Paul Ravenwood is a living piece of American history, a man with a connection to both turn of the century America and the kind of small Appalachian farming communities that feel like the stuff of folklore. He’s a collector of Americana, too, both popular and fringe. But he’s also someone who has suffered great loss, and at a tremendous price. His deeply-personal music, born out of pain, perseverance and self-reliance, are the things that sustain him.

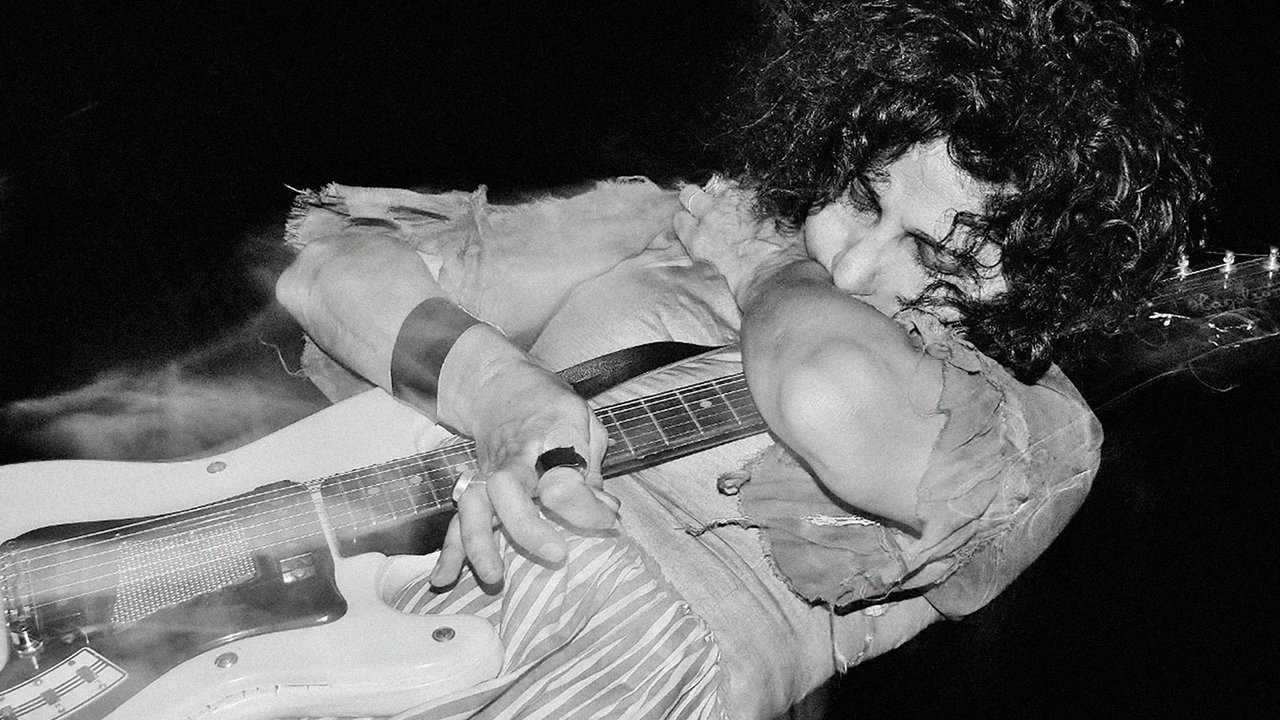

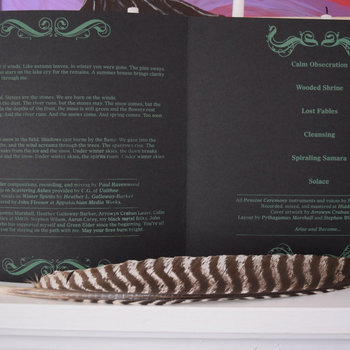

In August, he released two albums. One, with Twilight Fauna, his folk black metal project, is full of turbulent, emotional songwriting. The other is under the name Green Elder, his traditional American folk project, and is a split EP with the band Pensive Ceremony. Although they’re very different musically, the projects have a common core: Paul, and his life experience. It’s through music that he’s able to express, cope with, and share his experiences. Throughout both records themes of religion, particularly Pentecostalism and the practice of snake-handling, shape the core of the lyrics. Those themes have played an important role in making Paul who he is and, he’s forthright and candid about all of them.

We sat down with Paul to talk about the America in which he grew up, his connection to the soil of the Appalachian mountains, and the family tragedies that befell him at a young age.

Vinyl LP

Where is the Appalachian town in which you were born?

I was born in a ‘holler,’ called Newport, in East Tennessee. I no longer live in the same town, but I’m still in the Appalachian mountains, a few hours north. I consider the mountains here my true home. At this point, it would be hard to imagine myself anywhere else.

