“Air New Zealand safety video divides a nation” read a headline on one of the country’s popular news websites, Stuff. In November, the airline released a safety video featuring local rappers covering Run DMC’s “It’s Tricky”—with the chorus hook changed to “It’s Kiwi.” The video reignited a years-old debate about the authenticity of Pasifika hip-hop, questioning whether New Zealanders are simply appropriating the music of another culture, or are bringing something uniquely “Kiwi” to the genre.

Pasifika hip-hop—or “Urban Pasifika” as it is often known—is hardly new. The first Polynesian hip-hop groups formed shortly after The Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” became an unlikely hit in the South Pacific in 1980. Yet early groups like Upper Hutt Posse, Sisters Underground, and Moana and the Moahunters didn’t just recycle the sound they heard coming from abroad. Instead, they took the conventional signifiers of global hip-hop (samples and synthesized drum beats) and added their own flair, incorporating local vernacular and occasionally rapping in te reo Māori (the native language). A small group of artists later added Polynesian drums and acoustic guitars, adding their own cultural identity to the rapidly expanding hip-hop ecosystem. The result was music that was undeniably different from anything being made in the outer boroughs of New York or on the streets of South Central Los Angeles.

What they did share with their American peers was their isolation from the mainstream music industry. The artists monopolizing radio and television airtime were overwhelmingly white, came from affluent neighborhoods, and didn’t have to prove their authenticity because they had guitars and played in the local pub. It wasn’t until the mid ‘90s that a handful of hip-hop artists began enjoying some semblance of commercial success—3 The Hard Way’s “Hip Hop Holiday” was a number-one smash in 1994 (though they were later sued by British band 10cc and lost all royalties from the song). In 1997, OMC scored a global hit with “How Bizarre,” and DLT dominated the New Zealand Music Awards with his anti-nuclear protest song “Chains.” King Kapisi became the first hip-hop artist to win the coveted Silver Scroll Award in 1999 for his single “Reverse Resistance” (the award is the New Zealand equivalent of Britain’s Mercury Prize).

Their success opened the door for a thriving subculture in South Auckland, an urban area in New Zealand’s largest city that is home to the world’s largest population of Polynesian people. New Zealand music historian Gareth Shute, who in 2004 wrote the book Hip Hop Music in Aotearoa, describes the area as the “true home of Polynesian rap music.” He notes the demographic similarities to parts of South L.A. and Brooklyn, with a large concentration of working-class people from the diaspora, as one of the reasons why hip-hop resonated so strongly with young Polynesians.

The heightened visibility of groups such as Deceptikonz, Nesian Mystik, and artists like King Kapisi, Dei Hamo, and Christchurch rapper Scribe at the turn of the new millennium provided a blueprint for the next generation, who today make up the region’s extensive hip-hop scene. “King Kapisi was one of the first Polynesian rappers I heard who incorporated Samoan in his raps, which influenced me to fuse my Polynesian culture with the music I made,” says Albert Purcell, one half of Auckland duo Church & AP. Auckland rapper Melodownz had a similar experience. “When I was about 11, I discovered Scribe and was instantly obsessed,” he says. “There’s this song called ‘Remember’ where he tells a vivid story. It made me feel emotional, and as a kid I don’t think any other New Zealand song made me feel that way. That [song] introduced me to the art of storytelling and has had an impact on how I tell stories in my raps.”

Here are six hip-hop artists fusing the unique sounds of the Pacific with American rap music.

Melodownz

Rapper Bronson Price grew up in Avondale, a neighborhood in West Auckland that in recent years has become a mecca for local hip-hop. His Avontales EP details what it was like growing up in the area, with its strip of Chinese, South Asian, and Polynesian takeaway shops and deep community roots. The locale provides the backdrop for Price’s conversational songs, which describe domestic abuse, encounters with former school mates, and the aggressive approach of local police officers to those living on the margins. Price is a vibrant storyteller; it’s a skill he developed in high school and later sharpened with his cousins and other rappers in the local community. “We had speeches in English class, and for mine I made the whole thing rhyme,” he says. “From then on, I was busting freestyles with my friends at lunchtime, then started having rap battles at parties. One day, I came home and my cousin had downloaded a recording program on the family desktop computer. We used a gaming headset for the microphone and started making songs.”

Coco Solid

For more than a decade, Coco Solid has presented an alternative version of Pacifika hip-hop, with a sound characterized by a web of midi synths, techno, and booty bass. Her decision to steer clear of existing structures and build her own path has resulted in a style of hip-hop that few have replicated. “I’ve had a strange but pretty cool trajectory,” she says. “It’s a narrative marked by constant realizations of independence and creative emancipation. It’s also been about building my own thriving music community, instead of trying to assimilate into the communities already formed. I’ve always been very DIY and resistant to the limited rap templates I was shown.” She is also the driving force behind a recent project called Equalise My Vocals, aimed at elevating the voices of other female and non-binary artists in Aotearoa. “I think it’s part of how I’m hard-wired. The Māori proverbs are all anchored in the sentiment of ‘a tatou taonga mo apopo,’” she says. “You have to cultivate and support the leaders of tomorrow so the right shit is still being challenged when you’re gone.”

