To understand Modest Mouse, you have to understand Issaquah, Washington. All of singer-songwriter Isaac Brock’s musical and existential preoccupations are attributable to Issaquah’s location on the outskirts of Seattle, just a stone’s throw from Olympia, with Interstate 90 bisecting the town. In its early days, Brock insisted that Modest Mouse was an Issaquah band to distinguish it from the Seattle grunge and Olympia twee scenes, even as their sound borrowed heavily from both. Meanwhile, the Interstate and the sprawling suburbia that it gave rise to defines Brock’s early lyrics: it is a symbol of escape, but also a guarantee that anywhere you can escape to will be pretty much the same.

Despite Modest Mouse’s ambivalence about their native surroundings, they are undoubtedly a Pacific Northwest band. Always a step outside of any particular scene, they still borrowed elements from different local sounds. Their loud/quiet dynamics come from Nirvana and other Seattle grunge bands who had, at the band’s beginnings in 1994, recently made the city the subject of national fascination. Their heart-on-sleeve earnestness is a product of Olympia’s twee-pop movement, centered around Beat Happening and K Records. Brock’s guitar heroics and lyrical cleverness are reminiscent of Up Records labelmates Built to Spill, from Boise, Idaho. Their more dissonant moments can be traced to Lync, a local post-hardcore band in the vein of Unwound.

All of these influences are filtered through Brock’s jaded stories of navigating the overbuilt, stagnant American landscape. Modest Mouse tracks are full of references to highways, parking lots, blown gaskets, and the unsavory people one is likely to meet on a Greyhound. These are songs about traveling away from home but never arriving at any particular destination. Despite all the movement that the Interstate offers, an unsettling claustrophobia reigns. “Cowboy Dan” is the exemplary Brock character, a “major player in the cowboy scene” who insists he “didn’t move to the city/ The city moved to me/ And I want out desperately.”