Excuse my Yankee ignorance but: What’s a ‘holler’?

Geographically, a holler is a valley between two ridges. When folks settled this area initially, a lot of times families would group their houses together in the same place. Over time, that kind of led to the insular nature of mountain communities. A lot of hollers are named after the folks that live there, and a lot of the older communities out in the mountains still operate like this. Or at least, there are remnants of this kind of thing still around. The community I grew up in had easily less than 1000 people, and that was stretched over a pretty large area. To give you an idea how isolated it was: the nearest neighbor we had to the farm was maybe a mile away. Hell, I was 21 before I lived close enough to anywhere that I could actually have pizza delivered. It changes your outlook on the world when you grow up in a place like that. It left a lasting impact.

Did you come from a large family? Your background seems to suggest that.

It’s fairly large. My mother was the youngest of 11 children—she and most of her siblings are no longer living. This can be a hard place to live, and it can take its toll—especially when things like access to proper medical care [are] still an issue in the more rural places. But since I’ve moved out of that community, I don’t really have much contact with those that still live there. In a lot of ways, once you move out of an insular community like that, you’re sort of seen as an outsider from then on. At least, that’s been my experience.

Were you close with your family?

Definitely with my parents. We had a small farm in the mountains. It was isolated by most standards, but also located in an amazing place, nature-wise. I grew up there, playing in the woods—hunting, fishing, that kind of thing. When I was young, I think I assumed everyone had this experience. Then, I moved away for college, and realized that isn’t the case with a lot of folks. As I’ve grown older, I’ve learned to appreciate the self-sufficiency and appreciation for nature that I got from growing up that way.

I assume that a family in that type of situation would be pretty religious. Were you raised in the church?

I grew up attending a small Baptist church that my family had attended probably since they first came here in 1850. It was a few local families. Maybe around 70 people would attend services on a good day. It was very much an ‘old time religion’ kind of deal. People spoke in tongues, would get filled with the Holy Spirit, and get up and run around screaming and yelling. My family was very active in the church—I’m sure some of them still are. I stopped attending in my late teens, but I did go back a few years ago for my grandmother’s funeral. The place hadn’t changed a bit. Even at the funeral, they preached fire and brimstone. It was like being transported back in time to when I was a kid. Incredibly surreal. Here is a picture of my folks taken at that same church. My grandmother is the girl on the very left.

Vinyl LP

Was the first time you left that area to attend college?

I moved a few hours north to a city, but I was still in the mountains. College was really the thing that spurred me to make a change in terms of where I lived, and it opened my eyes to the world outside the sphere of my small town. I ended up spending way too long in college, actually. I think I wanted to soak up as much information as I could. It was the first time I had the realization that a lot of people didn’t really have the life experiences I had growing up. In some ways, that may have planted the seed in my head that some of my stories need to be told.

I’m aware that you lost your parents at a young age. Can you talk about that a bit?

When I was in my mid 20s, I found out my mother was diagnosed with a terminal illness. She didn’t have health insurance, so by the time they knew something was wrong, it was way too late. She was given a few months, and over the course of three years, I watched her health slowly deteriorate until she eventually lost the battle. Less than a year later, before I could even process that, I got the call that my dad’s body had been found on the family farm.

I can’t even imagine. That must have been horrible.

It’s indescribable, really. There are certain things in life that, after you go through them, you’ll never be the same. We all have these things in our life—people, places, even music—that we cling to when bad things happen. They’re things that anchor you and bring you comfort, things you tell yourself will always be there. Over the course of about a year and a half, I had those ripped away, one after another. I’m lucky enough to have had a few very close people that helped pull me through that. Between those people and creating music, somehow I was able to keep moving forward. It’s something I still deal with everyday, on some level. I’m not sure if you can ever really put something like that completely behind you—and maybe it’s better that you don’t try to. Loss is a good reminder of what’s really important in life.

Is that what inspired your music?

My music is deeply personal. Even the tracks that seem to be about someone else reflect my own struggles in some way. A lot of the themes of my work are related to loss and death, and those weren’t chosen by accident. It’s such a part of me. It’s in every note that I write. I want my music to be an honest reflection of my own life. So it’s all in there, both the good and the bad. Life has ups and downs, and I want my music to be the same—to capture that as much as I can. So I try not to dwell on it too much from a musical perspective. Still, there are certain songs that I can’t bring myself to go back and listen to, because they’re tied to very specific points of time that are still too painful to revisit.

Vinyl LP

Is that therapeutic in any way for you, or is it just painful?

