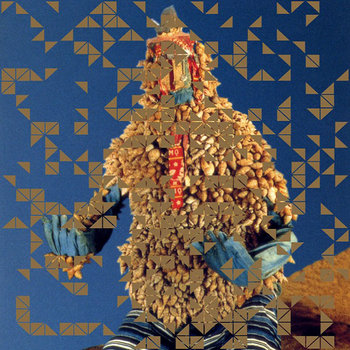

Photo by Phillippe Levy, illustration by Bandcamp.

Photo by Phillippe Levy, illustration by Bandcamp.

There’s a photo of sound artist and composer Ghédalia Tazartès, who passed away in February this year, sitting in his apartment nicknamed “L’Atelier” (“the Studio”) near Bastille in Paris. He’s astride a chair, wearing a kilt, with an accordion perched on his lap. The way he stares at the camera at first seems imperious—as if daring you to mock his get up. But a closer look suggests that maybe his stare is more knowing. He’s in on the joke.

“Humor” is the first word spoken by his daughter Élie Tazartès when asked to describe her father. Everyone who met him would likely agree. “Very sarcastic… in an old school French way” agrees Bill Kouligas, a devotee of Ghédalia’s music who released one of his albums on his label PAN.

Born into a Ladino family—the name given to the Jewish diaspora expelled from Spain in 1492—who emigrated from Thessaloniki in Greece, Ghédalia Tazartès grew up in post-war Paris. Before becoming an artist, he worked in a tire factory and even an abattoir, says his daughter Élie. Of course, this was 1968, so it wasn’t just about work. “He stopped the machines, gave grand speeches.” He soon got fired and decided to become a painter, while also beginning to experiment with music using his voice and a pair of cassette recorders.

He installed himself in the district of Aligre, just east of where the Bastille prison once stood. When he moved into his apartment in 1962, the area was a “quartier populaire” full of craftspeople and workers. It has since gentrified considerably, but retains some of its past via a well-known flea market, where artisans still sell their wares. Living and working close to this had great personal and creative significance to Ghédalia, explains Élie. “For 50 years, he went to the Marché d’Aligre every morning to chat and look around.” She considers her father’s music as sculpture. “The process of recording, assembly—it’s craftsmanship.”

His music often sounds as if it was assembled rather than composed, due to his makeshift strategies for working with tape loops (he would string them around his apartment, over furniture and around the microphone stand) and what he did with his voice. When he made use of lyrics in his work, it was always material that could be bent, dissolved, or destroyed entirely. Often, he preferred wordless chants and strange incantations. That’s maybe what makes his sound so otherworldly, suggests Quentin Rollet, a close friend and a veteran improviser who’s played saxophone for Nurse With Wound and The Red Krayola. “You think you’re somewhere else. But you can’t find anything to hold onto, because it doesn’t look like anything you know.”

“It was something very familiar to me but also something very strange and out-there” adds Kouligas. He remembers his late friend telling him that there was one loop that recurs on every one of his records, often on multiple tracks. “‘It’s my comfort zone,’” Kouligas remembers him saying, “‘I need to have it before I can enter the music.’” Combining such a personal approach with a garden-shed approximation of composition makes his work charming—never precious or pompous. Like the man, the music is generous, funny, and warm, says Kouligas.

“Artisanal and a bit punk, in the best sense of the word,” says Laurent Gérard, describing the methodology behind Ghédalia’s work. Gérard records as Èlg, and formed Reines d’Angleterre with Ghédalia and his friend and collaborator Jo Tanz in 2008. Ghédalia’s improvised strategies stood in sharp contrast to the rigid formalism of French musique concrète in the 1970s and ‘80s. Unlike much of the arch, academic experiments of the INA GRM and the IRCAM—François Bayle was apparently dismissive of an early performance—Ghédalia’s music is workmanlike, handmade. It “smells of sweat” says Gérard. “There’s something erotic… something spiritual.”

Beyond that, there was the humor. Sometimes it was direct: There were the absurdist track titles (“The legendary life and death of the spermatozoid Humuch Lardy,” “The crab never plays with dolls”) and crude, coarse stand-up routines delivered mid-album (“Dix” on Ante-Mortem—and if you speak French, consider yourself forewarned). Or it could be more subtle, a collision of two unexpected elements. On Voyage À L’Ombre he sings while laughing at the same time. Moments like this make it clear he intends to entertain rather than impress or shock. His music, says Gérard, is light, “like gas. It floats in the air.”

This spirit could express itself in other rare and sublime ways too. Laurent remembers that during one evening of heavy drinking, Ghédalia put on an Èlg record, stood up on a table and began to recite poems by Rimbaud over the top, “with an astonishing power of elocution and embodiment.” After 20 minutes, he cut the music and sat back down, leaving the room speechless. Laurent shakes his head in disbelief even remembering it. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone else manage to do that, without it being ridiculous.” He also pays tribute to his former bandmate’s remarkable ear and fertile imagination. “I said to myself, if at 60 I’m like him, that’s great.”