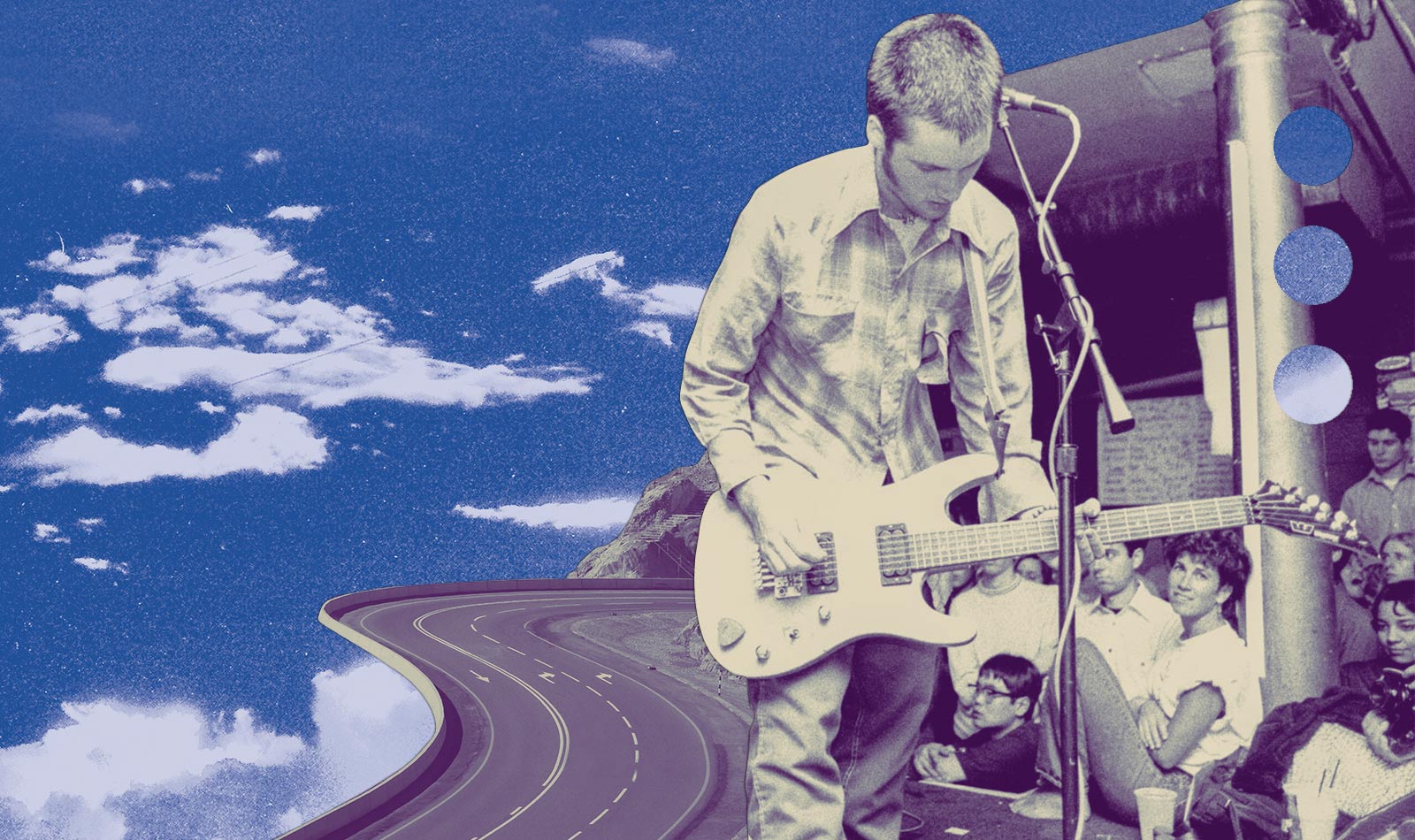

Modest Mouse would seem an unlikely group to be launched into rock stardom but for their musical inventiveness. Brock’s insights into American decline are delivered via wry aphorisms sung to undeniable melodies. His distinctive guitar style, full of harmonics and pitch bends, lends their sound a spaciousness akin to the open road. And drummer Jeremiah Green’s propulsive rolling toms, interlocking with Eric Judy’s bass, give each song a forward momentum like a car barreling down it.

Modest Mouse’s success is emblematic of a larger shift in the definition of “indie music” from an indicator of a DIY approach to a genre marker signifying a strain of guitar-based alternative rock. Across their nearly 30-year run, they have grown from a regional label to the majors, from touring in a van to headlining major music festivals. Along the way, they have left an indelible mark on indie music, influencing the generation of bands following them. The list below is a chronological accounting of that rise through their most important albums.

This Is a Long Drive for Someone with Nothing to Think About

Modest Mouse’s first album was meant to be Sad Sappy Sucker, recorded by Calvin Johnson for his K Records label in 1994. Instead, that album was shelved until 2001 and they made their proper debut with This Is a Long Drive for Someone with Nothing to Think About in 1996 on Up Records. A good thing, too, because it meant that listeners’ official introduction to the band was “Dramamine,” a fan favorite that showcases their lyrical and musical trademarks. “Traveling swallowing dramamine,” Brock sings, neatly encapsulating his fixation on motion and its discontents. Guitar harmonics bounce across the sonic field while Green’s drums chug and tumble along. Elsewhere, Long Drive takes us across the country, from the “Beach Side Property” that is “losing ground to the sea” to “Ohio,” which “is flatter than it seems.” Modest Mouse were already veteran touring musicians—their first tour began on the day that Green graduated high school—and the open road has wound its way across this album, both lyrically and sonically.

The Lonesome Crowded West

Brock’s obsession with the road was expressed with a finer brush and on a larger canvas on Modest Mouse’s second full-length The Lonesome Crowded West, released the next year. Brock bemoans the suburbanization of the West and the cheap commerce that motivates it, chanting “Soon the chain reaction started in the parking lot/ Waiting to bleed onto the big streets/ That bleed out onto the highways/ And off to other cities built to store and sell these rocks” on album highlight “Convenient Parking.” The beautiful landscape of the Pacific Northwest has become grayed out and deadened just like the interior lives of its residents “working real hard to make internet cash,” as on “Jesus Christ Was an Only Child.” After the dot-com bust and the death of malls, Brock’s diagnosis of America’s ills seems commonplace; in the late ‘90s, he seemed like a prophet preaching in the newly-paved wilderness.

Lonesome Crowded West features some of Modest Mouse’s most exciting playing. A third of the album’s tracks extend past the six-minute mark, leaving the band room for extended jams. Producer Calvin Johnson’s hands-off approach is partly responsible. For example, more than half of the 11-minute “Trucker’s Atlas” is dedicated to a guitar duel between Brock and guest Dann Gallucci caused by a standoff between band and producer. “We probably assumed that it would just get faded out, but we were enjoying playing that part,” says Brock. For his part, Johnson says that “I just tried to stay out of the way and let them have their interactions.” Whether through mutual trust or a mutual misunderstanding, the result perfectly exemplifies the song’s theme of following a winding path to an as-yet-unknown destination.

Building Nothing Out of Something

Building Nothing Out of Something is a compilation album gathering tracks from the Interstate 8 EP along with singles from 1996-’98. However, it receives nearly as much attention as official albums because it documents fan favorites from this early era that would otherwise be difficult to find. “Broke” and “Whenever You Breathe Out, I Breathe In (Positive Negative)” are studio versions of songs from the band’s demo tape Live In Sunburst, Montana. Some tracks, like “Interstate 8,” about an infinite figure-8-shaped highway, would fit on either of the first proper albums. Others, like “Never Ending Math Equation,” which was released as a single following Lonesome Crowded West, give hints to the band’s development since then. The album is, therefore, a useful summary of the band’s development, a journal of their progress through their first half-decade before they moved from the indies into a larger spotlight.

