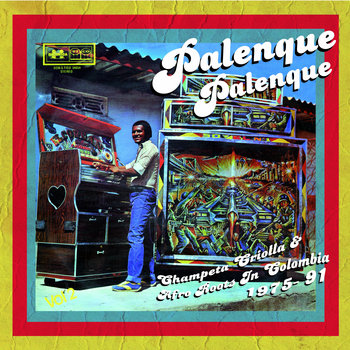

When filmmaker and DJ Lucas Silva started Palenque Records in 1996, he had one goal: To uplift champeta—a Colombian re-interpretation of Nigerian highlife, Congolese soukous, and afrobeat, played in the marginalized districts of Cartagena through giant colorful sound systems known as “picós.” Dazzled by the sounds of the second wave of champeta in the ‘90s, known as champeta criolla, Silva took it upon himself to find and record the legendary musicians who birthed the genre.

“Back in the ’90s, champeta was very underground,” says Silva, “it was seen as lower-class, it was an Afro-Colombian genre, and most people wanted nothing to do with it.” Silva himself did not gain a deeper appreciation for the genre until after meeting musician Justo Valdez, vocalist for the group Son Palenque, who was selling sunglasses to tourists on the beaches of Bocagrande at the time. “That day, Justo sang me some of his hits, a cappella, and each of his songs had something new to me,” remembers Silva, “Justo told me that this music came from the soukous played by Congolese musicians living in Paris.” For Silva, this meeting sealed his decision to help amplify champeta’s unique sound. “I felt that with champeta came a new world of musical sonorities I never heard before,” he explains, “[it had] frenzied, trance-like guitars, metaphysical harmonies, hip-bending bass lines, and drum breaks that could disarm anyone,” he says. In the music’s African roots, Silva found “groundbreaking liberty and harmonic creativity.”

To investigate champeta’s origins, Silva traveled to San Basilio de Palenque, a small village in the foothills of the Montes de Maria. Palenque, from which Silva’s record label took its name, holds an invaluable place in Latin America as the first town established by enslaved Africans who fought their way out of Cartagena. In Palenque, Silva met with the musicians of Sexteto Tabalá, a local group of farmers who mixed Palenquero (a language combining African Bantu, Spanish, and Portuguese words) and son Cubano (a Cuban style of music made up of both Spanish and African rhythms.) Despite having no experience in recording or producing, Silva felt compelled to record Sexteto Tabalá. Until that point, the group had only performed for the people in their community. “I wasn’t a music producer, I was just an avid record collector and documentary filmmaker,” recalls Silva. “But I thought if no one was doing this job, I should.” Later on, Silva would record another group from Palenque, the women of Las Alegres Ambulancias, who performed during the funeral traditions of the local religion known as Lumbalú. This record, Las Alegres Ambulancias de Palenque, would become a vital document of Palenque’s Afro-Colombian ancestral traditions. The buzz generated by these first records inspired Silva to continue collaborating and recording with other musicians such as Son Palenque, Estrellas del Caribe, and percussionist Paulino Salgado “Batata.”

Despite spending over two decades immersed in champeta, Lucas Silva is still excited by its unique sound and revolutionary potential. “Champeta is groove music, it is part of the Afro-Caribbean identity,” he says. “Champeta is also a way of living: Every week new words and styles are created.” He draws a parallel between punk music and champeta—like punk, champeta can’t be entirely defined as it’s always evolving into something new. And champeta, just like punk, can be sung by anyone who enjoys it. Crucially, champeta is living evidence of Colombia’s enormously diverse artistic expressions. “What I like the most about Palenque Records is that the music we are doing is a spiritually liberating experience,” Silva says. “Colombia is a colonialist country that we want to set free. I see music as a cultural revolution.”

Silva’s sentiment is applicable to his overall mission for Palenque Records, which is to provide a platform for Afro-Colombian artists and their important place in Colombian popular music. Through his work operating and running the label, Silva has taken a strong stance in showing the world the patrimony of Afro-Colombian music.

Here are a few highlights from the Palenque Records catalog.

Sexteto Tabalá

Clavo y Martillo

The music of Colombian “sextetos” sees its origins in the union of Palenque’s oral tradition and the Cuban rhythms that spread through the village’s sugarcane plantations. While it was never documented during the height of its popularity in the ’50s and ’60’s, the music of “sextetos” was preserved by the musical dynasties living in Palenque. “Clavo y Martillo,” edited in 1996, became the first recording of a rural “sexteto.” In it, rich vocal polyphonies blend with marímbula harmonics, backed by guitars and “pechiche,” a type of native drum used in ritual music.

Las Alegres Ambulancias

Música funeraria de Palenque

Whenever a villager dies in Palenque, the women in Las Alegres Ambulancias are called to sing during the nine-day ceremonial wake, part of the local religion known as Lumbalú. The record’s opening track, “La Maldita Vieja,” is a perfect example of the spirit of these “bullerengue” singers whose laughter and celebration is equal parts salacious and earth-shattering. “We have named this band ‘The Jolly Ambulances’ because we are jolly old women; we drink rum, and sing, and liven up funeral wakes. It is the art of mourning the dead to please our ancestors,” said bandleader Graciela Salgado during the making of the album, back in 1999.

Batata y su Rumba Palenquera

Radio Bakongo

“This is the story of my land, of the African blood,” announces Paulino Salgado on “Batata,” taken from Radio Bakongo, the only album the legendary percussionist ever recorded. The addition of Congolese guitarists Dally Kimoko and Rigo Star to Radio Bakong forges a musical bridge between Salgado and his ancestors in Congo. Horn arrangements, upbeat rhythms, and repeated backing vocals yield the perfect balance between afrobeat, cumbia, and “soukous.”