As a collaborator, Ghédalia receives the highest praise. Minimalist composer and no waver, Rhys Chatham, who first met him in New York in the ‘70s at CBGBs (Chatham remembers Ghédalia yelling at him from the audience—a vision of the irate Frenchman in New York). The two would collaborate for a pair of concerts. The first one took place in the garden of their shared agent, Pascal Régis, in 2018. “It was just the perfect collaboration, where nothing had to be said,” Chatham says, smiling at the memory. “It was like playing with Prandit Pran Nath [The Indian classical musician who taught Chatham, as well as La Monte Young, Terry Riley, and John Hassell]. He would start with a seam and develop something that was very raga-like without being raga at all.” More performances were intended to follow, and a recording of the second concert is due to be released on Belgian label Sub Rosa later this year.

Chatham also remembers Ghédalia’s apartment, a “time capsule” filled with Ghédalia’s sculptures, installations, and trinkets that he’d collected, principally from the Marché d’Aligre. A book of photos taken by Ghédalia was published by Bisou Records a few weeks after Ghédalia’s death. Pascal Régis remembers it as a place where time and space seemed to stand still. “I often said to myself that it must look like [writer and founder of surrealism] André Breton’s apartment, or someone like that.” The first time he visited, there was a pigeon loose in the room, and it took him a while to realize that it was Ghédalia’s pet. “He kept it in a cage, but he didn’t want to shut the door. So from time to time, it would fly across the room.”

Ah yes, the pigeons. Élie remembers her father teaching her about his beloved pigeons. “The greatest telenovela in the world,” she says. “So many stories of love and betrayal.” It was part of his unique way of looking at the world—being able to turn the maligned bird into an object of love and entertainment.

Here are six records from his long discography that reveal a little more about Ghédalia Tazartès’ unique perspectives.

Diasporas

Diasporas is where it all began, with Ghédalia’s debut 1979 LP becoming a cult classic that has been reissued twice (in 2011 and 2020, both times by Dais Records). From the cold vocal open—“the way it starts suddenly with his singing is just fantasticm” says Pascal Régis—it’s still like nothing else that has ever been made. It sounds how the Centre Pompidou looks, composition turned inside out, the infrastructure exposed and the vital organs laid bare. Yet it would be impossible to replicate, even if anyone knew how it was made. “No-one else could make Ghédalia’s music,” says Élie Tazartès. In truth, Ghédalia’s compositional style changed only marginally over the years, even while he added new elements, sounds, and technology. It’s probably why this record remains the favorite of many of his fans and collaborators. When the blueprint is this astounding, there’s no need to change too much.

Granny Awards

“There are track names that make me roar with laughter, so I like those a lot,” says Quentin Rollet. Opening track “Ferme ta gueule, Zarathoustra!” (“Shut your mouth, Zarasthustra!”) is not only one of Ghédalia’s funniest track titles, but also one of a few that features the gurgling and burbling of a future politician. The sampled loop of a child at the start of the 17-minute suite—which unfurls through birdsong, stuttering tape chatter, and heady incantations—is none other than the infant voice of Raphaël Glucksmann, a former journalist and now likely the only European Member of Parliament to have featured on multiple albums of experimental music. The tracks on Granny Awards were assembled and recorded in the ‘80s, but the source material dates back to the ‘70s, when Ghédalia, a young father himself, used to babysit for his friend, the philosopher André Glucksmann. The ‘70s loom large over the second side of the record as well: there’s a sneering, bratty tribute to his punk heroes on “Wild.”

Voyage à l’Ombre

When I ask Élie Tazartès what her favorite Ghédalia record is, she names Voyage À L’Ombre almost without hesitation. “But it’s not because I’m on the cover,” she assures me. “It’s full of tracks that have plenty of memories for me.” Bill Kouligas also picks part six of the opening 14-minute track as a perfect example of Ghédalia’s spirit: “humorous, direct, mystical, odd, trippy, traditional, and very contemporary at the same time.” Some of the source material for the record, released in 1997 on admirer and collaborator David Fenech’s label Demosaurus, came from a trip Ghédalia took to Kerala in India, with a young Élie along for the ride. While working with choreographer Annette Leday and Kerakahli dancers, he found time to make field recordings, including one of the octogenarian singer whose voice provides the primary loop for “Transmalabar.” It’s also one of only two records that Ghédalia would release during the ‘90s when he drifted away from releasing and performing music and focused on composing for theatre and dance. Perhaps that explains the sense of relative restraint on what is one of Ghédalia’s longest recordings.