Rizván

“Polynesian history was culturally passed on orally, with a few exceptions of documentation by foreigners. I’m pretty much carrying on that tradition,” explains Auckland rapper Rizván Tu’itahi. Inspired by local luminaries like King Kapisi, Ermehn, and Che Fu—some of the first rappers to incorporate Polynesian instruments and proudly rep their own local dialect—Rizván places those same elements at the forefront of his music. His “Gemini” mixtape begins with a Tongan hymn and is followed by “Phoenix,” a biographical tale of growing up in Nuku’alofa (the Tongan capital). He raps about being born in Viola Hospital and hearing his parents singing the same songs he heard while still a baby in his mother’s womb. Decades later, he’s part of a broader hip-hop family that includes the rappers Diggy Dupé and S.F.T under the Renaissance Music umbrella, and shares a cultural connection to Melodownz, Spycc, and Poetic. “Our common ground is our culture, both ethnically and musically,” he says. “Hip-hop is like our home away from home.”

Church & AP

This Auckland duo are benefactors of a community outreach program designed to nurture and encourage local youth to participate in the arts. They were mentored by Dirty (of local group Eno x Dirty), Melodownz, and Tom Scott (Homebrew/@Peace/Avantdale Bowling Club), and this past winter (summer in Aotearoa) had a breakout hit with “Ready Or Not,” which was recorded in a community center in West Auckland near AP’s childhood home. Their music displays a range of inescapably American influences, notably West Coast and Southern Rap (“Ready Or Not” samples Devin The Dude’s “What A Job” feat. Andre 3000 and Snoop Dogg), but there’s a Polynesian influence, spread thin like butter, across everything they do. “I was hearing a little bit of everything growing up, from gangsta rap to rock. I heard Scribe playing as much as I heard 2Pac, and sometimes I’d even listen to my grandmother’s Samoan pop music, such as The Five Stars and Jamoa Jam,” says AP. “Being both Samoan and Tongan, I get to draw [upon] a lot of different cultural aspects and traditions, and apply that to my approach. Even if our music doesn’t correspond with what our elders may have listened to, at least we are honoring our roots in some form.”

Tei

Louise Burling doesn’t like to label her music. “I prefer to be genre-fluid and have the space to change and morph each track, depending on where the track is taking me,” she says. Built entirely on impulse, her music blends the sensual qualities of R&B with the meditative elements of rap music. Burling grew up in Westmere, a stone’s throw away from Grey Lynn which, in the last 20 years, has gone from being a large Polynesian enclave to one of Downtown Auckland’s most expensive neighborhoods. But before it was gentrified, which resulted in the displacement of a large portion of the Polynesian community, Burling says it was her gateway into hip-hop. “I’ve just always been surrounded by it. Our area had a lot of state housing, and because of the socio-economic history of hip-hop, I grew up with kids on my block who lived and breathed it.” Her biggest musical influence however, is the R&B/hip-hop singer Tinashe. “She was the first artist to introduce me to genre-fluidity, and she was also the first artist that I had heard of that produced, recorded and mixed her own tracks.”

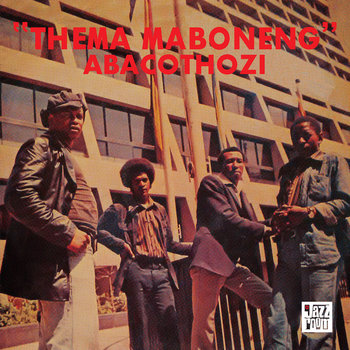

Poetik

Ventry Parker was born in New Zealand, grew up in Apia (the Samoan capital), and spent five years in Australia. The rest of his siblings ended up in Southern California, so it’s no surprise to hear traces of West Coast rap and G-funk in his distinctly Polynesian rap music. “Most Samoans abroad live in California and Utah, where everything is just West Coast style. So those were the tapes and CDs that they brought back home [to Samoa],” he recently told New Zealand website The Spinoff. “The lifestyle in L.A. and Long Beach is all about coasting—that vibe where it’s sunny all year round and you have the cars and the girls out. That’s like the island life, too.” Poetik’s music provides a history lesson in Samoan culture. He shouts out local landmarks and reps the “685” (the Samoan country code), attacks the British monarchy for their role in sending Polynesian people (using a coercive tactic known as Blackbriding) to work in Sugar Cane fields in Australia, and addresses the role of religion and family in the wider community.