Even the most incorrigible maverick has to be born somewhere. He may leave the group that produced him—he may be forced to—but nothing will efface his origins, the marks of which he carries with him everywhere.

–James Baldwin

现实就像 一把枷锁

把我捆住 无法挣脱

Reality is like a yoke

It ties me up and I can’t break free–Wang Feng

There’s an interesting anecdote that a friend once told me. It goes something like this: a Chinese American studying abroad in China grows tired of locals’ unbelieving reactions to her admission that she’s capital-A American. To them, an American with a Chinese face is an ontological impossibility. She begins to introduce herself as Chinese American, but this requires the trouble of having to recite her parents’ immigration history to everyone she meets. Exasperated, she finally claims to be Korean, which works brilliantly. No one is curious about a Korean living in China, the country’s most populous foreign group.

The story is taken from the introduction of Chasing the American Dream in China, a sociological study of Chinese Americans returning to China. I find her anecdote amusing because I am living its (partial) inverse. I moved to Korea last year, and nearly everyone initially clocks me—a Chinese American—as Korean. I derive a strange pleasure from maintaining the illusion: if I don’t open my mouth, I move about freely, almost invisibly, just another Korean-ish face in the crowd.

—

June 2019: I am at a Taipei dive bar, moshing in a sea of black hair. The fact that almost everyone looks like me in an underground music space feels good. Yet the odd foreign face irks me, reminding me of my own “unpleasant Americanness,” the same affliction that plagued David Foster Wallace during his Caribbean getaway.

I visit a film processing studio to develop some film from the gig. Noticing my shaky Mandarin, the avuncular shopkeep asks if I am from Hong Kong. A breath of relief—at least he didn’t think I was American.

—

I left America for reasons analogous to but less urgent than those that drove James Baldwin to Paris. I couldn’t care less about not being “American” enough for America; I wanted to escape being American. It didn’t matter to me where I went, really. I just needed to be free from the land of the free. Looking back, it’s an ironically American mindset to have: that you might absolve yourself of the sins of the settler colony by going abroad, made even more so by the fact that I was receiving lavish foundation funding to do it. In any case, East Asia was where I could most easily blend in with “the locals.” I’d picked Taiwan at first because my facility with Mandarin and familiarity from previous visits would have eased my disguise. But COVID-19 prevented me from applying for a visa, and South Korea was the only other country in Asia that was open for immigration, so I let myself be swept into the Hallyu.

