Where Judith Butler has long been recognized as the main theorist of gender performativity—the idea that stylized, repeated gestures (re)inscribe some supposedly cogent identity—Butler spends much of her time now asking whose lives are “grievable” and, particularly for oppressed peoples, how grief evolves. Whose deaths are permissible; whose aren’t? What does it mean to perform grief; how does it look or sound? In a 2002 lecture, Butler points out how, like gender, mourning is a process where we negotiate fluctuating roles with one another. As we live our daily lives, we settle into webs that become essential to our self-conception: parent, friend, sibling, comrade, etc. When an interruption like death alters that relationship, we’re forced to renegotiate.

I’ve realized that I’m often in mourning. I’m used to calling the high velocity outpouring that manifests post-tragedy “mourning,” but most grief is gradual. Amid the changes I saw between adolescence and adulthood, I couldn’t predict how my relationships would transform. I mourn people whose presences I miss, the geographies I left behind, and the manifold versions of myself that I shed like dead exoskeletons. I feel like the same person I was a year ago, or even as a teenager, but more refined. But just as my circumstances have varied, I have shed pieces of my previous lives and adapted, morphing into someone who I can only vaguely recognize.

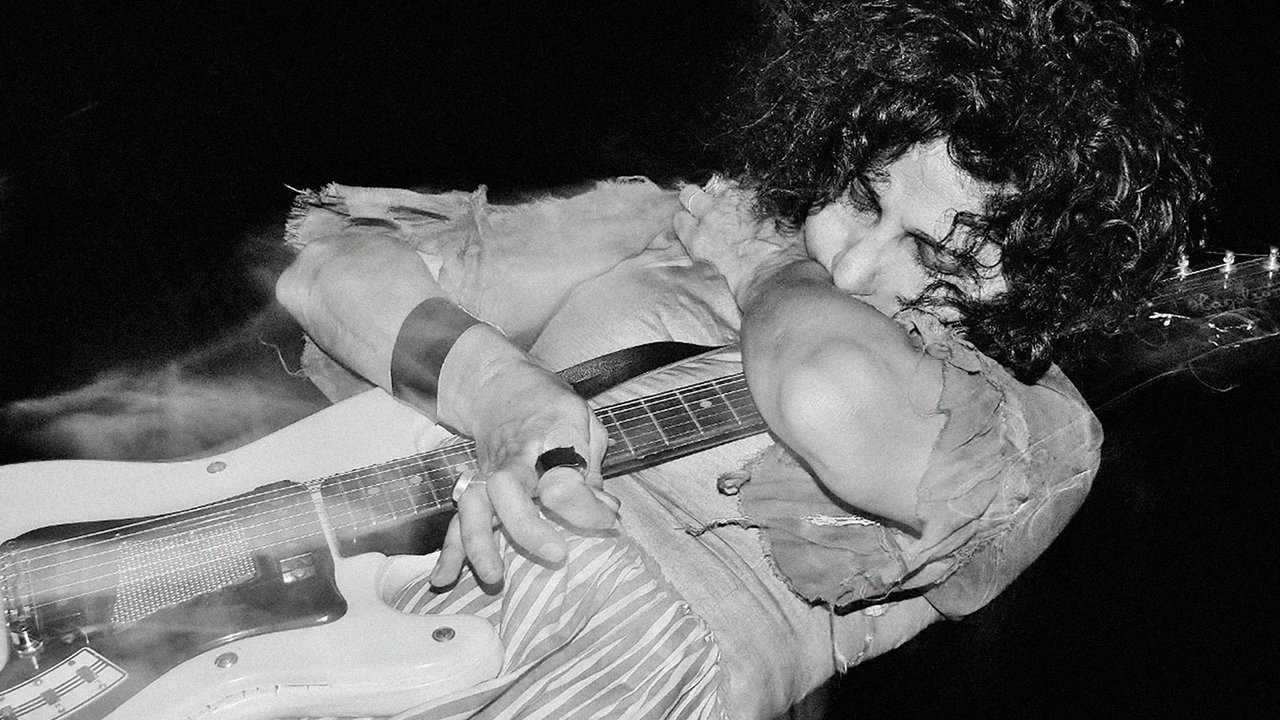

When Haley Fohr, best known for her experimental project Circuit des Yeux, approached her 2021 record -io, grief was on the brain. A beloved grandmother passed in isolation; a close friend died “methodically;” a looming cloud of despondence during a residency on Captiva kept her from pivoting the Circuit des Yeux project towards joy, as she’d intended. The pandemic derailed her then-upcoming Jackie Lynn tour and exacerbated her economic and artistic precarity. Reckoning with her new roles in the constellation of her family, her friends, and her artistic community begat the grief with which she fought as she arranged –io for her four-octave voice and a precision-balanced orchestra.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

My partner sent me -io on a late afternoon when work was getting to me; I was alone in my office, too overwhelmed even to flip the lights on despite the sun slipping behind the late autumn horizon. -io is striking; I uttered “holy shit” at the climax of each track. But it was “Stranger” that stopped me at my desk, where I doubled over in unrepentant sobs.