Son Palenque

Afrocolombian Sound Modernizers

Going back to its inception in the ‘80s, the seven-piece band Son Palenque represents the sacred union of African rhythms and psychedelia at its finest. Through its many incarnations, the band brought their irresistible groove to local parties in Cartagena, building a reputation around their oftentimes comical and endearing songs. Tracks like “El Sapo,” and “Azuca y Limón” work as perfect introductions to the band’s catalog: Lighthearted lyrics over non-stop drum beats that can make even the most apathetic “gringo” get up and move their feet.

Abelardo Carbono

“Zelo Zelo”

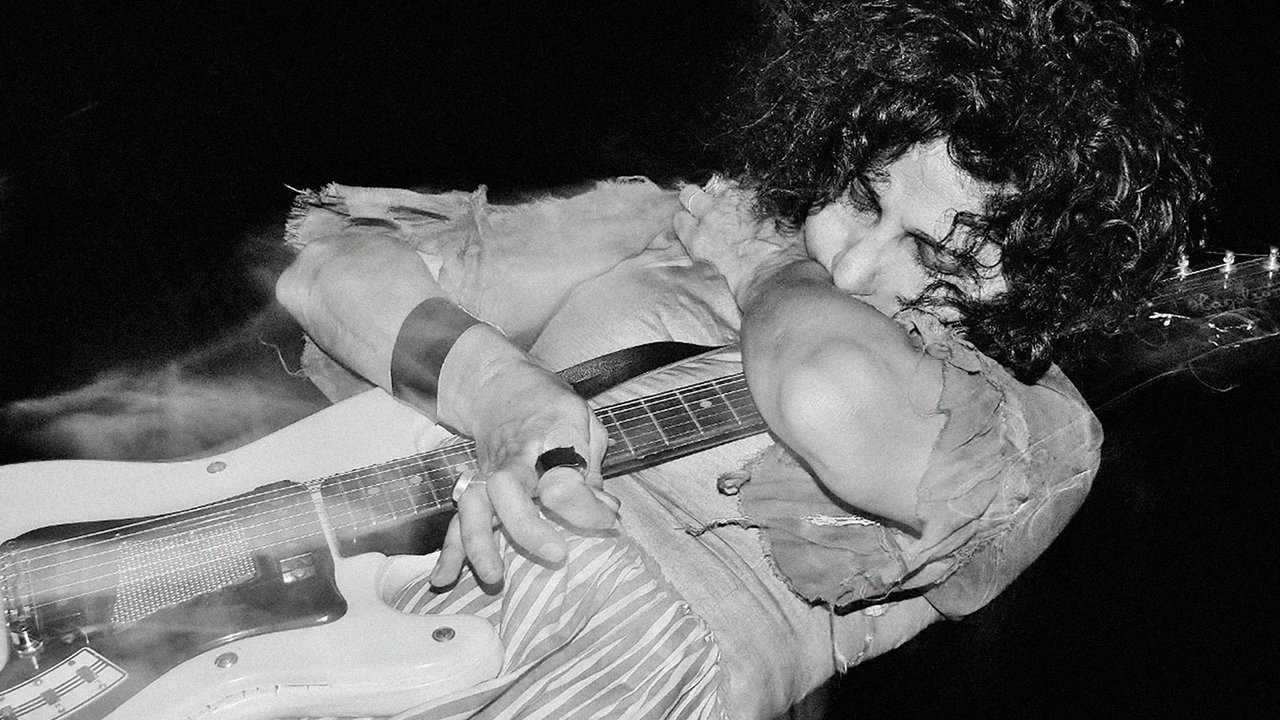

Originally recorded in the ‘80s for the defunct Felito Records, “Zelo Zelo” is a timeless hit from guitar player and godfather of champeta, Abelardo Carbono. Carbono started playing at age eight and formed a band with his brothers, Jafeth and Abel. Their signature sound consists of delicate harmonies surfing over Carbono’s masterful guitar playing. “Abelardo started playing in the ‘70s,” says Silva, “from listening and imitating Congolese guitars. He was the first person in the Caribbean coast to play African style-guitar rhythms.” The re-issue of Carbono’s records in Europe would spike a renewed interest in his career, allowing him to tour and record again.

Gualajo

“El Patakore”

“José Antonio Torres Solís was the king of the marimba on the Pacific coast,” says Silva. “We recorded this track when he was seventy-three. He was a well-known character, and he’d always win every marimba competition in Colombia.” A master player and teacher of the indigenous instrument “marimba de chonta,” Gualajo represented the music of the South Pacific Colombian coast, known as “currulao.” “El Patakore” is the only track Gualajo would record with Palenque as the musician passed away in 2018.

Faraón Bantu y ChampetaMan

Vol. 3 Futuro Ancestral!

In Silva’s words, Faraón Bantu is “the soundsystem of Palenque Records,” a creative hub for sonic explorations, where champeta classics are remixed and reimagined by guest DJs and producers. Along with these collaborators, Silva manages to successfully adapt mournful, oftentimes bare tunes, into layered and vibrant compositions ready for the dancefloor. Standout tracks “El Machetazo” and “Vacile en Nueva Colombia,” remixed by underground DJ Rata Piano bring out the best of the “guarapo” subgenre—African tracks remixed by Colombian DJs.