The Moon and Antarctica

After two albums for Up, Modest Mouse made the jump to the majors by signing with Epic Records. This transition, along with some placements of their songs in commercials, had longtime fans worried that the band had sold out. While those fears were easily dismissed by Brock (“I like keeping the lights on in my house,” he deadpanned), it’s true that The Moon and Antarctica marks a turning point for the band. It features cleaner production due to a bigger budget and a new producer in Califone’s Brian Deck, who later played in Modest Mouse side project Ugly Casanova. Brock’s scope has expanded from the Western United States to the entire cosmos, as evident on “3rd Planet,” “Dark Center of the Universe,” and “The Stars Are Projectors.” And it’s certainly a more varied outing, with tracks like the dance-punk “Tiny Cities Made of Ashes” that would be unthinkable on earlier releases.

Still, the core features of Modest Mouse are present. Many of these songs are tighter and more constrained as if the band knows they are approaching rock radio stardom, but on tracks like “Life Like Weeds” and “The Cold Part” they still find room to show off, with the interplay between Green’s drums and Judy’s bass particularly prominent. Lyrically, too, we get all of Brock’s witticisms (“You cocked your head to shoot me down”), musings on religion (“It takes a long time but God dies too”), and daydreams of escape (“I wanna live in the city with no friends and family”).

Good News for People Who Love Bad News

Good News for People Who Love Bad News broke Modest Mouse into the mainstream on the strength of the disarmingly optimistic earworm “Float On.” It remains their most successful album and the only one to earn platinum status by selling 1.5 million copies. Still, behind the scenes, the band struggled more than ever before. Jeremiah Green had quit the band for mental health reasons, making this the only Modest Mouse album he does not appear on. The initial sessions were scrapped, and the lineup was reshuffled, as new drummer Benjamin Weikel joined and Gallucci was added full-time.

Brock, who struggled with drug and alcohol abuse, got his jaw broken in a fight outside a bar during the Moon and Antarctica recording sessions. He later did a stint in jail for a DUI. Album closer “The Good Times Are Killing Me” describes this period: “Have one more, have twenty more ‘one mores’/ And it does not relent/ The good times are killing me.” In this context, the rosy outlook of “Float On” looks more like teeth-gritting determination than real optimism, as though Brock’s mantra that “we’ll all float on” was a way of confronting his myriad personal and professional obstacles. The good news is that it worked; although the recording of Good News was a low point for Modest Mouse, its success enabled them to rebuild.

We Were Dead Before the Ship Even Sank

For Modest Mouse’s much-anticipated next act, Green rejoined the band along with a surprising new guitarist in The Smiths’ Johnny Marr. Although We Were Dead Before the Ship Even Sank ultimately sold less than half the number of copies as Good News, it was the first Modest Mouse album to climb to the top of the Billboard charts. The public’s curiosity about how they would top themselves contributed to We Were Dead’s success, but the rest of the work was done by lead single “Dashboard,” with its persistent 4/4 beat, glossy production, and horn section. Marr’s presence here is subdued—this is far from Smiths-lite, for better or worse—but his involvement in songwriting did seem to break open Brock’s formula and allow for some unusual choices. “Spitting Venom” transforms from folk rock to punk rock to post-rock across its eight minutes. “Parting of the Sensory,” one the album’s best tracks, ends with a frantic stomp-clap chant of “Someday you will die somehow and something’s gonna steal your carbon.” James Mercer also takes a guest vocal turn on three tracks here, including “Missed the Boat,” which quite appropriately verges into Shins territory in its chorus.

Strangers to Ourselves

It took eight years for Modest Mouse to record Strangers to Ourselves—eight years filled with rumors, canceled tours, delayed release dates, and much frustration. Along the way, Johnny Marr and Eric Judy left, and collaborations with Nirvana’s Krist Novoselic and Outkast’s Big Boi were sought out and then abandoned. After the breakout success of Good News and the tricky follow-up of We Were Dead, it seemed as if the band had been frozen by their success. How could Brock write without a chip on his shoulder?

When Modest Mouse’s sixth album finally arrived, it became clear that (part of) the reason for the delay was a free-roaming experimentalism that saw them stretching their sound in unaccustomed directions. While some of their experiments failed, some succeeded in surprising ways. On the bombastic six-minute groove “The Ground Walks, with Time in a Box,” the band does their best impression of Remain In Light-era Talking Heads. “The Best Room” recounts Brock’s stay at a seedy motel, with his barking vocals recycled from Good News’ “Bukowski” over clanking and clattering percussion. The title track is the closest they have ever gotten to a ballad, complete with strings. It finds them back on the road but hardly moving at all. “We’re lucky that we slept/ Didn’t seem like we realized we’d be stuck in traffic,” Brock sings, seemingly apologizing for the album’s delay by reaching for an automotive metaphor from the early days when they first started their long drive.