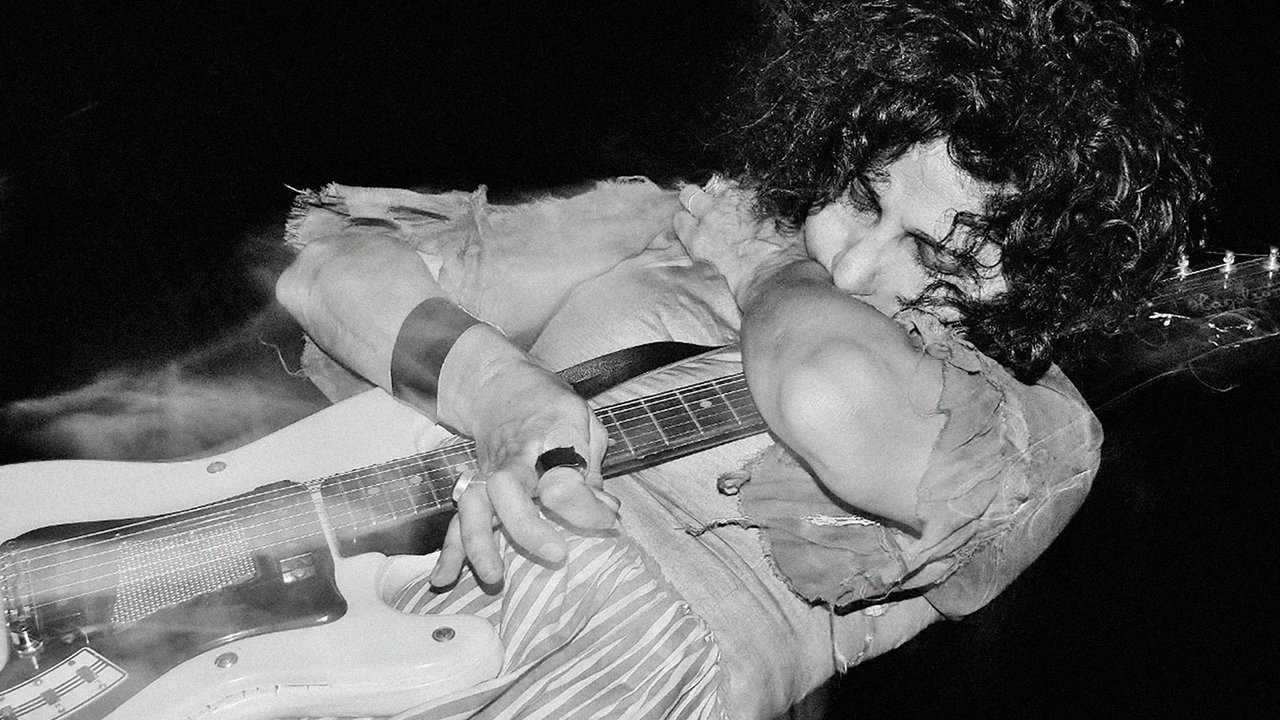

It was in the notoriously chilly Korean winter that I revisited Tim Zha’s music. His solo work as Organ Tapes is a perfect companion to the gray loneliness of hibernal flânerie, a cold sound with traces of warmth. He cooks up this effect with synthesizers, MIDI instruments, drum machines, guitar, and a cocktail of AutoTune, reverb, and warbling vocal delivery. In a certain ratio, it emerges as the cybernetic dream pop of his latest album 唱着那无人问津的歌谣(Chang Zhe Na Wu Ren Wen Jin De Ge Yao); ease up on guitar and sprinkle more club (from dancehall to deconstructed) to get Into One Name; go between the two for Hunger In Me Living.

Unifying all this is a crying-in-the-club sensibility that appears throughout his oeuvre. It’s the kind of music I love now because I loved Elliot Smith, Nick Drake, and Sufjan Stevens in high school; back then, I hadn’t yet discovered Asian artists who channeled the melancholy I craved. But it’s Into One Name that I gravitated to while walking at night in Seoul, letting the bass of “Di Qiu” wrench the piercing cold from my body. This record, taking influence from the club but designed for headphone listening, represented for me the limbo of Seoul’s music scene as COVID-19 curfews continued.

All of this is to say that Zha’s music is that of the in-between, sonically and thematically. Seeing music critics struggle to pin down his sound is always entertaining (and I hope to continue to entertain.) His Autotuned vocal shambling connects the dots between Sarah Records and mumble-rap, rendering his lyrics half-intelligible, often ambiguous. And, of course, his biography is relevant here: he’s half British, half Chinese, growing up between London and Shanghai. But he doesn’t make music about diaspora; his lyrics, when you can make them out, are more often impressionist musings on love and spirituality (“Love you like I never did/ You were my angel like I thought it could be heaven-sent”) rather than the between-two-worlds narrativity of Seam or Mitski. He rarely tells; he shows—and if he does tell, the words are obscured via human and computer-generated means. It’s through his approach to presenting himself in his music that I’ve come to understand why I feel comfortable in Korea.

—

March 2022: I am in a club in Itaewon, DJing to maybe 20 or 25 people dancing feverishly, as if to pack as much fun into the two hours before 9pm curfew. Having appropriated the nostalgia of my gyopo friends by soliciting their favorite noraebang selections, I think I have the perfect closing track. I mix in a single from a late ’90s one-hit-wonder, the breakbeats of Oraksil’s “Hu” driving toward its absurdly catchy chorus. A local DJ friend screams with recognition and joy: “How the fuck do you know this song?”

—

I should be clear: I arrived with as much knowledge and interest in Korea as is appropriate for a Chinese kid who grew up in rural Connecticut but came of age in Orange County: Somewhere between Koreaboo and just normal American. To escape the latter, I immersed myself in “Koreanness”: learning Korean, hiking with ahjussis and ahjummas, accepting their overeager offers of mid-hike soju swigs. For my efforts, I’ve become gyopo-passing, enjoying the benefits of “being Korean enough” without the fears and insecurities that not being Korean enough might entail. Because I’m not actually Korean, that chiastic complaint beaten to death by the diaspora doesn’t apply.