By -io’s standards, “Stranger” is bare: voice, piano, string bass. It’s a fatal combination. As Fohr bears witness to the figure of the stranger, contemplating her past and their interconnectedness, the voices remain close and then abruptly diverge. Fohr hurls her voice to the top of her four-octave range as the bass rings its lowest open string. I freeze every time I hear it. When you mourn the way Fohr is mourning, strangers become potential counterparts. Just as your relationship to the deceased has changed forever, your relationships with yourself and others are transforming. It’s a mystery where you end and where strangers begin. Are strangers not just potential counterparts? Are their livelihoods more familiar than not? How are we connected? When your closest relationships are in flux, strangers seem closer than ever. Strangers possess the capacity to become anybody to you.

When I hear “Stranger” now, Fohr’s puissance still overwhelms me, but what strikes me the most is the double bass. As Andrew Scott Young enters tremolo sul ponticello, I’m reminded of the bassist I used to be and the bassist I never became. Growing up outside of Cleveland in the mid-2000s felt like watching your career choices evaporate before you knew what a career was: deindustrialization punched workers while they were down, foreclosure hung over everyone’s head, and the “good jobs” weren’t hiring anymore. To an extent, they still aren’t. My school marketed the arts as a reliable tool for social mobility; one where the rules still made sense, where hard work would be rewarded. The first goal I remember setting for myself at 11 was to make it into the high school rock orchestra on my instrument of choice: the double bass. I practiced my Simandl etudes and my Vance arrangements until my callouses bled. For as much sweat as I poured into that instrument, I hesitated to make music performance an official career goal. That felt like something for someone who’d started before me, who came from a musical family, who came from unassailable economic security.

My hunch was partially correct. The arts were advertised as a meritocracy. At first glance, the arts were meritocratic, but merit works in tandem with privilege. Students who had their nascent performance skills bolstered by class privilege still absolutely worked their asses off to play like they did. Only some of them were rewarded with a stable performance career, university scholarships, or other spoils. This hyper-competitiveness can make the classical performance space risk-averse, especially when working with youth. The stepping stones in classical pedagogy, instrument by instrument, feel like commandments delivered by God to humanity. After experiencing conflict in this strict space, I put my bass down. I didn’t fight for it. I regret it often.

When I heard “Stranger,” and ventured back in -io to focus on the strings in “Vanishing,” “Walking Toward Winter,” and “Oracle Song,” I let myself admit that I missed the bass. I missed the orchestral environment. I missed performing formative works in the classical canon, the camaraderie in the bass section, the high of practicing a solo piece until it sounds somewhat correct. In my later high school years, I became acquainted with the works of Koussevitzky, Adams, and Glass. What one could do with an orchestral instrument felt broader than ever before. But as soon as a fulfilling, exploratory path in bass performance appeared before me, it became far more important that my musical pursuits remain strictly a tool for social mobility: university admissions, scholarships, all leading towards a conventional career with the performing arts a relic of my personal history. My mother and I white-knuckled a blizzard to get to an audition on traditional bass exercises for such scholarships. We’d invested more of our money into this six-foot wood sculpture than we thought we would. It was time to make it work for us.

Vinyl LP, Compact Disc (CD)

It is uncanny that something as fundamental as music can be operationalized for the peculiar American class consolidation process of university admissions. During my years of studying the bass, I was running a rat race: adhering to classical pedagogy, auditioning for youth orchestras, performing the standards at recitals. The validation I received along the way made me brim with pride pushing on arrogance; I felt capable. But once I secured admission to college and graduated from the youth orchestra circuit, my rental bass went back to its dealer and I got a liberal arts degree. Now, I’m back in graduate school trying to build a stable livelihood. I thought I didn’t miss the bass; I clearly do.

But even when I revisit a track like “Vanishing,” I feel implicated. As the cello line settles into a groovy syncopation, I can visualize the sheet music passing before my eyes like a conveyor belt of melody. I can place the down- and up-bows. The more I focus on the strings, I sort through the alphabet of performance and dynamic directions happening. Each subtle change on “Vanishing” prompts wonder within me. It takes a minute for me to sojourn back to Fohr’s lyrics, which treat her existential dread with urgency to match the bellowing strings. While I’ve gravitated towards records dabbling in subtlety and obscurity in recent years, bearing witness to this nakedly dramatic music challenges me more than decoding any shoegaze track ever could.

When I hear the legato passages on “Walking Toward Winter,” bolstered by lyrics confessing “I’m changing while I try to hold the reins,” it smacks. Whether it’s a relationship to family, community, art, or self, fluctuations are a given and it’s hard not to feel sorrow when you move on from something you loved. It feels silly to mourn something to which I technically have access—if I move money around, I could rent a bass again—but I dwell on how I was taught to use the bass for forms of economic and social gain I never quite understood. How we operationalize art for class mobility still colors my relationship with music. Maybe with Fohr’s words, I can untangle that.

Devon Chodzin is a city planner and writer currently residing in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. When he’s not studying green stormwater management practices, he can be found at a basement show or writing music features for Paste, FLOOD, Slumber Mag, and more. He lives online: @bigugly