When the prolific metal guitarist Colin Marston was about 10, a ride to band practice changed his life.

His bandmate’s music-loving father, himself a longtime amateur bassist, had picked them up from school. While driving his charges to rehearsal, he put on some King Crimson, the prog band that brought to rock music a new level of brain-splitting intricacy. Marston, who’d never heard the band before, was floored; before long, he was tracing his own way through Crimson’s catalog. He was especially intrigued by something else he’d never heard before—the Chapman Stick, a wide piece of wood with 10 or 12 strings that were tapped more than strummed, producing a hybridized bass-and-guitar tone that sounded as alien as the instrument itself looked.

By the time Marston saw a reunited King Crimson live, one of their two Chapman Stick players, Trey Gunn, had already switched to something even more exotic: the Warr guitar—essentially, the Chapman Stick on audiovisual steroids. For listeners averse to guitar, Warr is the stuff of nightmares, the mutant villain in a horror musical with an apt name. For budding young players, on the other hand, it’s the stuff of grandiose musical fantasies and dreams of shredding to fan-packed stadiums

Its inventor, Mark Warr, was in fact inspired by the Chapman Stick and, beginning in the early ’90s, ran wild with its design. Warr guitars stretch 7-to-14 strings between an elaborate and often dramatic guitar body, and its headstock, which runs along a neck as wide as a young tree trunk. The strings are a mix of electric guitar and bass strings, giving musicians a very broad octave range and allowing them to play guitar and bass, lead and rhythm all at once. Thanks to its dual outputs, the guitar can produce at least two distinctive voicings at once, too—Marston actually uses three amps.

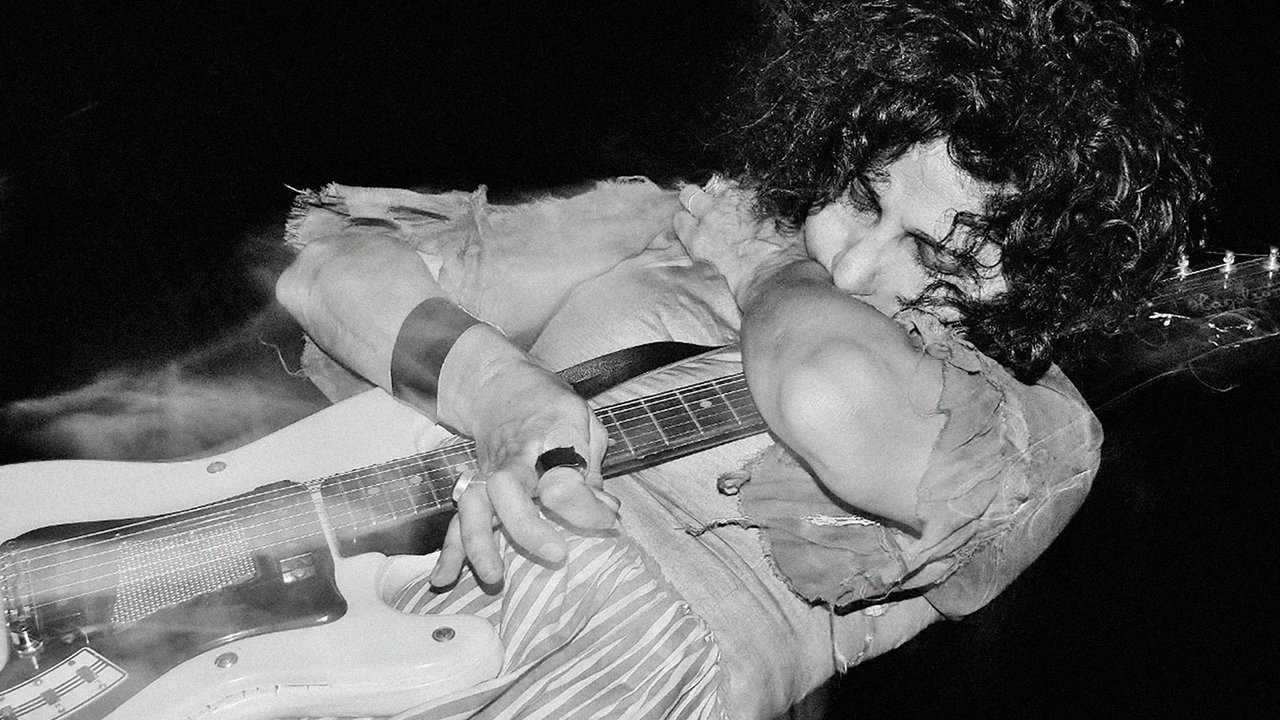

“The Warr guitar is in this weird nether region between bass and guitar, but it’s kind of like a keyboard, too. It doesn’t have a traditional role in a band,” says Marston. He plays the Warr in three of the strangest, most electrifying metal acts going: Krallice, Behold the Arctopus, and his solo project, Indricothere.