Being able to write music and create is my own way of processing my own struggles, but I don’t want to limit it by saying that’s the sole purpose. It’s also a way of telling stories that I think are important, of celebrating triumphs and things that I love, a way to share pieces of myself that I couldn’t put into words otherwise. Music is one of the most important things in my life for many reasons.

What happened with the farm when your parents passed away?

After my parents passed, the farm fell to me. It was in pretty bad shape, to be honest. It needed a lot of upkeep. By that time, I was living over an hour away for work, so I made the decision to sell. Even though I had no plans to move back, suddenly saying a final goodbye to the place you grew up felt like another loss. But it had to be done. There are some things in life we all try desperately to hold on to forever, but the reality is that most things in life are much more fleeting than we want to believe.

You mentioned you still live in the Appalachian area. Why did you choose that?

When I moved away for college, I ended up getting a job in the area and stayed because I love it here. My house is a few minutes from the Appalachian Trail; there are endless wild places to explore here.

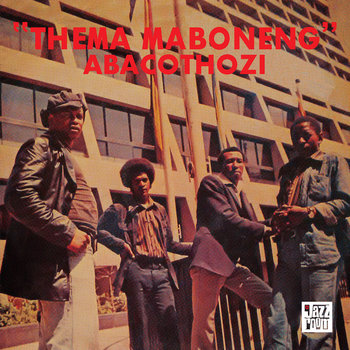

Your album deals heavily—almost exclusively, actually—with snake handling. How did that enter your life?

There were a couple churches that practiced it in my hometown. I was always fascinated by it, but never saw it in person. It’s amazing to me that people would hold a belief strong enough that they’re willing to put their lives in danger. It was known throughout the community that some folks practiced it, and everyone knew which churches did. But if you weren’t part of that, it was seen as this dangerous thing you didn’t go to, unless you went to that church. I used to drive past them when I was young and wonder what it was like to experience what happens inside. Every Sunday, people facing their own mortality in a life-and-death struggle. That would have to have a life-changing impact on how you saw the world.

Vinyl LP

How does the snake handling belief system differ from what you grew up around?

Their belief system and the very traditional church I grew up in are very similar. When I started doing serious research for the album, I was watching and listening to a lot of footage from snake handling services, and I quickly realized it sounded exactly like what I grew up with. The services were very much the same, except in the church where I grew up, snakes weren’t involved. But other thing—like getting the Holy Spirit and dancing or yelling, speaking in tongues, laying on of hands and praying for someone—those kinds of things were exactly the same. I remember, shortly after my mom got sick, going to visit the farm, and there was a preacher and a few other people there anointing her head with oil and praying for healing. Whenever I’m writing about the experiences of others, it’s always a concern of mine that the songs won’t contain the same kind of personal reflection that I want in my songs. But in this case, in hearing [snake handlers] speak about their beliefs and reading interviews with folks that practice that kind of religion, it became very clear early in the process that their story and mine felt intertwined somehow. Maybe it’s because of how I grew up, and us being from the same area, that’s a hard thing to quantify. But this release feels like it contains as much of me as it does them.

Throughout your research, have you found any merit to the belief system ascribed by snake handlers?

There would have to be merit to those that practice it, otherwise it wouldn’t persist. People wouldn’t put their lives in danger if that wasn’t the case. In terms of myself handling snakes, I don’t think I would get anything from it, but I don’t share their beliefs. I know in a few states there has been some controversy in terms of the legality of it. But as long as they aren’t putting others in danger, in my opinion they should be left to practice whatever beliefs they’d like.

How does all of that connect, literally, to the music?

I tried to approach this topic in the most respectful way possible. When I decided to take this on, I started by doing a lot of research—reading interviews, watching footage of church services, things like that. In the end, I decided to write the lyrics based on [the participants’] own words. I tried to hold as closely as possible to that. Also, with the similarities to the church I attended growing up, I was familiar with the format of how their services flowed. I tried to structure the album like one of their church services. If you listen from start to finish, I hope it has that kind of feel to it. The physical packaging for the record is an extension of that as well. This has taken over 2 years to put together. I hope it will be a unique experience for all involved.

You have a pretty deep connection to the land, and you seem open to exploring religions. How would you classify your belief system?

I don’t really assign my belief system any particular designation. It’s similar to classifying my music. If I say I play black metal, suddenly people have expectations. Suddenly, there are all these rules as far as what I can and can’t do, or how I should sound, or what I should believe. I’m much more of the belief that people should figure out what they believe as individuals based on their own experiences. For me, I feel a close kinship with the earth—especially the mountains that are my home. I’m at peace when I’m close to nature. It feels like that’s where I should be, and I find great meaning in that. Maybe some would classify me as pagan. I’ll let people call that what they will.

—Zachary Goldsmith