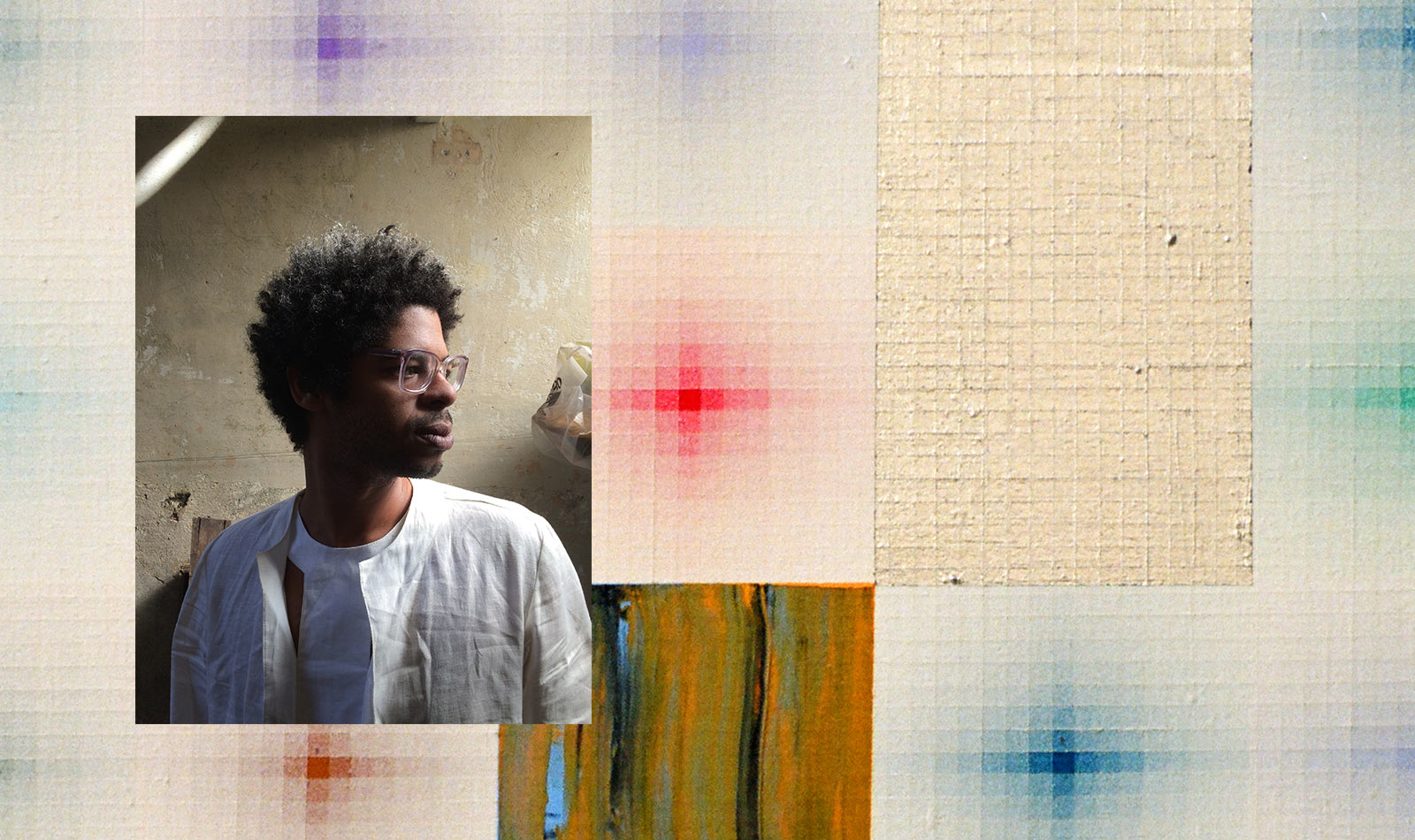

The best way to understand the work of Leonardo Campelo Gonçalves, aka Negro Leo, is by listening to him. That, of course, involves listening to his music. An ever-growing body of politically and musically provocative albums whose sounds run the gamut from no wave to música popular brasileira (MPB), his discography touches upon subjects like Brazilian working-class culture and liberation theology. But listening to Gonçalves speak is an informative experience in its own right, like listening to your favorite professor ramble after class, smoldering joint in hand. His musings on music, politics, and his career were enough to warrant a 2020 documentary by Paula Gaitán, sustaining interest over two and a half hours with his words alone.