“You have all this flexibility about where you can play a musical idea on the instrument—and that will have a big impact on how it sounds,” he says.

If the Warr guitar seems absurd, that’s because it is; players often thrive on a sense of ridiculousness, on the warped musical reality that holding 12 or 14 strings fed through multiple amps at the same time can bring. From Ricky Wade covering TOTO to Spingere’s oddball industrial throb, music made with the Warr guitar seems to embrace the extreme, to push into weird new wormholes. As the company’s FAQ sheet concludes, “Am I crazy? It’s possible.”

The world of “touch instruments” like the Chapman Stick and the Warr guitar, which have spawned multiple spinoffs, is surprisingly large. But the Warr guitar scene itself is small, and maybe getting smaller. Each fully customizable instrument might cost $5,000 and take a year to make—Marston got his first 12-string Warr at a deep discount by attending a guitar summer camp at the age of 15, while the second was a gift from Warr himself. And late last decade, Warr announced he had colon cancer and would not be taking new orders for the foreseeable future.

Those conditions—high price, long wait, and an increasingly scarce supply—don’t really foster diversity. The barriers to entry are just too high. “These instruments come from the ‘prog’ world, which is pretty damn white, male, and upper-class,” Marston quips, “all the categories known for exclusion.”

But those who do own a Warr have managed to create rather distinct takes on well-trodden genres, even folk-rock and smooth jazz. It all sounds imported from an alternate reality, serving as a reminder of how such strange instruments can reshape music as we understand it.

Behold the Arctopus

Hapeleptic Overtrove

Vinyl LP, T-Shirt/Apparel

Behold the Arctopus have been making dizzying music for nearly two decades now—in the early days, their name included an ellipsis, and Warr guitarist Marston and traditional guitarist Mike Lerner had to program their own drums. Horrorscension, their 2012 album featuring legendary drummer Weasel Walter, was a breathless and anxious wonder, like watching a mouse trying to escape an endless maze. But the new Hapeleptic Overtrove, their second album with Jason Bauers, is one of the year’s best metal and modern classical records. Rather than the slash-and-pummel warfare of their previous LPs, the trio now moves with an angular precision that borders on delicacy.

Bauers foregoes traditional drums for bells and blocks, giving him a more interactive vocabulary for the chattering strings that surround him. During “Telepathy Apathy,” his clatter counterbalances the piercing harmonies of Marston and Lerner, as Marston uses the Warr to add subtle bass rumbles that serve as connective tissue. The lunging Warr bass notes of “Quithtion Overtrove” keep the song grounded as the guitars bounce around like free electrons. “Blessing in Disgust” has the suspense of a classic Tom & Jerry chase scene. Hapeleptic Overtrove is a testament to the compositional imagination the Warr Guitar can inspire, to writing ideas as outlandish as the instrument’s design.

Trey Gunn

Punkt 1

Trey Gunn is the great apostle of the Warr guitar. He played it for a decade in one of the world’s most proudly byzantine rock bands, King Crimson, and he has anchored a dozen-plus projects with the instrument since. You can watch him practice Crimson’s “Schizoid Man” on his Warr (“The Beast,” he dubs it) in a Polish hotel room, and he proselytizes its gospel in print. Gunn relentlessly pursues new approaches to the instrument, too, as recently as the start of COVID-19 quarantine at his home in Seattle. The 10-track Punkt 1 is a series of improvisations on a “prepared Warr,” recalling the thwacks and pops of Derek Bailey and the rhythmic intrigue of Eugene Chadbourne. It alternately sounds as if Gunn is playing a banjo, a synthesizer, a taut rubber band, or a drumkit of hubcaps and buckets. The design of the Warr—all those strings, all those outputs—gives it incredible textural possibilities. Gunn continues to find them.

