I Love You Ono”—Stereo Total’s tribute to Yoko Ono by way of The Plastics—is all too fitting: a scream piece which bursts through all forms of co-optation, speaking past the rows of laptops, camcorders, and perfumes on display, past prescribed gender roles and fixed notions of self, to an adolescent girl who didn’t yet know she was.

Leah B. Levinson’s writing has appeared in Bandcamp Daily, Tone Glow, Post-Trash, and Tiny Mix Tapes as well as her own newsletter Happiness Journal. Leah also makes music as Cali Bellow and performs in the ecstatic black metal band Agriculture. You can learn more about Leah on her website and follow her on Instagram at @leah.happiness