“Fighting for freedom is part of my work,” he says in that film. Under the current Bolsonaro regime, which has eroded labor rights and unleashed racist police violence, Gonçalves’s work is all the more relevant. A sociologist by training and musician by choice, his thoughtful approach to melding art and politics is evident in how he talks about his music. But his recalcitrant spirit has earlier origins. He laughs as he recounts an episode from his childhood in which a shop owner thought he was stealing: “He started shouting at me and my father just punched him. It was the first time I saw that we can do some kind of justice by our own.”

Though some might object to this sort of reprisal, Gonçalves’s anecdote reflects a decades-long history of liberatory struggle that emerged in Brazil in response to the violent legacies of Portuguese colonialism and a U.S.-backed military coup. Filmmaker Glauber Rocha (and, incidentally, Gonçalves’s father-in-law as he is married to fellow experimentalist Ava Rocha) once asserted that “the aesthetics of violence are revolutionary rather than primitive” in his manifesto for the Cinema Novo movement. You might hear that violence made sonic in the noise of CAC CAC CAC or the dissonance of Ideal Primitivo. Conversely, Gonçalves’s poppier projects like Água Batizada and Action Lekking draw from the experimental verve and sardonic wit of tropicália and Vanguarda Paulista. “I was interested in the Brazilian tradition from Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil to Arrigo Barnabé and Itamar Assumpção,” he says.

While the tradition of political art in Brazil is an essential component of Gonçalves’s musical syncretism, he takes inspiration from all sorts of places. He grew up on a healthy diet of samba from his father and Motown from his mother; discovered prog as a teenager (which is ironically what initially brought him to Os Mutantes); had his brain rewired by bebop; and stoked his political flame through Chile’s Víctor Jara and Violeta Parra. But his experiences with people perhaps shaped him the most. “I always liked myths. The words of Levi-Strauss on myths from South America, they had got me,” he remembers. As a university student, he wandered through Brazil’s interior to research indigenous mythology, exploring how culture adapted to material conditions. Later, while starting his musical career in Rio in the early 2010s, he cut his teeth performing with the Quintavant crew at Audio Rebel. Concurrently, he frequented the favela to re-up on grass and partake in the bodily dynamism of funk carioca and its hyperactive younger brother, funk 150 bpm. “I had the university, I had my friends from music, and I had my friends from favelas. It was an environment where I grew up, learning, listening to that music,” says Gonçalves.

It goes without saying that the aforementioned genres—tropicália, funk carioca, etc.—are indebted to Afro-Brazilian innovation. Even though he’s Black, however, Gonçalves is careful not to appropriate the marginal sounds of the favela. “I was not interested in doing that kind of music [funk carioca],” he says, “because, to me, it seemed that they created that. I [felt] like if I do something like this, I’m stealing.” Now based in São Paulo, he’s been looking to his own roots in the northeastern state of Maranhão for his next project. Though nordestinos are often subject to classist and racist discrimination, the region has also historically been culturally generative, if the emergence of Tropicalia in Bahia is any indication. “Being Black in Brazil it’s something that’s a part of the culture,” says Gonçalves of this duality. “You have this contribution on one hand, and on the other hand, you have the racism.”

In Maranhão specifically, bumba-meu-boi emerged in the 18th century through a combination of European, indigenous, and African musical traditions. A party staged in the streets, bumba-meu-boi is both a form of social criticism and collective joy. “People that go to dance, they also have instruments to play. It’s amazing,” says Gonçalves. “I wanna work with this traditional stuff in order to produce [modern music].”

Ironically, this turn to his roots was inspired by a trip farther east. In 2019, he flew to Beijing with Ava Rocha to perform and record alongside Chinese artists, including SVBKVLT’s 33EMYBW (Wu Shanmin) and GOOOOOSE (Han Han), Li Jianhong, and Bayandalai. Because Han could speak English, they became fast friends. “He took me to a lot of places, like ALL in Shanghai, and unveiled a different world for me, of electronic music,” he says. “Not that I wasn’t already into this world at all, but it was really fresh their [Han and Wu’s] approach. Things started to change after this meeting.” Han and Wu’s DONG project, which samples traditional choral singing from China’s Dong minority and reworks it for an electronic context, was a direct inspiration for Gonçalves’s forthcoming album.