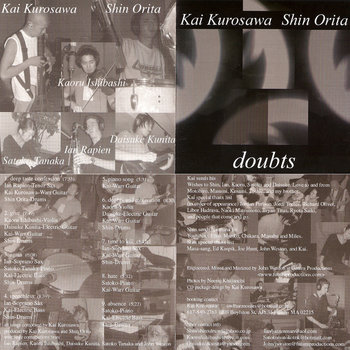

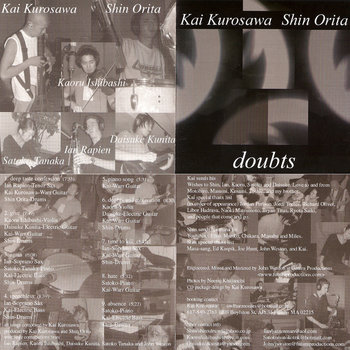

Kai Kurosawa & Shin Orita

Doubts

Compact Disc (CD)

These days, Kai Kurosawa can’t be bothered with the 14-string limit of the Warr guitar. He plays the Kūbo, a 15-stringer he helped craft, and a 24-string behemoth called the “Beartrax” that he also designed. But back in 2002, when Kurosawa recorded this glittering jazz album alongside drummer Shin Orita and a cast of horn players and pianists, he was still studying at Berklee and emerging as one of the Warr’s chief new acolytes..

These sophisticated pieces sometimes recall the more melodic side of ECM Records, with cascading keys and complex variations, or the more direct side of jazz fusion. But the most beautiful moments come from a pensive and patient Kurosawa, when he sits with the Warr and teases out gorgeous harmonies that summon Bill Frisell or even the sentimental moods of Grant Green. His introduction to “Give” is a moment of pure bliss, while the bittersweet lines he taps to start “Piano Song” feel like staring into the middle distance on a bright fall day. Kurosawa renders some of the most purely pretty music you will ever hear on the Warr.

Indricothere

Indricothere

Colin Marston has made several records as Indricothere during the last decade or so, releasing three albums under that name in the last four months alone. (The latest, Tedium Torpor Stasis, is a battering ram, while XI.. is a massive digest of slow-motion synth work.) But his 2007 debut under that name—as electrifying as the rainbow wheels on its cover, if not quite as powerful as the dinosaur at the center—still lands with an unmatched urgency. During opener “II,” he creates a sudden sense of vertigo by interrupting fast-fingered runs and thundering bass parts with slashes of silence. And for “III,” Marston uses the Warr to create a spiraling series of notes above the black metal onslaught below. Thrilling and overwhelming, Indricothere’s beginnings bask in the inspiration Marston found while still making sense of the Warr—and where he might soon follow all those strings.

Jim Wright’s The Fuzzy Logic Boptet

Playing Favorites

Compact Disc (CD)

It’s surprising that there’s not more traditional jazz—bebop, especially—played on the Warr guitar, given the instrument’s range of voice and octaves and its tonal clarity. What does exist tends to be more experimental and aggressive, perhaps prompted by the instrument’s seemingly bellicose name and weaponized size. The Chapman Stick, invented almost half a century ago by a jazz guitarist, also had a considerable time and marketing advantage in the field.

But there are a few artists using the instrument for these ends, like the intricate solo stuff of Randy Strom or The Fuzzy Logic Boptet, led by his contemporary, Jim Wright. On Playing Favorites, Wright leads a capable quartet (immortalized by that, uhh, incredible cover) through a chiming rendition of Thelonious Monk’s “Straight, No Chaser” and a wonderfully restrained take on Wayne Shorter’s “Footprints.” During the wispy ensemble “Gate Array,” Wright steps out for a rare shrieking solo, maintaining the bassline with one hand as he briefly conjures, say, Van Halen with the other.

E.A.R.

A æ u å æ ø i æ å, æ i å u å æ ø i æ å?

E.A.R. are an unlikely Spanish trio founded by musician Efrén Lopez, featuring death metal drummer and percussion polyglot Adrián Perales as well as piano teacher and Warr guitarist Raül Bonell. López has explored the world in search of intriguing folk instruments and, in the process, become a modern hurdy-gurdy authority. They somehow funnel all that into their sprawling 2019 debut, one of the most doggedly ambitious and esoteric records you may ever hear. Named for a Danish word game, the guest-heavy double-album includes tracks in eight languages and stretches stylistically from djent menace to traditional Balkan dances, pastoral hymns, and psychedelic drones.

Bonell bends the Warr to every one of these situations, whether playing simple basslines, stepping to the middle with lumbering metal riffs, or stepping out for pyrotechnic-like solos. He even covers touch guitar icon (and designer) Markus Reuter here, tapping out the notes of “Prelude” with such care it suggests a harpsichord. These 19 tracks are a testament not only to the Warr’s adaptability but also to the sort of gloriously absurd conceits it can motivate.