Reines d’Angleterre

Les Comores

Reines d’Angleterre were formed over drinks in Ghédalia’s apartment by Laurent Gérard (Èlg) and Jo Tanz (Fusiller), who play together as Opéra Mort and had come to know Ghédalia through experimental shows at Les Instants Chavirés in Montreuil on the outskirts of Paris. Gérard’s friend Dylan Nyoukis had been asking him to persuade Ghédalia, who hadn’t performed live in nearly 20 years, to come and play his Colour Out Of Space festival in Brighton in 2008. To the surprise of Gérard and Tanz, after some cajoling, Ghédalia agreed but on one condition: That the two 28-year-old musicians form a group with him. The only problem was that the festival was in three weeks. But Ghédalia was adamant, remembers Gérard, “He said ’It’s that or nothing!’” The trio would play nearly 20 concerts over the next two years, and release two albums for folk and avant-garde label Bo’Weavil. Their first effort, Les Comores, is a set of raw live recordings that Gérard calls “a bunch of morons making art brut.” Though his bandmate might have had other ideas: Gérard remembers the two nearly came to blows in the airport at Montréal when Ghédalia insisted for over an hour that Reines d’Angleterre were a free jazz group. Whatever the genre, the music is worth hearing. Come for the menacing hum of throat singing and eerie electronics; stay to hear Ghédalia cuss out and then admit to killing the imaginary “hijo de puta” who’s slept with his wife. What else would you expect from three musicians calling themselves the Queens of England?

Repas Froid

Repas Froid (“Cold Meal”) began life as a release on Jo Tanz’s DIY label Tanzprocesz, which releases underground noise and oddities on cassette and CD. The name comes from the nature of the material: 20 individual short tracks that Ghédalia had recorded in L’Atelier and used as a backing tape when he played live in the 1970s, adding vocal and percussive improvisations over the top. (He would continue this practice when he started performing solo again after 2009, turning up to gigs with a CD, a Tibetan singing bowl and odd percussive trinkets). Around 2010, Jo Tanz contacted Bill Kouligas saying that Ghédalia wanted to rework the material into two long pieces, and asked if PAN would be interested in reissuing it. “I said that I would be honored,” remembers Kouligas. Ghédalia didn’t have an agent or even a computer then, “so he was sending us hand-written letters, which I still have today.” Ghédalia’s music fit the label’s aesthetic perfectly, but Kouligas still isn’t sure what the musician thought of the rest of PAN’s roster. “I once sent him a big box of records as a thank you, because he actually sent me some of his—I was missing some original records.” The next time the pair met, he remembers Ghédalia’s response as short, and a little cryptic “You have a very interesting label, there are a lot of things I don’t understand. There are a lot of things I very much enjoyed.” Regardless of musical tastes, the pair were fast friends, and when Kouligas was packing up to move house, he re-discovered a signed copy of Repas Froid that Ghédalia had gifted him. “My Bill, so kind and elegant,” read the inscription, “I can never thank you enough for your welcome, this record, your presence. I love you. Ghédalia T.”

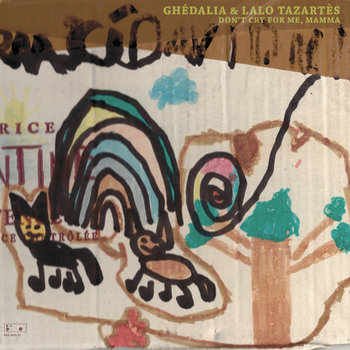

La Bar Mitzvah du Chien

Vinyl LP

Tazartès’ abrupt sense of humor could even catch his closest friends off-guard. Quentin Rollet remembers one particular moment during the production process of La Bar Mitzvah du Chien, a record that he released on his label Bisou Records, in 2015. “He said to me, ‘I want the cover to be a naked, bearded man, on all fours like a dog.’” Rollet said he thought it was a great idea. “Then he then told me ‘I want it to be you.’” From that point on, there was no question as to what the cover would be. “It’s a beautiful photo, I’m not ashamed,” says Rollet, even though the image seems to follow him to every record shop that he visits. The record itself, like many of Ghédalia’s works, was based on compositions he initially recorded in the ‘90s for theatre, as Rollet only discovered recently. Ghédalia loved to recycle and re-use old tapes and pieces of work—nothing ever seemed to be finished. And this went beyond his music. His apartment and the sculptures he filled it with were in a state of “in perpetual construction,” says his daughter Élie, “things that changed place, were taken apart, reconstructed elsewhere.” Le Bar Mitzvah Du Chien is remarkable for another reason. Whilst listening back to the test pressings, Ghédalia began to tell Rollet the story behind each track. Rollet convinced him to repeat the performance for the camera, and they recorded a series of short videos, helpfully subtitled in English, to accompany the release. They’re a unique insight into his thoughts and sense of humor—watch for the moment when he describes “the sea attracting a harpsichord to the shore.”