Fortuitous encounters like these have fallen into his lap over the past decade. AI researcher and Google whistleblower Timnit Gebru once wrote to him encouragingly after listening to a track he named after her (“She used, not Google translate, but I think a better translator”). Paal Nilssen-Love once tapped him to perform together in Denmark in 2021. (“I hadn’t played electric guitar for five years!” he laughs.) And while it was perhaps not the recognition he’d wanted, Tortoise’s Jeff Parker once did a spit-take after mishearing the name of Gonçalves’ early band Baby Hitler (“‘Baby Hitter’ is so much worse than ‘Baby Hitler’”), which led to the name of the final track on their debut album. “I’ve been meeting a lot of people around the world and playing,” he marvels. “I have this opportunity, and it’s really good.”

Like Brazil’s syncretic religions of Candomblé and Umbanda, Gonçalves’s body of work is a unique amalgamation that reflects his country’s hybridity and sociopolitical history. Rather than exhibiting a virtuosic musicality, his artistry lies in his ability to organize the overflowing ideas in his brain and manifest them into sound. Both modes of music-making are important—“That’s why you can love a guy like Captain Beefheart and at the same time love a guy like Burt Bacharach,” he says—and his collaborations with others often combine the best of the two. Though some of his work has already been covered in the Daily, here’s a guide to the rest of Negro Leo’s decade-long oeuvre.

Desejo de Lacrar

Desejo de Lacrar is Gonçalves’s latest full-length release, and he’ll be taking it to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival with his band in August. One of his more sonically diverse records, his vocal delivery ranges from a haunting falsetto on the title track to a sweet MPB croon on “dança erradassa” to a staccato bark in overdrive on “absolutíssimo lacrador.”

Conceptually, too, this record remains especially relevant in the Brazilian political context. “I was interested in this slang called ‘lacrar,’ which is the verb ‘to seal’ in English,” he says. “This word could say something to me about the behavior that we developed using social media.” Specifically, he’s referring to the political polarization that social media has engendered, the sealing of discourse, and the resultant spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories. “Q surgem no vacuo das noticias/ Tudo foi feito pra gnt lacrar” (“Q arises in the vacuum of the news/ Everything was made to seal”) he sings over a warm guitar melody on “tudo foi feito pra gnt lacrar.”

QTV

Meu reino não é desse mundo vol. 1

Here, Gonçalves teams up with other Brazilian musicians to tackle the Brazilian Left’s growing animosity toward Christianity, which he sees as a critical strategic error. This record, and its sequel, are the musical form of an argument he put forth in Jacobin Brasil, contending that the Left should engage with their religious opponents with explanation, not vitriol. “Jesus said [a] lot of good stuff, you know?” he says. “We need this on the Left in Brazil to learn with the Bible.” Sonically, the first volume is prime experimental Leo, while the second volume takes the form of a somber hymn for organ and mellotron distorted through cassette tape. “We have to put religion in politics because God is not dead yet; it doesn’t matter what Nietzsche has said,” he jokes. “God is alive, and he’s loose.”

The Newspeak

Gonçalves’s first album is an emphatic statement of his signature style, full of no wave atonality and stream-of-consciousness lyricism. “I’m trying to, in this album, develop a way of playing the acoustic guitar in a slightly different approach from the traditional acoustic guitar,” he says. Instead of playing in melodic lines or virtuosic rhythms, he strips his strumming to the bones, leaving a skeleton rhythm on the title track and “Autoestudo 2.” For more in this vein of no wave and free jazz, see Ideal Primitivo, Ilhas de Calor, Niños Heroes, TARA, and Baby Hitler’s Hey Babe.

Água Batizada

Here Gonçalves attempts to, in his words, “surf the wave of Connan Mockasin.” Água Batizada is a psychedelic pop record that proves that Gonçalves isn’t all dissonance and noise. His lyrics in this record are as cryptic and poetic as ever, however: “Naquelas horas de fascínio e perseguição onde/ O corpo é vento/ O jovem voa por cima dos pés” (“In those hours of fascination and pursuit where/ The body is wind/ The young man flies over his feet”) he sings in “Marcha Para Longe” before breaking into a song that could soundtrack a cowboy chase in the Brazil Highlands. He refines these pop sensibilities in later records like Action Lekking and the aforementioned Desejo de Lacrar.

INFELIZMENTE

INFELIZMENTE is Gonçalves’s Death Grips moment. With the help of frequent collaborator Sergio Machado on drums and production, he slams together tribal drums, metallic percs, and a machine gun flow that cuts through the noise. It’s different from everything else in his discography, a promising step in a new sonic direction.