I used to think that the ease with which I could simulate “Koreanness” had to do with Korea’s history: the erasure of culture during Japanese colonialism, the violence and fragmentation that defined life during the Korean War, the continued occupation of the South by the U.S. In this country that has lost so much, the urge to construct and present an essential “Koreanness” sometimes feels like an existential necessity. Korean rhythms come in threes, home is where the Han is, and so forth. When cultural essence is thus contrived, it’s easy to reverse-engineer belonging.

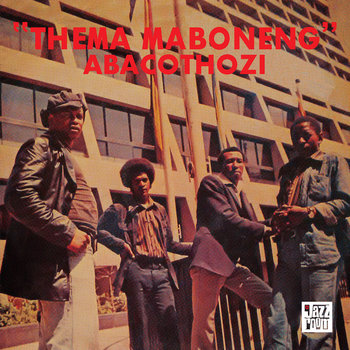

But I learned to be Chinese American in the same way; just swap out the references. I feel a kinship with Zha because I grew up listening to my father belt Wang Feng lyrics during road trips; much later, I would access this nostalgia intentionally, asking them about the songs of their youth. So when Zha puts his own spin on Wang Feng in “Li Bu Kai,” I get it. He understands, too, that Wang Feng isn’t the sexiest or most hip reference: the U2 of China. Yet he appropriates his work with sincerity and confidence. Everything about Zha’s music is singular, standing for itself, nothing more or less. The dialogue sampled at the end of the track is a man asking a woman something along the lines of, “Why didn’t you leave if you had the chance? Why?” The tautological answer might be in the song’s title, translated to “inseparable” or “unable to leave.”

None of this is exotic or unknowable to outsiders. Anyone can get it if they learn the references or language, so what makes it different for me? What else does belonging boil down to than a relationship to cultural, historical, and political signifiers? The nostalgia that an English teacher has developed for “Hu” because it reminds him of when he first moved to Korea feels like it should somehow be different from a Korean’s, or even mine. Of course, race matters. It’s why, in one, less exoticizing account, Japanese Breakfast has that eyebrow-raising moniker: because East Asians, when it comes down to it, look alike.

I suppose this is also why Zha quotes Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben in the digital liner notes of Into One Name. The source of much diasporic angst is the disconnect between one’s perception of themselves and how others perceive them. Cue the chiasmus. The diasporic subject wants to be loved not for their Asian-ness or American-ness but “with all [their] predicates,” as an unhyphenated being. The logic of inclusion necessitates exclusion; Zha’s fugitive sounds have shown me why I’ve been able to free myself from that strict dualism in Korea.

Zha revels in these sorts of contradictions. “I think…paradox is always central in a lot of what I make,” he once said in an interview. “The irredeemable redeemed by Grace, the tainted made pure by Faith, the coincidence of the Worldly and the Heavenly, etc.” And just as Zha channels this “zone of indistinction” in his music, I realize I’ve been exercising the freedom that comes from straddling the line of inclusion and exclusion, the freedom of the in-between. It’s the “intelligence of an intelligibility,” an acknowledgment that I am racialized in such and such way and can therefore act accordingly, that there’s power in ambiguity. I will never be Chinese Chinese, Korean Korean, or American American, and that’s an incredibly freeing notion. This lack of belonging doesn’t have to be a source of angst. Instead, it allows me to indulge in learned nostalgia, play with belonging and community.

You can hear that sense of play in Zha’s club blends (as DJ Corpmane) as well. Drawing connections between alt-rock and baile funk, Soundcloud rap, and hard drum, his edits remap a wide range of sonic territory. YB and Dis Fig do this too, and I’d like to suggest that their musical syncretism and diasporic experience are connected. At the very least, it is for me.

Baldwin eventually found his origins in America inescapable but ultimately realized those very origins were where his power as a writer lay. For me, it’s my position within this space between intelligibility and obscurity, between essence and potential, between Incubus and Mc Léo da Baixada that I find “a matter for rejoicing.” I, the perpetual foreigner not belonging to this or that group, instead become “whatever” (as Agamben would have it), transcending the binary logic of neoliberal identity politics, allowing myself to be as I am not.